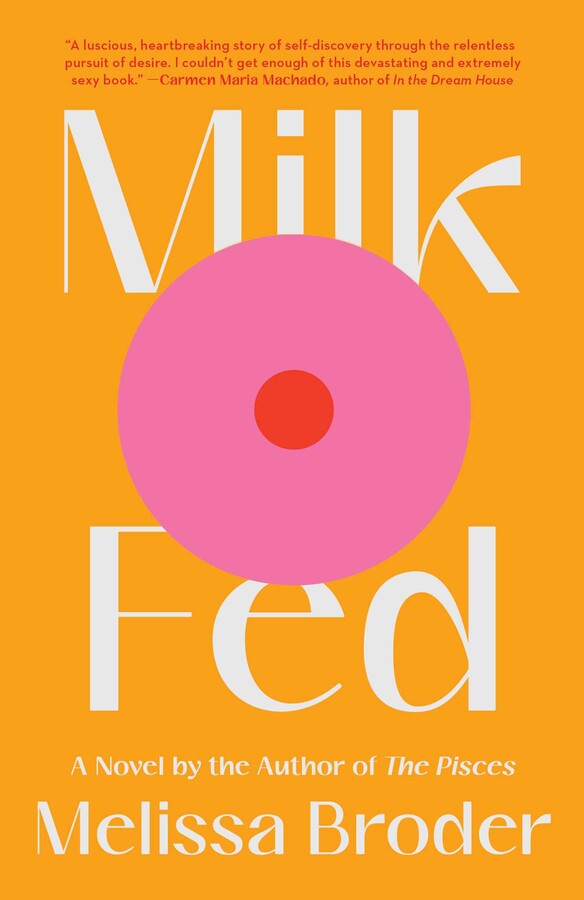

“Milk Fed:” A Tuna-Flavored Take on Sex, Life & Fiction

I’ve long related to Melissa Broder’s musings on tuna salad. The “salad” part, as she points out, adds to the embarrassment one feels when ordering at a deli. From her popular twitter account @sosadtoday, Broder tweeted, “The seventh wave of feminism is a moist tuna salad sandwich ingested on public transport.”

Let it be known that I have eaten a tuna salad sandwich on an everything bagel during rush hour on the subway. Broder allowed me to think of this act as feminist. In her podcast “Eating Alone in my Car,” she gives a literary framing for her conceit of tuna salad as a symbol of marginality and unassimilated Jewishness:

I identify at my core level as a tuna salad sandwich. Philip Roth, may he rest in peace—in [his novella] Goodbye, Columbus, the narrator is from a poor, Newark, mayonaisy, tuna salady, white fish salady Jewish family. He’s in love with this girl Brenda who is from a nouveau-riche, more Americanized, nose-jobbed, Jewish family. And they’re more like fresh fruit. They eat fresh fruit. More clean. Less fattening. Deep down, I’m not fresh fruit. I’m a tuna fish salad sandwich.

Broder’s latest novel, Milk Fed, is a reclaiming of tuna salad identity. If tuna is obtrusively smelly, ethnically distinct, and unsexy, in Milk Fed, Broder gives it an overt and lively sexuality.

While reading, I thought, “I, too am tuna salad at my core.” Throughout my life, I’ve understood my desirability as in conflict with my tuna salad core. Milk Fed’s raunchy, explicit sex scenes skirt the line between earnest and satirical, ultimately asking the reader to reconsider if the attributes you view as most grotesque are actually your sexiest. Milk Fed is an exorcism of shame; a fantasy of overcoming internalized sexism, homophobia, and anti-Semitism through the pursuit of earthly pleasures.

The narrator of Milk Fed is Rachel, a 24-year-old secular Jew who works an unfulfilling office job at a LA talent management agency. She has a history of anorexia and an ongoing disordered relationship with food. Rachel suffers from low self-esteem and persistent, low-grade depression. As Audre Lorde wrote, “The severe abstinence of the ascetic becomes the ruling obsession. And it is one not of self- discipline but of self-abnegation.” The opening chapters of the novel describe, in somewhat triggering detail, the obsessive, punitive daily eating rituals Rachel observes in order to remain thin: nicotine gum breakfasts, dressing-less salad and diet frozen yogurt for lunch. While reading these chapters I couldn’t help but anxiously compare my own eating habits.

