Making Murals in the Public Interest

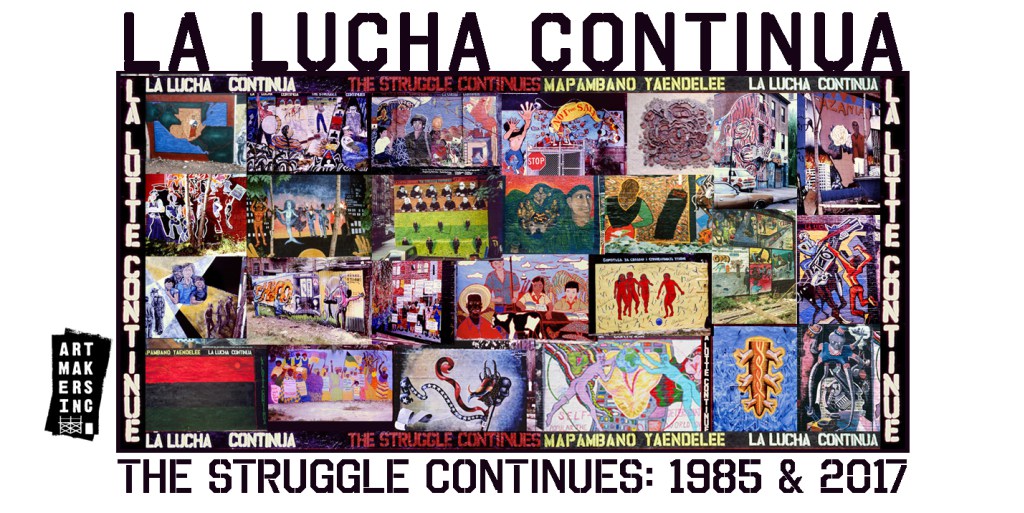

The La Plaza Cultural’s murals—covering a total of 6645 square feet—were called “La Lucha Continua The Struggle Continues,” and were intended as a way to celebrate activism, pay tribute to martyrs lost to the struggle for social justice, and depict the pride and strength of the diverse Loisaida/East Village community. Like all Artmakers’ work, the panels were meant to inspire, uplift, and beautify.

“Murals are an ephemeral art form,” Jane Weissman, Artmakers’ Administrative Director told Eleanor J. Bader in a recent interview for Lilith. La Lucha Continua is no exception; only two of the 24 murals remain and both are badly cracked and faded.

Nonetheless, a photo exhibition, called “La Lucha Continua The Struggle Continues: 1985-2017,” is now on view through July 31 at The Loisaida Center—710 East 9th Street in Manhattan—which offers multigenerational programming that appeals to the social and cultural sensibilities of the Lower East Side.

Eleanor J. Bader: How did you become an Artmaker?

Jane Weissman: I became the director of a New York City program to encourage community gardening, called Green Thumb, in 1984. When I arrived one of our consultants was developing a proposal for a project that we thought might appeal to funders if we lost our federal grants. The project, called Artists in the Gardens, started bringing murals and sculptures into community gardens in 1985.

In 1986 I met Artmakers’ founder, Eva Cockcroft, when she won a Green Thumb commission to paint a mural at 142nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Harlem.

Several years later, in 1998, after I’d left Green Thumb, I participated in my first Artmaker project, a mural in the Bronx. That first mural was called “Venceremos—We Will Overcome,” and from that point on I’ve been an active Artmaker.

EJB: How do the themes touched upon in La Lucha connect to, or diverge from, today’s political climate?

JW: In 2015, we realized that it had been 30 years since the La Lucha murals were painted, and as we began looking at the themes, we realized that the issues have not gone away and may even be more critical now. Four of the themes—gentrification, feminism, police brutality, and immigration—are especially relevant. People of color continue to be killed by the police. This has led to the development of the Black Lives Matter movement, but police officers are still rarely punished for killing unarmed people. Roe v. Wade is at risk of being overturned and poor women continue to face unequal access to high-quality healthcare; Planned Parenthood funding is threatened; and women earn, on average, just 78 cents to the male dollar. On top of this, many immigrants live in fear of deportation and this administration has made countless anti-immigrant and anti-refugee statements. Gentrification, of course, is ongoing, and causes a lot of displacement in low-income areas.

The artists of conviction—that’s how the La Lucha muralists referred to themselves—who painted the La Plaza murals, were also opposed to U.S. intervention in Central America, which was then a big concern. Today we see the rise in militarism and the ongoing wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen. As for opposition to apartheid in South Africa, well, if you look at the state of race relations throughout the world, it’s often apartheid in all but name. The same issues plague us, even if the locations or names change.

EJB: Will any of the artists who painted the La Lucha murals be present at the upcoming exhibition opening?

JW: Yes. I was able to track down 30 of the 34 artists—three have already died—and discovered that 18 of them were women. Interestingly, only a few of them are still working as muralists. Some have gone into the healing arts, massage or reiki. One is making jewelry, another is a photographer, and two became graphic designers. Only three women are still painting murals, but all of the people who had been involved in the project were excited to talk about it and reminisce.

EJB: How did the East Villagers in the 1980s respond to the La Lucha artists coming into their community and painting the murals?

JW: For the most part, everyone was welcoming. Kids would come around, and several of the artists set aside a place where they could paint or use Crayolas without having to get up on ladders. One artist told me that making the mural was like being in a performance piece. There was an outdoor car repair shop run by a guy name Junior in an adjacent lot, and people would come by, hang out, and talk to him throughout the day. They’d bring food and beer and would watch the painters as they worked. After a while some of them started to bring food to the artists. Quite a few of the artists contacted mentioned the kindness of the community. Of course, there was some initial skepticism from neighborhood residents. Who were these people, and why were they painting the walls of these buildings? But it was minimal.

There was one small conflict though. One of the artists, Camille, who had grown up in France and remembered running around naked as a child, was doing a painting that included some kids. She painted them without clothes, their genitals showing. One day Eva came over to her and said that a resident had complained. She was upset that the genitals were visible. In deference to the community, Camille altered the mural, amused that “her children” had to be neutered.

EJB: Were there other challenges?

JW: The mural was painted outdoors in the summer, so it was hot and humid. And even though all of the painting was done by volunteers, Artmakers still had to raise at least $3500 for supplies. Another big issue was that many of the walls were covered in tar. Building owners often slap a coat of tar on a building when leaks develop since it’s the cheapest way to fix the problem, but tar expands and contracts with the weather. This made the painting extremely challenging.

EJB: What do you hope viewers of La Lucha Continua The Struggle Continues: 1985 and 2017 will take from the exhibition?

JW: The show will be a celebration of the La Lucha murals but it will not be a blind celebration. It is meant as a reminder that not a whole lot has changed since 1985 and there’s a great deal of work that remains to be done to create a fairer, more just world. I hope it will inspire people to find some way to be active, maybe through the arts, maybe in another way. In 1985 there were so many political organizations out there. Artists were banding together to champion opposition movements. In the last few months, since Trump was elected, artists have again begun banding together to create visual opposition to the administration’s policies. Artmakers wants to encourage that. Plus, the exhibit will give people a chance to see some really, really great murals!