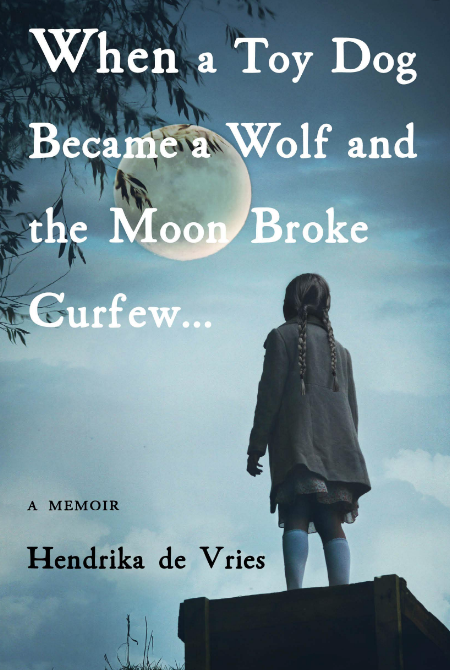

When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew…

In this new memoir, Hendrika de Vries’ writes of the dark days in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam as a child, years as a swimming champion, young wife and mother in Australia, and a move to America in the sixties. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis about how the brutality of her childhood fostered a strength and resilience she has been able to draw upon ever since.

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

HDV: At the time that my father was deported to Germany, I was an only child surrounded by friends and cousins who all had siblings, and I longed for my own brother or sister. I do not have a clear memory of how I felt when my mother decided to join the Resistance. In a way it seemed a natural progression, because we regularly spent time at the home of the family where members of the Resistance movement met. And when my mother told me we were going to hide a Jewish girl, I liked the thought that I would have an adopted older sibling. I was told that her name was Nel, but in order protect her secrecy I was not given her last name.

After she moved in with us, Nel and I formed a sisterly closeness and often slept in the same bed. In the manner of an older sister, she gave me a sweet diminutive nickname “Hennepiet,” and wrote about our “happy” time together in a poignant verse for the friendship album that girls my age carried around in those days. A copy of her verse with the nickname “Hennepiet” appears in my memoir.

Having been a daddy’s girl for the first five years of my life, I now learned about the comfort and unique pleasure of being in an all-female household. In my memory, my mom and my secret “stepsister” were always brewing pots of coffee and talking. If I close my eyes even today, I can still smell the rich aroma of coffee that permeated our home, and being in the company of their female bantering and laughter made me feel safe. I remember my mom bringing out a coffee-table-sized Old Testament copy of the Bible that had been in her family all her life. It showed full-page sepia illustrations of the Hebrews escaping slavery in Egypt. There was one of the parting of the Red Sea, of course, but the image I liked best was of Miriam, Moses’ sister, and other women dancing as they celebrated their freedom with tambourines. My mom, Nel and I would dance around our dining-room table clanging spoons and shouting “freedom” until my mom shushed us. I loved having an older sister. But I could not talk about her. She had to be our big secret. I could never figure out at six years old why the Nazis wanted to kill her, or might kill my mother and me because we were hiding her. I believe this confusion set me on my lifelong path to try to understand human behavior and my own eventual spiritual quest for the divine.