#MeToo and the Women of the Bible

I’ve been studying and teaching these stories for twenty years, holding them up as examples of the transformative power of telling the truth about our lives. These characters are important and inspiring, and their stories remain as relevant today as ever. But as I watched some senators minimize Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s account of sexual assault last months, another critical element of these stories has come into focus for me.

The heroines of these stories are the women who dare to challenge discrimination and call out abuse. But equally important are the people in power who listen to the women with humility, wisdom, and a commitment to justice.

Perhaps some of the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee should study their Bible a little more deeply.

Take, for example, the story of the five daughters of Tzelofchad, a character who appears in Bamidbar (Numbers). We know very little about the character himself. What we do know is that after he dies, leaving no sons, his five daughters appear in court to argue for a woman’s right to inherit land.

Their appeal is limited to families without sons. Still, it’s a radical demand by five women in the ancient world. Moreover, when these women take their complaint to the highest court in the land, the judge – Moses— has the humility and wisdom to consider the merits of their case. He rules in their favor, and the law is changed.

Another example from a less obscure story: Hannah and the High Priest. Hannah, a young wife yearning for children, prays in the ancient Temple with such intense abandon that the High Priest kicks her out, assuming she’s drunk. Rather than accepting her fate, Hannah returns and argues her case before the High Priest. She corrects the highest spiritual authority of her time, explaining that she was simply transported by her prayer. Here, too, rather than shame or denounce Hannah, the High Priest apologizes. He acknowledges that Hannah is in the right, and her prayer will be granted.

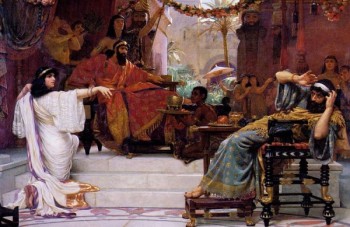

A third and the most well-known example, the story of Queen Vashti, reads today as a cautionary tale for leaders who fail to listen to women. Vashti’s husband, King Ahasuerus, is so desperate for the admiration of his subjects that he throws a week-long open bar party for the men of his kingdom. At the end of the week, he commands his queen to appear in her royal crown, to display her beauty before the men. Vashti refuses. (A famous commentary suggests that the king commanded her to appear wearing only the royal crown.) At this, the King’s advisors insist that he divorce and banish her. “Otherwise,” they say, “All the women will think they no longer have to obey their husbands!”

The King, susceptible to unwise counsel, agrees. Soon after he banishes Vashti, he is convinced by an evil advisor to kill all the Jews in his kingdom. The genocide is averted only when the King’s new wife, Queen Esther, who is Jewish, reveals her heritage to him. It’s a risky move, but she is urged on by her uncle, who tells her, “Perhaps for such a time as this, you have risen to power.” With power comes the responsibility to act with discernment, humility, and courage.

These stories are ancient. Yet through time, they make it clear that the imperative to listen carefully to those with less power is a fundamental human challenge, one every generation’s leaders will be called to meet.

Vashti, Esther, Hannah, the daughters of Tzelofchad. In our time, Christine Blasey Ford takes her place among these heroines who made the wrenching decision to speak out, risking everything for the sake of the truth and justice.

I was hopeful that the men and women of the Senate would meet the challenge and follow the example of Moses and the High Priest, those powerful ones courageous enough to truly listen. Instead, they acted like King Ahasuerus, unable to see the humanity of those standing before them.

Alicia Jo Rabins is the author of Fruit Geode and the creator of Girls in Trouble, a musical project about the women of Torah.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.