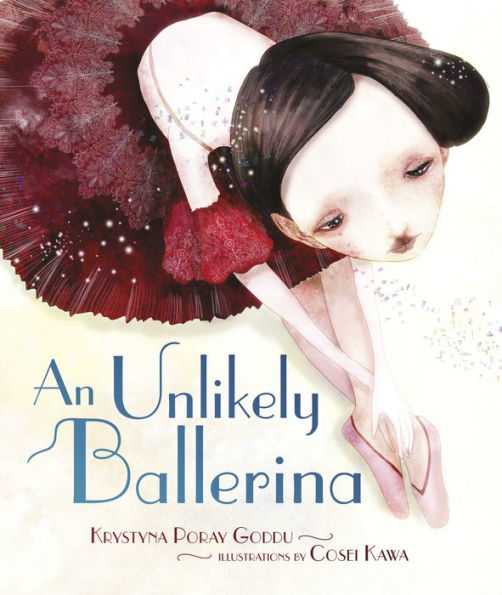

The Book That Teaches Children About a Jewish Prima Ballerina

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Lily Marks?

KPG: A longtime dance lover, I went down to Washington, D.C., in September 2013 to see the National Gallery’s exhibit entitled “Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music.” It was absolutely breathtaking—original costumes and set designs by Matisse, Picasso, Chanel (among other luminaries) on display, along with photographs, posters, drawings and many performance clips. At that exhibit I was intrigued to learn about Diaghilev’s youngest soloist, Alicia Markova, actually an English girl named Lily Marks who had been born with disabilities in her legs. One of my first thoughts was that Lily’s story might make an inspiring subject for a children’s book. And right around that time, a small item in Vogue magazine entitled “Markova as Muse” caught my interest, and I clipped it. It was about a new book coming out that autumn: The Making of Markova by Tina Sutton. So, of course after I saw the exhibit, I had to have the book. The more I read about Lily’s early life, the more I thought I wanted to write about her for children. I had never had any success in writing picture books, so it was a very long process from learning about her to having a completed manuscript (which underwent many many revisions before, and after, finding a publisher). I’m very grateful to Joni Sussman at Kar-Ben for sharing my excitement about Lily’s story and signing up the book.

YZM: What was the reason for Liliy’s name change to Alicia Markova?

KPG: Serge Diaghilev believed that at the time (1920s), nobody would come to see a British ballerina. In his view, audiences expected all ballerinas to be Russian. And his company was, after all, the Ballets Russes. Markova wasn’t the only one with a changed name. Lydia Sokolova had been born Hilda Tansley Munnings in Essex, England, and Ninette de Valois was originally the Irish Edris Stannus. As it happens, Lily’s middle name was Alicia, after her great-grandmother, and she began using it instead of Lily when she began dancing professionally at the age of 10. She thought Alicia Marks was a better name for a dancer than Lily Marks. She was very disappointed when she officially joined the Ballets Russes at the age of 14 and Diaghilev barely changed her name at all. She wrote in her journals that she longed to be “Olga.”

YZM: Had you known at the outset that Alicia Markova was Jewish?

KPG: I honestly don’t remember if that was mentioned in the Ballets Russes exhibition, and it definitely wasn’t in the Vogue item. But as soon as I had Sutton’s book The Making of Markova in my hands, I understood that her being Jewish was very much part of her legendary status. She is regularly identified as “the first Jewish and first British prima ballerina assoluta,” even though it’s widely believed that Anna Pavlova, to whom she was always compared, was Jewish.

YZM: How did her Jewish background affect her life? Did it work against her at any point?

KPG: I looked into her Jewish background as thoroughly as I could but couldn’t find any evidence of her family observing the Sabbath or other religious practices during her childhood in any of the writings by or about Markova–though her Irish mother did convert from Catholicism to Judaism when she married Arthur Marks. Corresponding recently with Sutton, though, I learned that the Marks were indeed a religious family. She told me that in Markova’s archives she had saved their yearly tickets to the High Holy Days services at their local Temple, as well as her father’s tallit, which she later wore on Shabbat with her mother and sisters after he died, taking over the traditional “male” role as the eldest child. They weren’t Orthodox, like her grandparents, but they said prayers and lit the candles Friday evenings and attended Temple – though Sutton doesn’t know how often. She also writes about Markova feeling discriminated against after Diaghilev’s death and the folding of the Ballets Russes. Sutton attributes anti-Semitism to Markova’s exclusion from the opening performance of a new dance organization called the Camargo Society and, apparently, the well-known dancer Lydia Lopokova (Mrs. John Maynard Keynes) made no secret of her dislike for Markova due primarily to her Jewish background (though also because Markova was a competitor in the ballet world).

YZM: What’s a question you wished I’d asked about this book?

KPG: I guess I’d like to talk about her dancing! Her story is worth telling, after all, because she was such an extraordinary dancer: incredibly strong in spite of her small stature, breathtakingly light on her feet—“ethereal,” people wrote—precise, fluid and versatile. She’s always associated with Giselle—in fact her memoir is entitled Giselle and I—and I was amazed to read in it that she was still dancing the role at the age of 50! And, of course, I’m very interested in how important she was in the American dance world: helping found what became the American Ballet Theatre and helping keep Jacob’s Pillow afloat in the summer of 1941, when she and her longtime dance partner Anton Dolin ran it as a summer dance school for the first time. And then she danced in Israel, under difficult conditions, to help celebrate the Tenth Anniversary Year of the State of Israel. She was a seminal figure in the international world of dance. That’s why the story of little Lily Marks overcoming her flat feet, knock knees and frail legs is so important—she was so talented and so generous with her talent.