Who Is A Radical Feminist?

Before long, Antler took the podium. She spoke to some of the highlights of her forthcoming book, and discussed the hidden Jewish identities of many radical feminists who defined the future of American feminism. The most surprising of this discussion? That eight of the nine original members of the “Our Bodies, Ourselves” collective were Jewish. Jewish identity was not overt in “Our Bodies, Ourselves” activism, nor was it a discussion piece in most of the women’s liberation movement. Nevertheless, standing against oppression and engaging in the work of liberation itself, Antler argues, likely shaped the values of Jewish women as they performed the cultural work of activism.

The intergenerational panel of four Jewish women after Antler’s address discussed at length Antler’s book, and the intersections of their own identities as Jews and feminists. They showed more pictures of the women in the audience at protests and marches in the 1960s and 1970s, and celebrated the “movers and shakers” of women’s liberation. A young Heather Booth walked at a demonstration in Chicago advocating for affordable childcare in May 1971, her toddler son clutching to her as she smiled for the cameras. These photographs are more than windows to the past: the Jewish women represented in the book merged the personal and political to campaign for reproductive rights, LGBT rights, and Jewish rights on a communal and national level.

A telling moment of the night for me was the discussion of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In light of the new documentary about her life, “RBG,” an audience member asked what her place was in the radical feminist movement. “She didn’t consider herself a radical feminist,” one of the panelists said, “She didn’t like protests. Her work was in the law. She preferred to enact change quietly.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not hold signs on the front lines of protests. Her approach to dismantling systems of oppression was not to reject the system, but instead to work within it. But she was a key part of a massive generational shift.

The radicalism celebrated at this event was explicit, front-lines work of consciousness-raising and protesting. And that work is admirable—some of these women have persisted through forty, fifty years of activism. But it also made me wonder about the Jewish women who made change in quieter ways, in tandem with the protests and gatherings.

I thought of Ginsburg, who used the Constitution to gain equal rights and protection for women. That she does not consider her career as a lawyer and judge radical makes sense, but it depends on how you define radicalism. And I also thought of the women who could never make it to a protest. The women who were busy raising children, who would lose their jobs if they tried to defend the rights which the women’s liberation organizers were fighting for. These women could not call for the reordering of society, because they had too much to lose if they rejected it. But they may have made their own quiet changes in their workplaces, or through how they raised their kids, that pushed society along just as surely as the marches did.

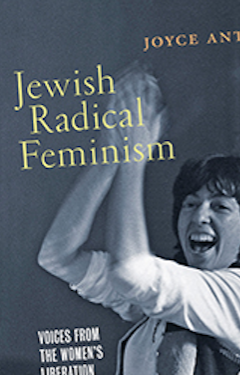

The women profiled in Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices From the Women’s Liberation Movement were radical in that they actively pushed against social structures, whether in the family, the workplace, or the synagogue. The celebration of the forty women in Antler’s book is important, and she has done crucial work for history by recording their stories. As we use this history to look forward, we should do so with the knowledge that there is more than one way to express desire for change. It can come from dismantling norms, or from working within them—and both approaches can be radical in their own way.