A Film About Faith… Starring Jewish Men, Men and More Men

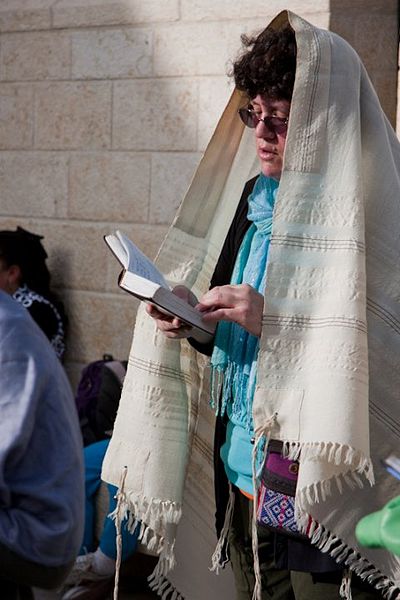

Which makes the film’s portrayal of Judaism all the more incongruous. I counted six or so vignettes depicting Jewish religious practice, as well as one featuring a secular Israeli family. Among the representations of Judaism were two circumcisions, a bar mitzvah at the Kotel, black hatted men praying in an airport, and frenzied Hasidim singing about Uman. This film about pluralistic religious practices offers little pluralism within Judaism, featuring men, men, and more men, all of whom appear to be Orthodox.

Watching “Sacred,” one could readily conclude that women do not participate in Jewish ritual in any meaningful way.

Lilith readers don’t need to be told that plenty of Jewish practices and ceremonies involve women, even in more traditional circles. Women are rabbis, even within Orthodoxy in recent years, heading some of the largest synagogues and creating some of the most successful “spiritual startups.” But you wouldn’t know this from watching “Sacred.”

One might also conclude from the film that there is only one kind of religious Judaism, that all religious Jews are Orthodox, or at least that the Orthodox far outnumber any other streams. Yet in reality, only 10% of adult American Jews consider themselves Orthodox, while more than half identify as Conservative or Reform (Pew, 2013). You wouldn’t know from watching “Sacred” that there are multiple liberal approaches to Jewish practice, and that these are significantly larger than Orthodoxy.

I emailed my concerns to Producer-Director Thomas Lennon, who replied, saying the filmmakers had sought a “rough overall balance between men and women.” Perhaps this is so for the other faiths depicted. He also noted that one film cannot present everything, leave everyone satisfied, or satisfy all competing priorities, which is a fair point.

Lennon noted that the film is about “moments of intense religious practice” as well as the “use of ritual, prayer and religious structure.” He encouraged me to consider the scene of the Israeli mother, shown with her family. She speaks about not knowing if there is a God, referring to the deity as “she,” which is intended to portray a female element in Judaism. Lennon sees the Israeli woman as introducing “a key theme in the film’s middle section: how religious men and women reconcile their faith with the fact that very bad things happen to good people.”

All of which would make sense if she were a practicing Jew. However, the Israeli woman is decidedly secular; her inclusion in the film does not illustrate religious practice, ritual, prayer or belief; she has no faith to reconcile. I was not successful in my attempts to explain this to Lennon. Perhaps he succumbed to the classic error of misunderstanding that being Jewish is not just about religion, that one can be fully culturally or ethnically Jewish without practicing Judaism.

As it doesn’t illustrate religion, the scene is at odds with the rest of the film. It feels like a gratuitous insertion to check the box of “Jewish and female”. But not only does the effort lack subtlety or sophistication, the scene further reinforces the point that the only religious Jews are Orthodox men. While we can’t definitively know whether this was intentional, the degree of imbalance in the representation of Judaism is blatant.

I expect that some, who practice a patriarchal, dorgmatic Judaism, might even be delighted to see “Sacred” usurped as a vehicle for delivering a message of exclusivity and intolerance. In the filmmakers they’ve found allies, perhaps unwitting ones.

Lennon wrote that “Before it was finalized, the film was shown to a range of religious consultants—including distinguished scholars of Judaism, male and female.” I find this surprising and troubling, and don’t know what to make of it, or of my being the only person to read the film this way, according to Lennon. Perhaps, consciously or not, the problematic images don’t register as they simply re-enforce the internal caricature of the Jew that begins with a bearded man in a black coat. None of the many reviewers seemed to have noticed either, or perhaps they did notice but found it acceptable.

We must notice, and we must declare it unacceptable. One of Judaism’s core strengths is its vibrancy, its ability to fuel multiple approaches, its ongoing evolution. There are many relevant and robust ways to be Jewish, many spaces where ritual is open to all genders.

We must reach for the real message of “Sacred” —that there are many varied forms of religious expressions, and that beauty is found in diversity. We must not allow Judaism to be defined by a subgroup intent on excluding others, and we must reject attempts to eliminate women and the non-Orthodox from the universe of religious Jews. We must not tolerate rigid, bounded depictions of Judaism policed by a narrow-minded minority. But mostly, we need to remain vigilant to such attempts, to see them, and to call them out when they happen.

Linda Rich is a consultant and coach who works with Jewish leaders and organizations, and can be reached at linda@lindarich.com. She curates Wandering Jews, a monthly listing of Jewish interest lectures in NYC: limmudny.org/learn-all-year/wandering-jews-nyc-events/

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.