The Thrill—and the Pain—of Exploring Córdoba’s Lost Jewish Treasures

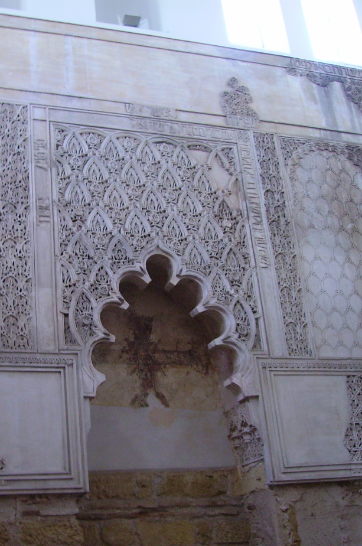

Arriving in Córdoba last month with my study-abroad cohort, I felt like I’d landed in a  medieval fairy tale. As my classmates and I walked across the bridge separating the main road from the town, we passed a castle, a swamp, and a bustling market full of people dressed in full Renaissance garb. After years of studying the literature and philosophy of the Jews of Córdoba, I couldn’t believe that I was finally seeing the city in real life. Walking down the streets, I snapped photo after photo of the white-painted buildings, getting increasingly excited as we moved through the judería towards the old synagogue, noticing landmarks that until then I’d only been able to imagine. It felt like the books I’d studied had come to life in front of me. Soon, we found ourselves in front of a small gate, blocked by a guard who waved our tour group into the synagogue area.

medieval fairy tale. As my classmates and I walked across the bridge separating the main road from the town, we passed a castle, a swamp, and a bustling market full of people dressed in full Renaissance garb. After years of studying the literature and philosophy of the Jews of Córdoba, I couldn’t believe that I was finally seeing the city in real life. Walking down the streets, I snapped photo after photo of the white-painted buildings, getting increasingly excited as we moved through the judería towards the old synagogue, noticing landmarks that until then I’d only been able to imagine. It felt like the books I’d studied had come to life in front of me. Soon, we found ourselves in front of a small gate, blocked by a guard who waved our tour group into the synagogue area.

But when I walked into the small chapel, seeing the partially destroyed verses from the Psalms on the walls and the tiny gold menorah in the entrance, my giddy excitement turned to anger. Anger that this small room was almost all that was left of a massive and influential Jewish community. Anger at our tour guide for glossing over the history of the Inquisition and Expulsion, and for not mentioning why one wall of the synagogue had a giant cross painted over it. And anger that, in the minds of the countless tourists who passed through Córdoba each day, the Jewish community would be reduced to a destroyed synagogue and a single statue of Maimonides. As we exited the building into the blazing sun, Córdoba seemed more like a place of disillusionment than the culmination of my studies I’d hoped for.

One comment on “The Thrill—and the Pain—of Exploring Córdoba’s Lost Jewish Treasures”

Comments are closed.

I had similar emotions welling up in both Córdoba and Granada, especially after touring the Inquisition Museum. I spend a lot of time in Spain every May teaching in hospitals and that was the reason I was in both cities. My Christian colleagues, doctors and midwives took me to the places where they know Judaism was alive and flourishing, like the Beit Midrash in Tarragona, where Jews and Muslims studied each other’s texts and made discoveries in science, astonomy, physics and mathmatics. The awareness and appreciation is there in this generation’s acts to preserve, protect and restore. The Spanish government is offering citizenship to any descendant of Sephardic Jews in the Diaspora. I know a few who have accomplished this reconnection.