When Should a Classic Book Become a Relic of the Past?

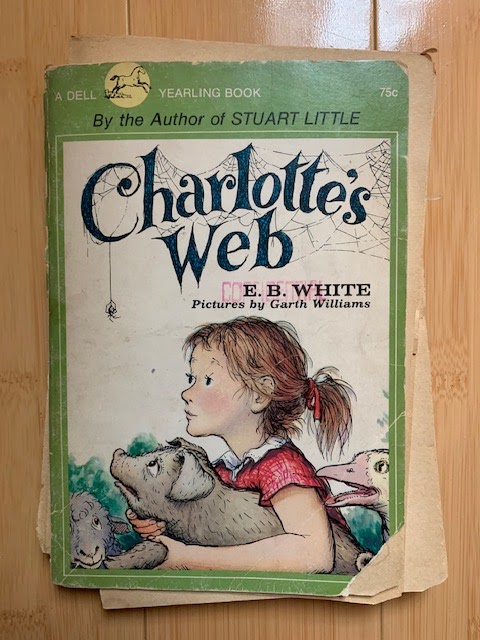

It’s bedtime. In the cramped bottom bunk, I sit with one child tucked under each arm, a yellowing copy of Charlotte’s Web in my hands. It belonged to my mother as a child, and as I approach my mid-twenties, it has been more than a decade since I’ve read it myself. As a babysitter, I love the opportunity to revisit and share with “my” kids the books I loved as a child.

I begin reading, and barely make it two pages before I start to feel uneasy. In case you don’t have its exposition committed to memory, the story begins with the birth of a litter of pigs on a small family farm. Mr. Arable (the protagonist’s father) is preparing to “do away” with the weakest piglet, because it would require extra care to survive. Naturally, Fern cries, begging her father not to kill the pig, to which he replies, “You will have to learn to control yourself.” Control yourself? Isn’t that one of those phrases men used to patronizingly say to “hysterical” women? The feminist childcare worker in me winces. Because the “hysterical” woman stereotype has deep roots in the infantilization of women and the notion that we are emotionally “unhinged”—which is not only an insult to a woman’s expression of real, reasonable feelings, but also to the feelings of a child. Mr. Arable feels that his daughter has lost control because she is showing pain at the idea of her father killing a baby animal—I don’t know about you, but I would cry too. Of course, we readers are supposed to identify with Fern, not her father, but can my sleepy charges see through this dated family structure or will I have to keep explaining?

Looking at children’s literature through a contemporary lens is a hot topic these days. While E.B. White’s intentions seem quite pure, we also consider the many authors who do not hold up under scrutiny. Recently, we’ve seen six of Dr. Seuss’ books pulled from shelves–by his own estate–for racist drawings, drawing fire from conservatives. A few months before, we re-discovered Roald Dahl’s strong antisemitic inclinations. Before that, we took up arms as J.K. Rowling broadcasted blatant transphobia online. The big question we now ask ourselves is: Do we stop reading their books?

I continue reading, knowing that the premise of the story depends on Fern (spoiler alert) convincing her father not to kill the piglet. Just a page later though, my stomach twists again. Fern continues to (more calmly) plead her case, and as Mr. Arable considers her plea, “a queer look” comes over his face. Oy. I manage to catch myself in time to switch “queer” to “strange.” Because that’s what E.B. White meant, right? Of course, it’s common to find this use of the word in older books—I don’t blame White for using a word that had yet to take on the homophobic meaning it soon would. But as a queer woman today, it stings to be reminded that a word I (proudly) use to describe my identity originally held such a negative connotation—and now does not feel like the right time to have this conversation with two children who have never known the word to mean anything other than rainbows and television makeovers (yes, they watch Queer Eye). So, this is strike two.

Strike three comes just a few paragraphs later. In walks big brother, Avery, wielding “an air rifle in one hand, a wooden dagger in the other.” He speaks harshly, calling Fern’s piglet “miserable,” before leaving to wait for the school bus, gun still in hand. Now, I have no ill will toward Avery for his behavior—this is how he’s been conditioned to act. But it’s concerning to think that the millions of young children who have read and will read this wildly popular book may see Avery as a model for how a boy is supposed to act, whether they like it or not—all rough and tumble, no sensitivity, even toward a helpless newborn animal.

Meanwhile, Fern feeds a bottle to her new “baby.” The gender role juxtaposition could not be clearer. Like Avery, Fern becomes a symbol, and her actions set an example—while boys are stoic and play with guns, girls are sensitive and take care of babies.

Now this sends me on a feminist tangent in my head–even as I’m reading out loud. I’m all for girls embracing traditionally feminine activities, if it’s what they truly enjoy—and it seems that Fern does. My mother ingrained in me the idea that it’s a feminst act to freely embrace such activities, as it maintains their value. But today, in a misguided attempt at women’s liberation, instead of celebrating and lifting up these activities and behaviors, girls are often encouraged to act “like boys.” They receive praise for athleticism, tenacity, and not caring what they look like. The girls who play with boys and prefer soccer to ballet are cool—we tell them that they’re strong and take them more seriously for their rejection of gender norms. But this isn’t progress—it’s just change. It’s not an abandonment of oppression, but of femininity.

And don’t get me started on boys. While many of us have dramatically shifted our attitudes toward girls, we haven’t been so quick to praise the boys who embrace traditionally feminine interests and qualities—we’re getting there, but we have a lot of work to do. And of course, this all lies within the confines of the gender binary, outside of which, there’s still very little room at all.

Ironically, not only do we fail to attribute value and legitimacy to femininity, but we encourage qualities of toxic masculinity in girls—instead of telling boys that it’s okay to cry, we tell girls not to be so sensitive. Like Fern’s dad.

This is where I give up on storytime. I realize that continuing to read aloud would require either an exhausting amount of on-the-spot censorship or some very serious conversations with two young children who aren’t mine. So, we call it a night, for now.

To be clear, I do not wish to see Charlotte’s Web banished from libraries and classroom. The heart of the story is undeniably good. It’s about compassion. There is a reason why Fern is the protagonist, why her father relents to her pleas to save Wilbur, and why we find much of Avery and Mr. Arable’s behavior distasteful. White does not condone aggression, stoicism, or sexism—on the contrary, he seeks to reveal their dangers and highlight the value of kindness and empathy. Depiction of harmful behavior can be a powerful teaching tool. But all the good lessons happen in a world that is so relentlessly gendered in such a dated way. On their own, kids may miss the tonal nuances. And what seven-year-old considers an author’s intentions, especially in the opening pages of a book? These are concepts we can and should teach kids, but we cannot assume that every child has been or will be taught a sufficient level of media literacy.

So where do we go from here? For me, it’s a mixed bag. Roald Dahl’s stories—The BFG, Matilda, and Fantastic Mr. Fox, in particular—remain some of my all-time favorites. And I still have my childhood copies of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Six by Seuss. I’m not ready to fully let them go. But I’m not inclined to blindly support their authors, either. The best conclusion I can offer is, let’s teach kids how to read them. Perhaps we’ve been presented with an opportunity—teaching critical thinking to children can seem like a daunting task, but this is a great place to start the conversation. Just, maybe not at bedtime.

Arielle Silver-Willner is a Brooklyn-based writer and Editorial Assistant at Lilith Magazine. She’s currently trying to finish her first novel and works part-time in childcare.