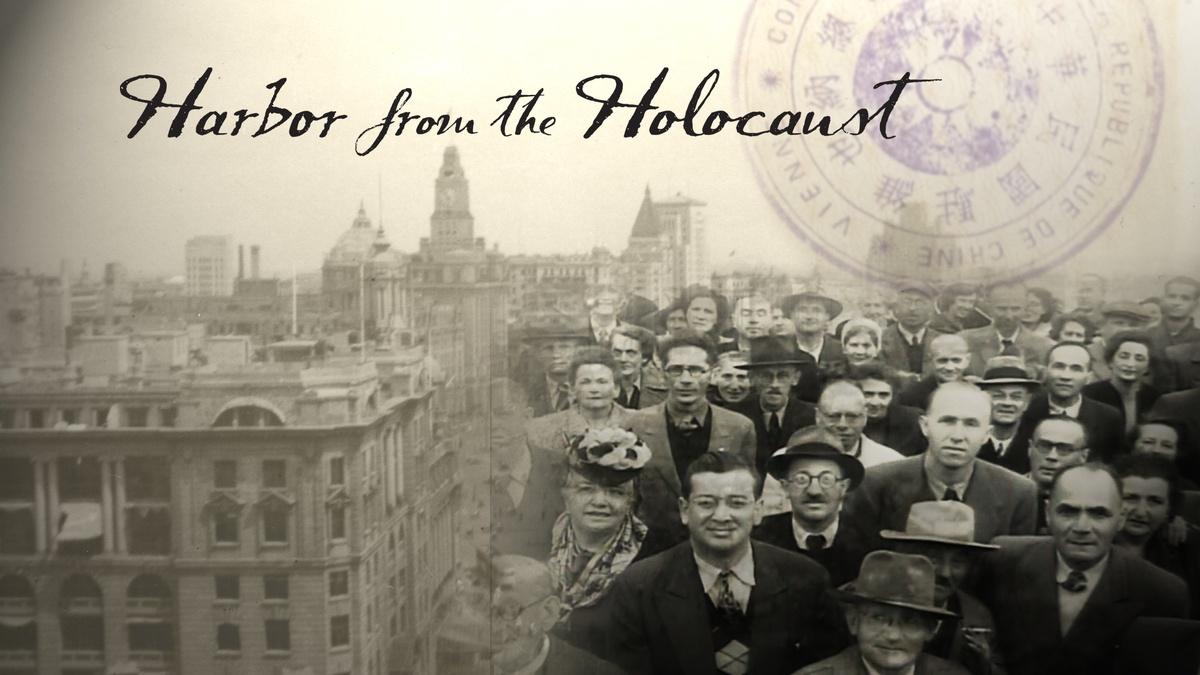

Harbor From the Holocaust: The Jews of Shanghai

By Aileen Jacobson

In 1941, Laura Margolis, the American Joint Distribution Committee’s first female field agent, was sent to Shanghai to help the nearly 20,000 Jews who had fled there to escape Nazi Germany’s persecution. In an audacious move, she negotiated with the Japanese officials who controlled Shanghai and was able to secure funds (partly from Russian Jews and other communities who had found shelter in China in previous generations) to build a hospital and expand a soup kitchen. She saw to it that the neediest refugees got at least one meal a day to keep after they were forced, in 1943, into a mile-square area known as the “Shanghai ghetto.” The thousands of Chinese people who already lived there stayed.

“Magic doesn’t come by itself,” said Violet Du Feng of Margolis’s work, which some may have viewed as a miracle. “She was the right person at the right time, and she stepped up to do the right thing. It took courage for a Jewish woman to meet with the Japanese. She risked her life. But she helped these people survive.”

Feng is the director of “Harbor from the Holocaust,” a new documentary that premiered on PBS stations September 8 and can be watched online at www.pbs.org/show/harbor-holocaust/ or www.wqed.org/harborfromtheholocaust. Margolis went on to a long career establishing programs—for children, the elderly, the sick, concentration camp survivors, immigrants–during and after the war in Europe and later in Palestine/Israel. She died in 1997 at age 93.

Even though Feng already knew about the Jews who had escaped to Shanghai, she learned a lot more about them after getting the assignment to direct “Harbor from the Holocaust.” The kindness that prevailed between the European refugees, and their Chinese neighbors who were often even poorer, emerged in her interviews. It became a dominant theme of the documentary and a tie-in to contemporary concerns. But Feng, who grew up in Shanghai and now lives in Manhattan, also noticed that she kept encountering intrepid, resilient Jewish women with powerful impacts on the Jewish community.

The former refugees featured in her film—children or adolescents then, 70 years older now—also lauded Lucie Hartwich, the smart and devoted principal of the Jewish Youth Federation of Shanghai, popularly called the Kadoorie School, after Horace Kadoorie, a wealthy Jewish resident of China. The students, mostly from Germany and Austria, got a first-rate education there. Graduates were prepared for any top university.

“Lucie Hartwich was a tough lady,” Feng said. “She forced all the children to learn English, basically to give them a future. She wasn’t running a feel-good daycare center. She gave them a strict education, so they had something to stand on. The kids saw her as really intimidating. I think they appreciated her more afterward.” Furthermore, said Feng, she found all the women she interviewed who were former refugees “really tough and resilient” and perhaps “more aware of what was going on, more understanding of what their parents had to do,” she said. “The boys were a little more sheltered. But I really loved the people I talked to, every one of them.”

