https://www.flickr.com/shawncalhoun

The Stories We Tell

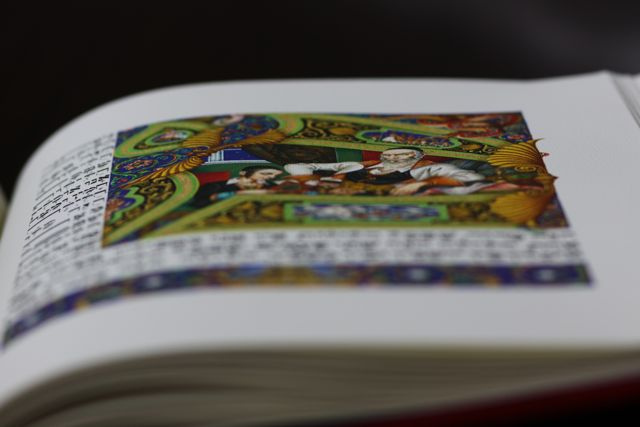

The Passover Seder is one of the most widely observed of Jewish rituals, and it’s no wonder. Copious amounts of wine, food, and a good story are bound to draw a crowd. With the focus all too often on the brisket and Merlot (or in many Jewish homes, the Malvasia), it’s easy to forget that the food and wine flow – pun intended – from the story, and not the other way around.

Passover is at heart a storytelling holiday. For it is written, “And you shall tell your child on that day saying. ‘Because of this God did for me by bringing me out of Egypt.’” (Shmot 13:8). Rooted in this verse, the Passover Haggadah is essentially a children’s book, the seder an extended bedtime story. The Exodus is in many ways the story of the Jewish people––the one where we become who we will be (for a while, anyway), a self-governing nation with our own homeland. The seder, then, is not just about telling a story but teaching our children––and reminding our adult selves––about our collective values and identity: This is who we are, this is where we come from, this is what we believe. The matzah, bitter herb, and the rest of the items on the seder plate are not just symbolic foods but visual and gustatory aides to help bring the story to life, to make the pain and suffering of slavery, and the elation at being free, into something tactile, experiential and real. We are not just obligated to tell the story, but to feel as if we ourselves are going out of slavery in Egypt, wandering through the desert, and then ultimately finding ourselves a free and sovereign people in the land of Israel. Hallelujah!

Good stories convince us of their truth, even if they are fictional.

But this is true for any good tale: the best stories draw us in, transporting us to their native time and place, making us feel what the characters feel. Good stories convince us of their truth, even if they are fictional. We see ourselves and our lives reflected in them, or we see a better version to which we can aspire. And, like the best of bedtime stories, the hagadah is not meant to be raced through or read verbatim like a lecture. Rather, it should be more like a discussion guide, elicit questions and conversation among guests, and especially between parents and children. The Four Questions, coming right off the bat, offer a jumpstart to the discussion. The mini-tale of the Four Children is often read as a description of four different educational models. The four cups of wine, well, they are supposed to be a symbol of our newfound freedom and wealth, or of the four ways God saved us from Egypt; but perhaps they are also meant to loosen us up so we can ask the really tough questions and offer the truest answers, the ones our sober selves might be too afraid or too reserved to say out loud. (Possibly, the wine is there to make it easier to bear so much time with family. Really, the rabbis thought of everything.)

The looseness of the Haggadah means it can bend to the will and values of the seder leader and participants. This is why there are so many different variations on the Haggadah and so many innovations on the seder ritual. Miriam’s cup, an orange on the seder plate, women’s seders, social justice seders, vegan seders; I even recall a chocolate seder in college (for those who value chocolate above all else?). Even in traditional seders, where each word of the standard Hebrew text is read, every family has its own personal rituals. One seder we go to involves costumes, and throwing candy to symbolize the 10 plagues. Talk about getting children excited! Some Sephardic families whip each other with scallions or leeks. The way we tell stories can tell as much about our values as the content of those stories. (Insert your own joke about the values illustrated by scallion-whipping.)

All of this got me to thinking about the other stories we tell children in order to teach specific lessons or to present certain versions of ourselves and the world, however aspirational those may be. So I asked a few thoughtful Jewish women I admire to tell me their favorites, then realized that the women I chose are all storytellers! Some are writers who have forged new paths with their words. Others are making changes in our communal Jewish story, having an impact on the way we live our lives and the way we see ourselves. Some do both. Here, they reveal the stories they love.

From Rabbi Sharon Brous, Founder/Senior Rabbi of IKAR, a congregation in Los Angeles:

“Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge [by Mem Fox] is one of the most beautiful and poignant children’s stories I have read, and a family favorite. It’s the story of a young boy who lives next door to an old age home. The residents are his closest friends. When he overhears his parents saying that one of the old folks is losing her memory, he goes on a quest to figure out what memory is and help her find it again. It is deeply touching and a great opening to a conversation about love, memory and aging.

