Present Perfect: a Pandemic Bar Mitzvah

Hunched over my computer screen, I hear my son’s halting Hebrew rhythms mingle with my father’s smooth baritone. This is pandemic bar-mitzvah prep: Sammy chanting into a screen in one room of my house while I host a university class in another. Sammy practices like this all Spring with his grandfather three states away. I have no idea whether we will be able to celebrate together when his September date comes, or what that celebration might look like.

Before Covid-19 hit New York, Sammy was a regular on the tween party circuit. Most weekends he would return home disheveled and sweaty, on the wrong end of a sugar high. Every corner of his bedroom was littered with his friends’ bar-mitzvah swag—sweatshirts, sports jerseys, hats, towels, sometimes all of the above—emblazoned with a version of the celebrant’s name, whether in the colors of a sports team or in homage to a high fashion brand. Somewhere along the line, the logo had become a central part of this rite of passage, updating the ancient ritual as both distinctly individual and firmly rooted in American popular culture.

Technically speaking, a bar or bat-mitzvah is not something you host, but a milestone you mark: the day that a child becomes obligated to participate fully in Jewish life. It really is a rite of passage— a recognition of movement forward in time. We celebrate so as not to miss the preciousness of that moment. But in many American Jewish communities, there is pressure to host a large affair. As these celebrations have grown in size and scope, they can obscure the very thing they are meant to celebrate.

When it came time for our two older daughters, we tried our best to focus on the central religious ceremony. Still, there were guest lists to coordinate, caterers and florists to speak to, clothing to purchase. After months of preparation, the celebrations—joyous as they were—flew by in a whirlwind. If there was a moment we were meant to mark, I worried I’d missed it.

Just as we were preparing for our last go-round, Covid 19 hit New York, seeding itself not far from our own Westchester-adjacent community. By April it became clear that planning for Sammy’s bar-mitzvah would have to be put on pause. Our synagogue sat empty. Time had stopped moving in predictable ways. We would have no choice but to do things differently.

As we adjusted our expectations, we found ourselves thinking about what we really wanted. We were newly aware—in the midst of lockdowns and restrictions—of what we could control and what we could not. The age-old words of Jewish grandparents, “as long as you have your health!” took on new meaning. Just being together felt like more than enough.

Meanwhile, Sammy practiced his Torah portion with my father over Face Time (that pre-Zoom relic!). My father had prepared Sammy’s sisters and cousins remotely as well. Through weekly meetings, he came to know each of them not just as grandchildren but as students, and he catered his sessions to their different personalities. He debated textual interpretations with Abby, our budding intellectual; with musical Eliza, the notes of the Torah came so quickly that he kept adding additional portions for her to chant. Sammy, his first grandson, was the only member of the family who could match my father’s sports knowledge, and they kicked off each session by discussing whatever it is that sports’ fans discuss. This, at least, did not have to change.

By June, we knew we had to broach the subject with Sammy, who was spending the summer not at sleepaway camp with his friends, but in his bedroom. With some trepidation, we asked whether he would be disappointed if only close family would get to hear him after all these months, and not the hundreds he had been imagining.

“Are you kidding?” he responded. “That would be awesome.” Our easygoing third child had gone along with what we had done for his sisters, but it wasn’t a plan he had chosen.

Faced with Sammy’s palpable relief, I realized I was feeling much the same. The pandemic had released us from expectations that weren’t really ours in the first place. What’s more, I found myself excited for what was emerging: the bar-mitzvah as a small, special experience that would be uniquely his.

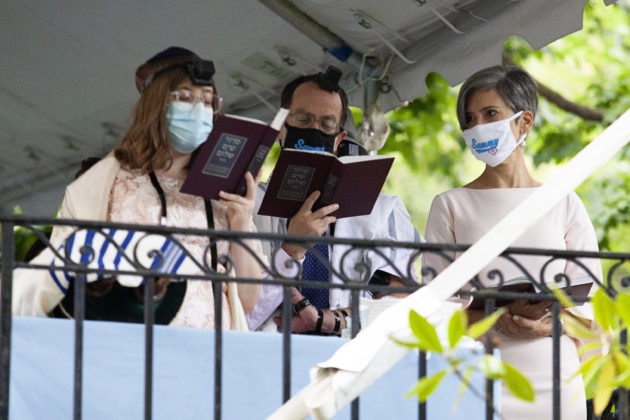

And so, on a humid Thursday in early September, local aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents gathered for a twenty-person service under a tent stretched across our front porch. For a few hours, we created a bubble of joy under that canopy, tuning out the pandemic fears.

Sammy read from a Torah borrowed from the synagogue, his new prayer shawl sliding off broadening shoulders. My father watched from a safe distance, kvelling. My husband choked up just as he expected to, and when the neighbor’s lawnmower began to roar while Sammy was speaking, we laughed, since we knew the speech by heart already. Abby and Eliza had helped him practice, coaching him to be ten times slower and to picture everyone in their underwear. We threw candy, and then we ate brunch around tables decorated with last-minute flower arrangements and bottles of Purell. The bar-mitzvah logo that Sammy had selected pre-pandemic—his name in old-timey baseball lettering against a pink baseball diamond—ended up on the face masks that we wore as we hugged our relatives carefully and from the side.

At some point, I realized I didn’t have to remind myself to be present. Being present was natural because it was all we had been able to do for months, when it was impossible to imagine what the next day or week would bring. That state of being was both repetitive and exhausting until the bar-mitzvah itself. Without an endless stream of guests to entertain, we could focus on each other. Sitting together on the porch of the home where we had spent months sheltering from the virus, we were closer than we had ever been—a family unit if there ever was. Among so many other life lessons, the pandemic had prepared us for this.

The present perfect is a grammatical term referring to an action begun in the past that continues into the present. It’s a good way to think about what a bar mitzvah should be, as a ritual that joins the now with the then. In modern America, we create this temporal bridge any number of ways: with logos, or a deejayed dance party. But in 2020, we discovered that we didn’t need help to accomplish the time travel. For the few hours when we stopped mid-pandemic to celebrate, we found ourselves within this rite of passage like never before. We were able to experience the moment in exquisite stillness. We were present, and it was perfect.