My parents, now deceased, were among the refugees in Shanghai, and I was born there, so the story is not new to me. Yet I still found the documentary revelatory and moving, thanks in large part to Feng’s skill as a director.

The path my parents took was not unusual for this little-known chapter of Holocaust history. My mother was 18 when she arrived with her parents in 1939. They had owned a clothing store in Koenigs Wusterhausen, a small town near Berlin. The store and their home above it had been attacked the previous year during Kristallnacht, and they lived with relatives in Berlin while looking for a route out of Germany. Nearly every border was closed to them.

The only route they could find was to Shanghai, which had an international sector that did not require a visa to enter. They were allowed to take with them 10 Deutschmarks and one set of eating utensils each, along with clothes, photos and other items. They had to purchase first-class tickets on an Italian liner to Shanghai only packed into the back of a truck and taken to a refugee center set up by Baghdadi Jews whose families had arrived centuries earlier. Indeed, there is a long history of Jews flourishing in China, where anti-Semitism did not exist, as the documentary points out.

They soon ran out of money. My grandfather tried selling some of their excess clothing on the street, a common occurrence, but that wasn’t too successful. My grandmother, an excellent baker, tried to sell her cakes and cookies to restaurants—there was a flourishing café culture among the German and Austrian Jews—but that, too, wasn’t sufficient. It fell to my mother, Ilse Ludomer, to become the family breadwinner, because she could easily get jobs as a waitress. She was happy, released from snubs by her former German girlfriends, eviction from her public school, terror on Kristallnacht and denial of a swimming trophy she had rightfully won–hardships large and small for a teenager. She was enjoying the youthful life she had missed out on in Germany. My grandfather, who later died of tuberculosis, one of the many diseases rampant in Shanghai, was deeply unhappy.

My father, Erich Jacobsohn (before he dropped the h’s for America), came separately though also in 1939. He had a law degree but was prohibited by Nazi law from practicing. He had returned to his parents’ home in Stavenhagen, a tiny town in northern Germany. After Kristallnacht, he and his father were sent to a work camp. His father was released because of poor health and Erich because his mother purchased a ticket for him to leave Germany. He went to relatives in Switzerland first and then to Shanghai. It was, he often said, like sailing to the end of the earth. A refugee in the documentary likened the journey to “going into a black hole.”

However, like Ilse—whom he didn’t meet until 1945—he could find employment, most of the time. He knew English well and got jobs as a translator and teacher. He became a tutor for a boy whose father was the chief doctor in the city’s British sector. He socialized with other young people, mostly Jewish but sometimes Chinese. And, after the establishment of the ghetto restricted his movement and job opportunities, he often ate at the soup kitchen, as did the Ludomer family. But he didn’t meet my mother there. During an air raid drill near the end of the war, he managed to stand next to his pretty neighbor in a bucket brigade and introduced himself. The courtship began.

In 1946, my parents got married and a year later, I was born. When I was three months old, we left for the United States. My parents were refugees again and I, born stateless, became a refugee, too.

From Feng, I learned that displacement is a common thread in China, too. “My grandparents were also refugees, from a province next to Shanghai, because of the Japanese,” she said. “A lot of people in Shanghai were refugees from other parts of China, because of war with the Japanese since 1931. China has been a target of the Japanese for a long time.” The history of Jews struck a chord with many Shanghai residents, she said, because “they were able to survive and thrive, something Shanghainese look up to.” There are many cultural similarities, too, including “family values, attention to education, looking for ways to get ahead for a better life for their children.” Her mother worked as a nurse in Hongkou, where the ghetto had been, and she had a job starting from age 8 or 9 giving tours at the Shanghai Children’s Palace, a renowned center offering many after-school activities for Shanghai students that is located in a mansion once owned by a Kadoori family member. She learned English for the job, she said.

I discovered a few more personal ties with Feng, who is now 41. She studied journalism in Shanghai (I’m a journalist, too) and interned at CNN in Atlanta (the city where I grew up, and the media company where my son also had an internship while a college student). When she came to graduate school in Berkeley, she studied journalism and did a little newspaper writing (my background) before getting a master’s degree in broadcast journalism. She co-produced “Nanking,” which won an Emmy, and in 2015 she produced and wrote “Please Remember Me,” another award-winner, which she calls “the love story of my great-uncle and aunt, who had Alzheimer’s.” That illness had been looked down upon — the Chinese word for it, she said, means “old retard”—and her film “changed the narrative” about it in China. It also changed her own perspective about why she chose documentary filmmaking — it became about her ability to “make a difference.”

She feels the same way about her work on “Harbor from the Holocaust.” “I wanted to do justice to these people, so the story doesn’t go invisible,” she said. “I want to highlight this connection of the Chinese and Jews, this human connection, and these extraordinary people who stepped up. The feeling I got from the survivors is that they are appreciative of this place and felt that the Chinese people were kind.”

To top it off, Feng said she is now working on a documentary about “the empowerment of Chinese women,” focusing on an underground group of women who “have their own secret language. They live in secluded villages, they are the poorest of the poor, but these women were able to connect.” If there’s anyone who can translate that “secret language” into a universally resonant film, it’s Feng. I, for one, look forward to it.