“We love to read our kids books about the Civil Rights Movement like Martin’s Big Words and Rosa (the story of Rosa Parks). My personal favorite is Moses [by Carole Boston Weatherford and Kadir Nelson]. It tells the story of Harriet Tubman’s journey from slavery to freedom, giving voice to her inner journey as dialogue with God. Her faith and courage are deeply inspiring and it’s absolutely breathtaking to get a window into her understanding and engagement with God.

“We also love Journey [by Aaron Becker], a gorgeous wordless book that lets the kids narrate their own stories. It’s about a child who is feeling alone and lonely, who sets out on the journey of a lifetime to find a friend. It’s stunning.”

From Blu Greenberg, founder of JOFA, author of On Women and Judaism and other books:

“In the category of secular books, my all time favorite is George and Martha, The Complete Stories of Two Best Friends [by James Marshall], an under-appreciated classic. I’ve read it to my grandchildren hundreds of times and never tire of it, partly because the short vignettes about two hippopotami impart valuable lessons about life and relationships — not just kindness and sharing but also privacy, forgiveness, empathy, self-esteem; and without being preachy, about the two-edged sword of pranks, stubbornness, vanity and more. I never tire also because, amazingly, no matter how many prior readings, I discover a new message each time.

“When I was growing up, Jewish books for children were few and far between and were mostly about gendered roles for Jewish children – Avrumi getting tzitzit and Rivka preparing for Shabbat. Today, one need look no further than the great PJ Library series for both Jewish classics and creative new authors. My current PJ favorites are Someone for Mr. Sussman [by Patricia Polacco] about a shadchan who marries her client, and Bone Button Borscht [by Aubrey Davis and Dusan Petricic], about generosity in a poor shtetl. Delicious stories.”

Daphne Merkin, novelist and critic, author most recently of This Close to Happy: A Reckoning with Depression:

“I remember loving All of a Kind Family [by Sydney Taylor]. It was the story of a large, German-Jewish family, with immigrant parents, like mine was. I identified with Sarah and her four sisters. All of Kind Family had the life force of Little Women, but I could relate to it more. And without being sugary, which Little Women could be, it was very warm-hearted about the immigrant experience. The family was struggling but not impoverished. It felt like both an extension of, and alternative to, my own life. I think I wanted to be part of THAT family.”

Tova Mirvis, author most recently of Visible City and the forthcoming memoir The Book of Separation:

“The Carp in the Bathtub [by Barb Cohen and Joan Halpern] has always been one of my favorite children’s books––and I think about it to this day, sometimes crediting it with inspiring me to become a vegetarian. What I love about it is the way it conveys compassion for the plight of the fish, but allows that compassion to extend as well to the mother who is tasked with cooking it. It’s a book that exudes empathy without sugarcoating the dilemma, and taught me that you could see a situation from many points of view, and feel compassion all around.”

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, activist and author, most recently of the novel Single Jewish Male Seeking Soul Mate (and a contributor to the classic Free to Be You and Me):

“The Adventures of K’ton Ton [by Sadie Rose Weilerstein]. Until adolescence, I was always small for my age, which may account for my identification with, and delight in, the tiny little boy at the center of these wonderful stories. I loved K’ton Ton’s spirit, whimsy, and daring. I’m sure I especially connected with his exploits because so many involved traditional Jewish objects, food, and traditions with which––having grown up in an observant Jewish household in Jamaica, NY––I was intimately familiar.”

Chava Shervington, President of the Jewish Multiracial Network:

“The People Who Could Fly [by Virginia Hamilton] is an amazing folk tale about a group of slaves who possess these ancient, magic words that enable them to fly away to freedom. It is centered on the black experience but in a way that honors heritage and tradition. The people weren’t really free (which I didn’t realize when I was a kid), but it’s about the idea that even though they were enslaved, you can never really enslave the whole person. There’s always a part of themselves, their spirit, that remained free. There’s a tendency in American culture, in stories about slaves, to distance the slaves from the heritage and culture they had back in Africa before they became slaves. Reading this book was one of my first experiences with the idea that black history didn’t begin in America.”

Dr. Sharon Weiss-Greenberg, Executive Director of JOFA

“Free To Be You and Me [by Marlo Thomas and Friends]. This may seem cliche, but as much as I try to raise my preschool age boys as feminist, stories offer a modality that is highly effective in imparting values. They learn that a patriarchy, with princesses without locus of control, are old tales that are being illustrated as out of touch and dated. I want them to question the status quo, especially as it relates to gender, and they learn how to do that from William and his doll, from the girl who cried ‘ladies first’, to the two newborns discussing gender stereotypes without even knowing their own sex. The lessons are relayed in a humorous, engaging manner, and I just love their reactions.”