The Thrill—and the Pain—of Exploring Córdoba’s Lost Jewish Treasures

After the official tour ended, two Jewish friends and I decided to explore by ourselves for a while longer. While wandering around the area, we happened upon Casa Sefarad, a museum a block away from the synagogue dedicated to Spanish Jewry and the Sephardi diaspora. By that point, my anger had turned into guilt. Removed by hundreds of years and thousand of miles from the medieval Jewish communities of Spain, I worried that my studies had exoticized them, treating the Middle Ages as a period of happy fantasy rather than one of serious grief and pain. How could I have been so excited to see a city in which so many Jews had been persecuted and tortured? I was apprehensive about entering the museum.

But slowly, as we wandered through the rooms, I felt the guilt begin to dissipate. Seeing the names of famous citizens of Córdoba on the wall, I realized that I’d learned about almost all of them in my classes, and in each room, I found myself adding commentary to the plaques in the museum, such as Bienvenida Abravanel, a matriarch of the powerful Abravanel family and one of the most influential women in Europe in the 16th century. Seeing room after room full of descriptions of the lifecycle of Jews of Córdoba, of the clothes they wore and the holidays they celebrated, reminded me that this community was made up of so much more than the persecution they faced.

The wall of the last room of the museum featured a poem I’d read many times before, written by a woman whose name has been lost to history, known today only as the wife of Dunash ben Labrat. Standing in front of the poem, I felt a litany of historical facts run through my head, from the discovery of the poem in the Cairo Geniza to the metrical scheme of the poem. But at the same time, standing in the place where this woman herself once lived, I felt, more strongly than ever, the emotional sentiment of the poem, experiencing it both as an important part of scholarly history and also simply as a striking poem.

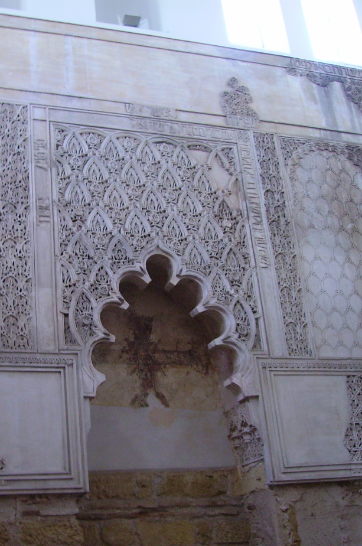

When I study their writings, I’m not ignoring the fact that life for Jews in Spain was full of challenges and dangers, but rather I feel I’m celebrating the fact that the Jewish community in Spain flourished despite those challenges. While anti-Semitism was of course a part of the lives of this woman and her contemporaries, it was just one facet. Her poetry, just as the poetry of her contemporaries does, paints a much fuller picture of life as a Jew in Medieval Spain than would records of the Inquisition or partially destroyed synagogues. Buoyed a little by this thought, as I left the museum and walked through the bustling streets of the city, I allowed myself once again to feel overcome with excitement at actually being in the place I’ve read about and imagined so many times.

One comment on “The Thrill—and the Pain—of Exploring Córdoba’s Lost Jewish Treasures”

Comments are closed.

I had similar emotions welling up in both Córdoba and Granada, especially after touring the Inquisition Museum. I spend a lot of time in Spain every May teaching in hospitals and that was the reason I was in both cities. My Christian colleagues, doctors and midwives took me to the places where they know Judaism was alive and flourishing, like the Beit Midrash in Tarragona, where Jews and Muslims studied each other’s texts and made discoveries in science, astonomy, physics and mathmatics. The awareness and appreciation is there in this generation’s acts to preserve, protect and restore. The Spanish government is offering citizenship to any descendant of Sephardic Jews in the Diaspora. I know a few who have accomplished this reconnection.