After Loss, a Devotion to Those Afflicted by AIDS

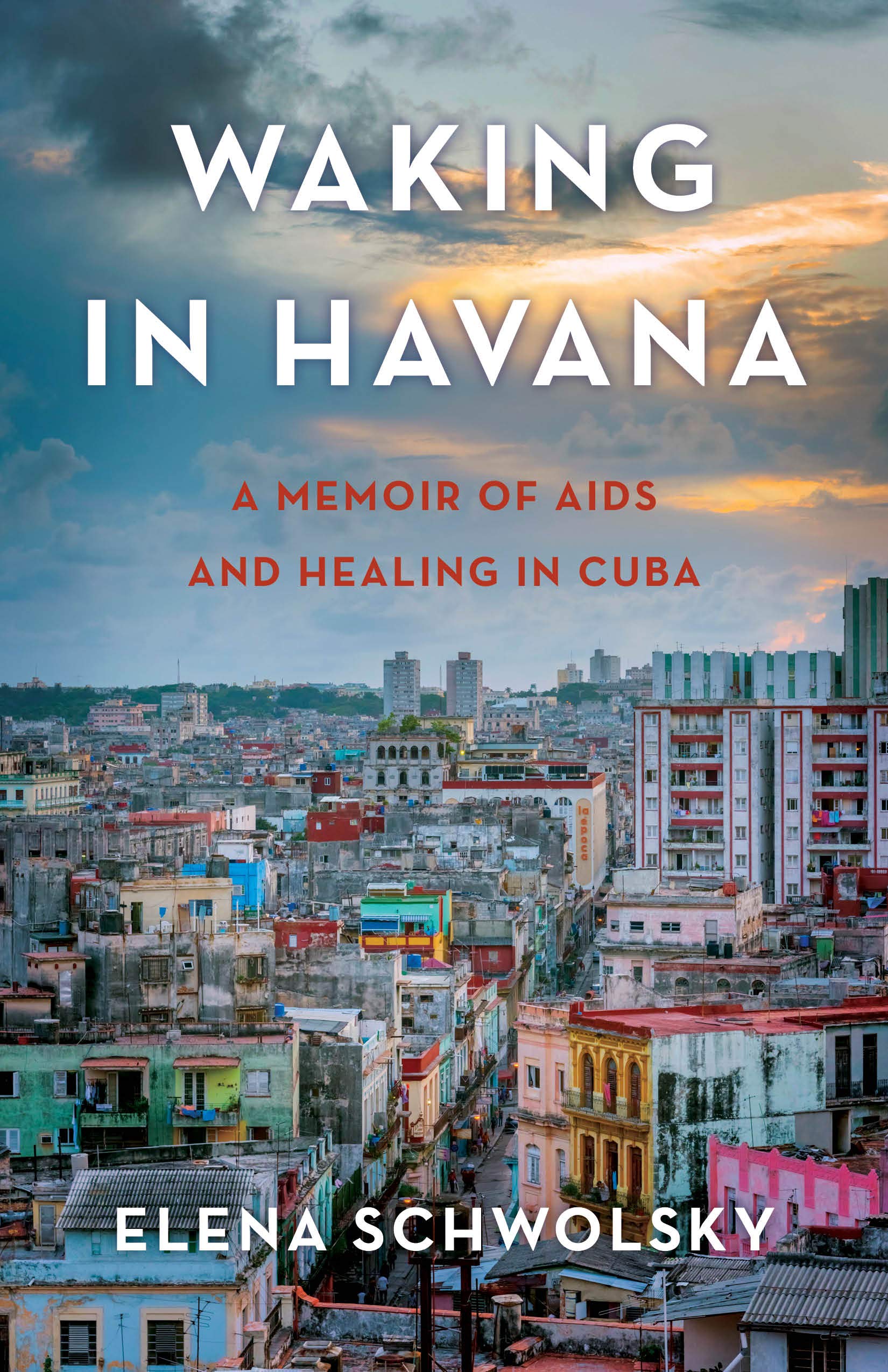

Not long after nurse and public health activist Elena Schwolsky’s husband, Clarence Fitch, died of AIDS in 1990, she left her job at a Newark, New Jersey, pediatric AIDS clinic, enrolled in graduate school, and went to Cuba to study the island’s AIDS treatment protocols and meet people living with the virus. The result of her six-month stay is the recently released Waking in Havana: A Memoir of AIDS and Healing in Cuba (She Writes Press).

Both deeply personal and deeply political, the book is a reflection on the challenges of living with HIV/AIDS and what it means to deliver humane medical care. The impact of the US embargo on Cuba and the collapse of the Soviet Union are part of the story, but Schwolsky’s focus never wavers from the individuals who are working to eradicate the disease. Likewise, people living with the virus are front-and-center in her moving, and often surprising, account.

Schwolsky sat down with Eleanor J. Bader in mid-December to discuss Waking in Havana, her ongoing AIDS work in Cuba, and the pervasive and persistent misconceptions about the island that continue to be promulgated.

Eleanor J. Bader: After working in a pediatric AIDS clinic and losing your husband to the virus, what made you want to do a deep dive into Cuba’s AIDS crisis?

Elena Schwolsky: I did ask myself if I really wanted to put myself in a Cuban sanitorium, where every resident had the virus and would likely get sicker and sicker. But Clarence had been on the frontlines and it somehow felt comforting to share in this work. It seemed like an important battle. I also think that I had survivor’s guilt. The universe had given me a pass and I felt committed to using my life in a way that had meaning. It gave me an identity, and the camaraderie in the AIDS service community had an urgency that bound us together. Plus, I was curious and wanted to see how the epidemic was handled in a different place.