A “Bad Girl” on the Campaign for a Safe Abortion

“Only bad girls get abortions.”

That’s what my boss, the deputy administrator in charge of all New York City’s health bureaus and hospitals, told me 50 years ago, when I urged the agency to advocate for the groundbreaking abortion repeal bill pending in the New York State legislature.

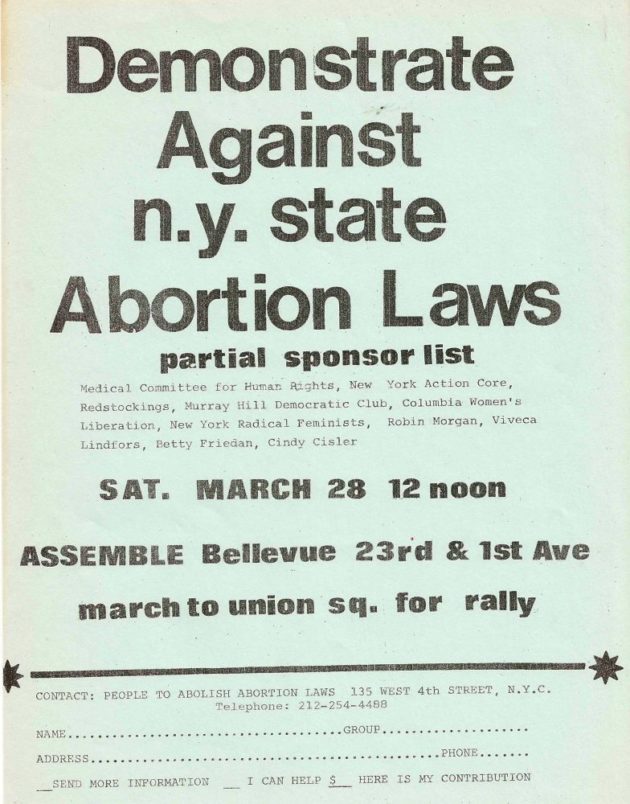

According to the statute then in effect, abortion was allowed only to save a woman’s life. The repeal bill decriminalized this 130-year-old law, permitting abortion up to the 24th week of pregnancy for any reason, and after that, if the mother’s life was at risk. But despite vigorous support from women’s liberation groups, the National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL), and concerned clergy, hopes for its passage remained low. Similar repeal bills had failed repeatedly throughout the 1960s.

At the time, I was the youngest person and only female on the executive staff of the Health Services Administration, the “super” agency consisting of the departments of Health, Hospitals, Mental Health, and Prisons. I reported to Gordon Chase, the HSA chief appointed by Mayor John Lindsay, and to Jim Haughton, deputy administrator.

Believing that HSA had an opportunity to influence the vote upstate, I sent a barrage of memos urging my bosses to put together information about the city’s abysmal experience with illegal abortion. But although both Chase and Haughton were caring executives, they did not consider abortion to be either a major health policy issue or a matter of social justice. They told me that the agency must concentrate on important matters such as drug treatment and lead poisoning. There were many more vital matters to deal with than women’s unwanted pregnancies.

Besides, as Jim had said, “only bad girls get abortions.” Provoked by this comment, I blurted out a long-kept secret: “I had an abortion.” It had been a frightening back-alley procedure, with a drug-addicted doctor and cockroaches scuttling on the floor. The memory still haunted me. My admission startled Jim; I did not fit his preconceived category of young women who had abortions. But in personalizing the issue in this way, it helped humanize it. Jim and Gordon gave me the green light to craft an agency position in support of the repeal law for Mayor Lindsay and the state legislature.

Provoked by this comment, I blurted out a long-kept secret: “I had an abortion.”

Helped by a powerful, impromptu network of women, I put together the statements. From the long-time head of the Health Department’s division of maternal services, Jean Pakter, came statistics that showed that hundreds of women were dying from causes related to abortion. I incorporated this data in our statement, which we sent to the Mayor through his Special Assistant, Ronnie Eldridge. Eldridge and allies, including the Mayor’s pro-choice wife and sister-in-law, encouraged Lindsay to support the bill. The Mayor did so, declaring that abortion needed to be removed from the penal code because too many women were needlessly dying.

Upstate the struggle was intense. On April 9, 1970, after its passage in the New York State Senate, the bill passed the Assembly dramatically by a single vote when George Michaels, a Democrat from a heavily Catholic district, broke the tie, reversing his previous vote. He revealed that at first he had gone along with the Democratic Party, but after his daughter-in-law convinced him that thousands of women would be harmed if the bill failed, he re-cast his vote. When the Democrats refused to endorse him in the next election, Michaels ran as an independent, but lost his seat to an anti-abortion challenger. Decades later, the Kennedy Foundation gave Michaels a Profile in Courage Award. Signing the legislation at the time, Governor Nelson Rockefeller stated that the credit should go to “women’s liberation” and the “wives of the Senate and the Assembly” who put the bill through.

With the repeal of the law, New York changed history. It became the second state (after Hawaii) to provide abortions to pregnant women through their second trimester, but the first that did not require state residency. The law went into effect on July 1, 1970. As part of my job, I visited municipal hospitals to assess their compliance, pretending to be pregnant and wanting an abortion. There were many kinks in the system, but most were eventually ironed out. The state’s broad experience in providing safe and legal abortions served as a precedent for Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationally two and a half years later. More than 350,000 women came to New York for abortions over that period.

A chain of advocates had helped to secure the success of abortion legalization in New York and then nationally. Their personal testimonies, petitions, and briefs became building blocks for the far-reaching changes that took place. Those who whispered in the ears of decision makers were critical pieces of the puzzle. These back-channel influencers are usually left out of the historical record, but they, too, shaped history. Let us give credit to the lawmakers and officials, but also to the wives, sisters, daughters-in-law, friends and other activists, whose courage and empathy around the difficult issue of abortion helped to empower women. With Roe v Wade in jeopardy and states’ imposing increasing restrictions on abortion access, the actions of this army of women, and their male allies, show the power of committed, passionate advocacy.

Joyce Antler is the author of Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement, and Professor of American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Emerita, Brandeis University.