Rachel meets Miriam, an Orthodox Jewish woman of the same age who works at her favorite yogurt store, Yo!Good. There is an implicit class difference between Miriam and Rachel. “The reform synagogue I’d attended growing up in Short Hills New Jersey, was way more Chanel bag Jew than Torah Jewish.” Miriam is a Torah Jew—the inverse of slim, assimilated Brenda Patimkin, the love interest in Goodbye, Columbus. While Brenda is reserved, worldly, and Radcliffe educated, Miriam is sheltered and naïve with a rebellious streak. Rachel notes how “her innocence still radiated.” Dressed in modest, long dresses, Miriam smokes clove cigarettes—a charmingly garish choice—outside the yogurt shop and tells Rachel, “I love to drink. Mai Tais.”

Though Miriam is blonde and pale she has “a shtetl essence that perhaps only a fellow Jewish could detect.” And most importantly, she is “undeniably fat, irrefutably fat” with enormous, fabric-stretching breasts. Rachel observes “it was as though she didn’t know or care that she was fat.” Miriam’s unassimilated Jewishness, and her obliviousness to her size–signs of unassimilated nonconformity–are the attributes that Rachel finds increasingly compelling. Her sexual desire grows as Miriam coerces her into eating elaborate full-fat frozen yogurt sundaes. As Rachel indulges, breaking her usually “spartan regimen,” she begins to question her desperate need to control her appetite. “She exceeded my worst fears for my own body,” Rachel notes of Miriam. Yet in her fantasies, she tells us “I longed to feel her big belly against mine.”

As Rachel falls in love with Miriam, she delights in the aspects of lowbrow orthodox Jewish culture that I have often denigrated or felt ashamed of. In an event that marks the beginning of Rachel’s journey of self-actualization, Miriam takes her to a Kosher Chinese restaurant in Pico where the two get drunk on sugary, tropical cocktails and finish a pupu platter intended for four to eight people. Rachel drunkenly looks around the restaurant and observes a table of Chasidic men sharing noodles. “I liked their talking. I liked their noodles. I could hear music playing on a speaker overhead. The music sounded beautiful to me…I laughed when I realized it was an instrumental pan flute version of Santana’s ‘Smooth.’” Whatever is commonly viewed as crass and unrefined becomes a point of hidden beauty.

As someone who was raised Modern Orthodox, the experience of reading Milk Fed was both uncomfortably familiar and cathartic. Broder’s descriptions of kosher food: “sweet-and-sour meatballs with raisins in the sauce, and challah with margarine,” remind me of the foods I have rejected both for their caloric density and culinary inferiority. So too, Broder’s descriptions of Miriam’s body remind of the parts of my own I dislike.

When Rachel makes love to Miriam, she describes her breasts: “magnificent, weighty pendulums…beneath her areolae were a network of veins, blue and purple, bringing forth the blood that sustained her.” Miriam’s pubic hair is “soft shtetl wool.” When I examine my body in the mirror, the attributes I regularly take issue with are uncoincidentally the ones I associate with my own shtetl lineage: heavy breasts and pale, nearly translucent skin that reveals blue veins. Growing up, I heard other Ashkenazi women make generalizations about our bodies: “Jewish women age badly.” I thought of this often in the dressing rooms at specialty bra shops on the Upper West Side where, surrounded by other Jewish women, I was fitted for thick-strapped, matronly bras. I have always taken secret pleasure in hearing that I do not look Jewish because I am light-eyed and blonde. The discomfort that surfaces while reading Milk Fed is my own grappling with self-hatred.

Towards the beginning of the novel, Rachel’s therapist asks her to sculpt an image of herself out of playdough. The figure is fleshy and amorphous. “I think she’s worthy of love,” the therapist says. Though the therapist’s language is buzzy and trite, we understand her message as true. Broder asks us to expand our conception of what and who is worthy of love and admiration. Tuna salad, for example. Whitefish salad, creamed herring—all foods and identity associated are worthy of our love. During sex with Miriam, Rachel tells us, “I smelled the faintest waft of shit coming up from underneath her. It smelled like heaven…it smelled good because it was her.”