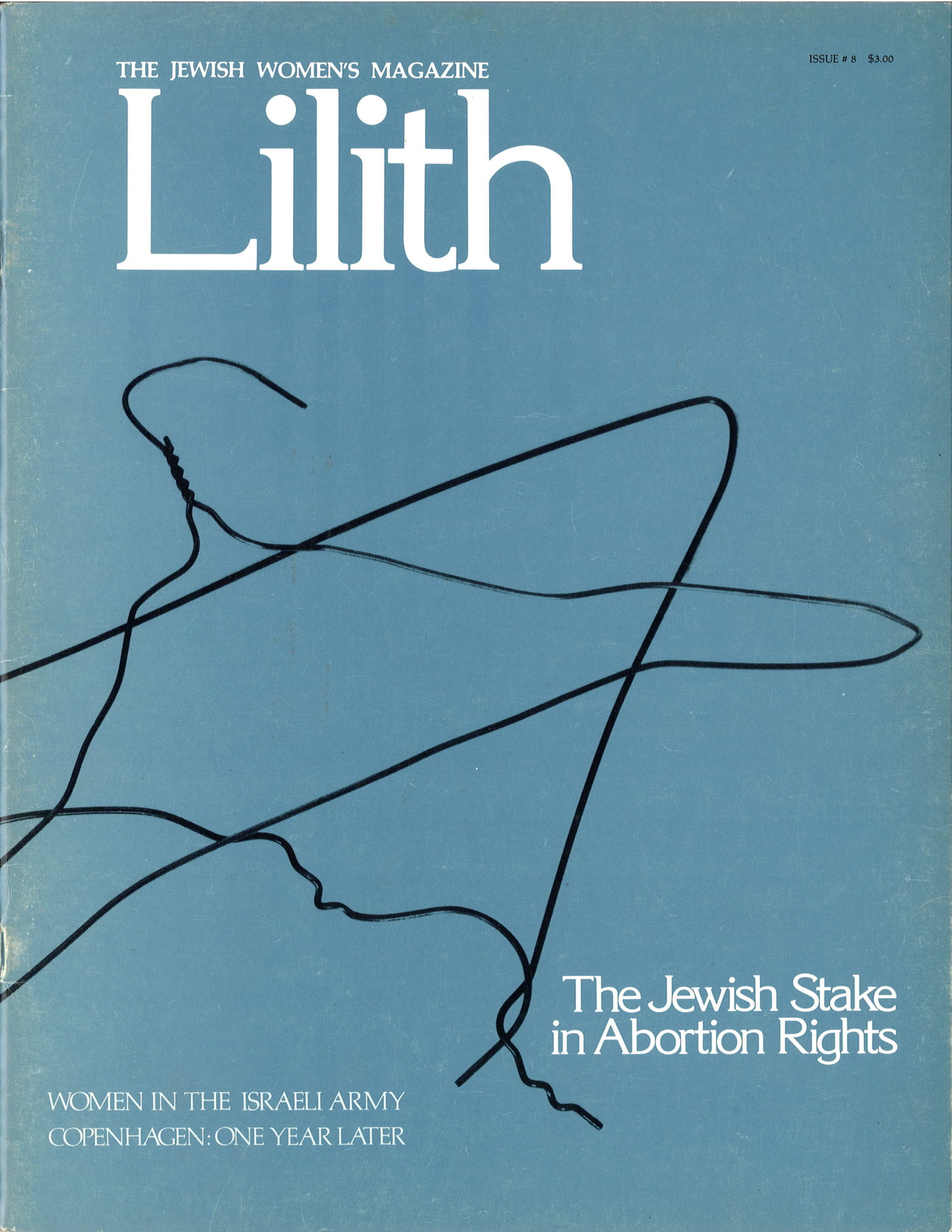

Escorting at an Abortion Clinic is Praying with My Feet

And it’s not easy. Anti-choice fanatics invoke gruesome imagery that compares abortion to genocide, to the Holocaust, to Mengele. Facing these images pierces me to my core. It can be next to impossible to drown out these messages, especially at 6 am on a Saturday morning. I could be asleep. I could be in shul, in a familiar, warm sanctuary surrounded by holy kindness.

But clinic escorting is holy, too. In each one of us is the Divine Spark, b’tzelem elohim. Every patient that I guide from their car into the clinic is created in the image of G!d. My work is to honor that, alongside my minyan of other escorts, through the mess of antis who cannot see or respect it.

These protestors are just one piece of the puzzle, though, emboldened by anti-choice extremism coming from the political field. The fight for the right to choose has reached a crucial moment: extreme bans on abortion are sweeping across the country and the domestic gag rule in full effect. Barriers to access abortion are getting bigger, doctors in some places are legally required to lie to their patients, and in many states it’s still legal to harass, lie to, and physically obstruct women who are trying to enter clinics.

So what does this have to do with Judaism? Surprisingly, a lot.

As Lilith readers know, abortion is permissible in Judaism. As Lilith readers know, many Jewish texts, including the Torah, life does not begin at conception and a fetus has no legal standing on its own. The fetus is considered to be a part of a pregnant person’s body, not a stand-alone being. Even Rashi weighed in here, stating that a fetus is “lav nefesh hu – it is not a person.” The Talmud contains the expression “ubar yerech imo – the fetus is as the thigh of its mother,” i.e., the fetus is deemed to be part and parcel of the pregnant woman’s body. And when the mother’s health is in danger, not only is it permissible to choose abortion, it’s mandated.

Secondly, and maybe most pertinently for me, Judaism calls us to action. It’s easy to refer to the age-old, “tzedek, tzedek tirdof,” “justice, justice you shall pursue.” The pursuit of justice is not simply about our own justice and justice for our loved ones, but pursuing justice for all. Additionally, Kavod Ha Bri’ot calls us to honor and respect the dignity of all people. And importantly, we must build the world with “olam chesed,” with lovingkindness.

What’s amazing is that to me, values almost line for line mirror the goals and values of WACDTF, the collective that organizes escorts:

-

To ensure that all people have access to all reproductive health care services that they desire.

-

To convey the message that all people have the right to control their own bodies and lives.

-

To encourage personal empowerment through action.

-

To keep the clinics open and functioning at the request of the providers.

-

To maintain a commitment to nonviolence at all times

Escorting also explicitly calls us to protect the dignity of those receiving care as they enter the clinic, a number of which may not even be seeking an abortion to begin withh. My job is not to judge, but to simply act as an enabler for healthcare.

On the other side, anti-choice extremists are legally allowed to stand outside of clinics where women access care and scream, hold obscene posters, preach and proselytize, and lie to the patients who enter the clinics. Some even resort to violence. They often physically obstruct the paths of those patients, especially in states with no buffer zone laws that mandate they stand a certain number of feet away from the clinic entrances. These experiences are traumatizing for women and, importantly, completely ineffective. Women who choose to have abortions are secure in their decisions. Part of a clinic escort’s job is to shield patients from this extremism and shuttle them safely into the clinic. Escorts are a literal buffer for the women choosing to exercise their rights.

By doing this, clinic escorts act with kindness and love. We care deeply about the patients we interact with, even if we don’t get the chance to learn their names. But that’s not what’s important. What’s important is that we can offer ourselves as guides amid a sea of horror and hate. We can, even for the briefest moments, offer a smile or reassuring word as we make our way to the clinic doors. This is olam chesed. This is how I practice my Judaism.

And then, after the last patient is safely back in her vehicle, and the last anti has put away their megaphone, I head to shul.