Ruth: the Torah of Transgressive Transformation

These three women all draw on the biblical legal rule (“levirate law”) that if a husband dies without having fathered any children, his widow is entitled to marry and have children with his brother. If the brother refuses, he is subject to public contempt.

In the first of the three tales, after the explosive destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot’s daughters (who have escaped along with Lot) are convinced that all the men in the world are dead, and in order to have children they get their father drunk and have sex with him. The child that is born to one of them is named Moab (which could be understood to mean “from daddy”). He becomes the head of a tribe and the ancestor of Ruth the Moabite.

We will come back to Ruth. Meanwhile, long afterward, one of Joseph’s brothers, Judah, marries one of his sons to a foreign woman, Tamar. His son dies, with no children. In accordance with the law, Judah marries her to his second son. But he too dies, leaving no children. Under the law, she is entitled to marry a third brother. But Judah fears she is jinxing his offspring, and prevents a third marriage.

But Tamar knows that she is entitled to have children by some member of this family. She pretends to be a prostitute, seduces Judah himself to sleep with her, and has two children. Judah is on the verge of burning her at the stake for adultery, when she explains what she has done and he affirms that she is more righteous than he is. So she, like Lot’s daughter, has invoked a peculiar – even outrageous — version of the levirate law.

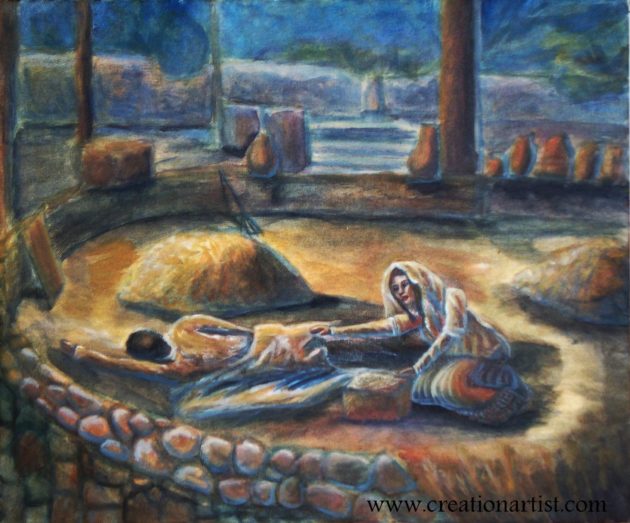

One of Tamar’s children becomes the ancestor of a prosperous Israelite landholder, Boaz. Yes, the same Boaz who connects with Ruth the Moabite. Ruth’s Israelite husband has died, leaving her childless. When she accompanies her mother-in-law Naomi to Naomi’s home in the Land of Israel, she gleans in the fields owned by Boaz. He goes out of his way to warn the young men working in his fields not to harass her. She ventures onto the threshing floor where Boaz is sleeping, and breaks the rules of conventional behavior by “uncovering his feet.” (“Feet” in the Hebrew Bible is often used as a euphemism for the genitals.)

Boaz, powerfully attracted to her, discovers that he is a distant cousin of her dead husband. He appeals to a far-fetched version of the levirate law about a childless widow, and marries her. She has one child.

So these three women, all outsiders to the Jewish people, have stretched the law beyond its normal understanding, in order to bring their children into the world. Then the story of Ruth goes out of its way to announce that Ruth’s own children will become the ancestors of King David – – and they do. Since Jewish tradition insists that the descendants of David will give rise to the Messiah (and Christian tradition specifically mentions Ruth as an ancestor of Jesus), in both traditions these three transgressive women are said to make possible the peaceful transformation of the world.

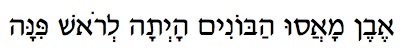

In this complex interwoven tale, there is a subterranean assertion of what the Psalmist says in open song: “The stone that the builders rejected will become the cornerstone of the Holy Temple.” The women who are “supposed” to be subordinate have subversively turned history around.

Click here to hear Rabbi Shefa Gold chant:

http://www.rabbishefagold.com/cornerstone/

Evven ma’asu habonim ha’y’tah l’rosh pinah

The Stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone. (Psalm 118:22)

Notice that each separate story breaks the rules, and their culmination becomes a vision of Messianic time — which also “breaks the rules,” for ultimate good. As if to say, live a raindrop here, a drizzle there –- and suddenly the rain becomes a river.

How did the biblical text evolve into this effort to go beyond itself? The thread that tied the separate stories together was the Book of Ruth. And many modern scholars understand Ruth as a polemic in a major political/ spiritual debate. A debate about the boundaries of the Jewish people, and a debate about the role of women in those boundaries.

When the Jews who had been taken into Babylonian Captivity were permitted by the new Persian Empire to return to the Land of Israel and were handed power over those Jews who had never left, the returnees faced a question: Many of the men they met “back home” had married women who were not Jewish. Could this stand? Could the culture stand it?

The leaders decreed that all “foreign” women must be divorced. The Book of Ruth seems to have been an attack on this draconic policy. Its heroine was an outsider, and she became the forebear of King David. Should “foreign” women really be forbidden?

An actual struggle in the body politic led to an amendment in the sacred text. And then the sacred text remained a thorn, at least a puzzle, in the body politic. We see an interplay between sacred text that grows itself beyond itself, and communal change that reshapes old forms into new paradigms.

Perhaps that is the deepest reason for us to read the Book of Ruth when we welcome Revelation of the Torah: a teaching that new Torah may come from earthiness, more than from heaven. “For not afar in Heaven is the Torah-connection but very near you, in your mouth and in your heart, to love the Breath of Life!” (Deut 30: 11-16)

A lesson for today. For Shavuot, and every day.