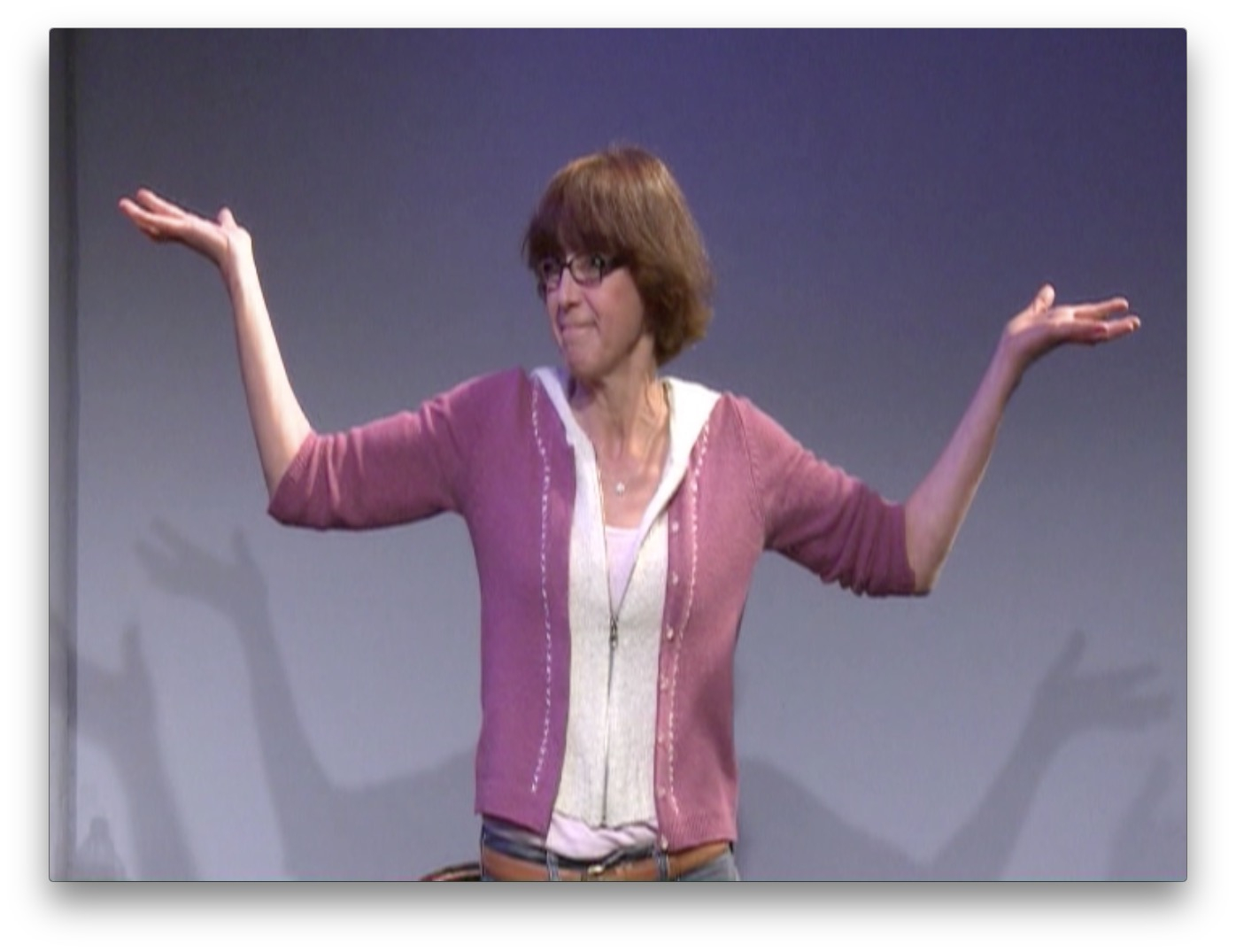

Community Colleges Are Often Ridiculed. This One-Woman Show Prods Us to Value Their Students More.

Levy sat down with Lilith in late July, when she was in the throes of preparing to perform the play at the 20th New York International Fringe Festival. We met immediately following rehearsal and, over glasses of chardonnay, talked about writing, teaching, career shifts and the unexpected curveballs life has thrown our way.

EJB: Was teaching a career goal or was it something you fell into?

RJL: I initially wanted to be an actor. I grew up in Framingham, Massachusetts and went to the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where I studied communications and public speaking and acted in quite a few campus productions. After graduating, I moved to New York City and got roles in several Off-Off Broadway plays. I also became a public speaking instructor at LaGuardia Community College. Later, I got a job at Park West High School in Manhattan where I taught sophomores. I didn’t really know how to reach them, but I met an experienced teacher, Lee, who had been at the school for 18 years. He became my boyfriend and helped me figure out how to approach the students and create meaningful lessons. Unfortunately, after one year I was “excessed,” which is Department of Education-speak for fired, so I started a Master of Fine Arts program in poetry at Brooklyn College. One of my teachers was Allen Ginsburg.

EJB: Were you doing any teaching when you attended Brooklyn College?

RJL: Yes. I actually taught developmental English for the first time when I was there. It was pretty intense, but an administrator in the writing program at Brooklyn College ran weekly study sessions to talk about pedagogy. Thanks to this group and the coursework I took, I started to understand what I was doing. Still, after I finished the graduate program, I moved to Los Angeles to pursue theater. At that point, I still really wanted to be an actor. I lived in LA for seven years, 1992-1999.

EJB: Did you get roles?

RJL: A few. I was, of course, mostly working as a waitress. Then, in 1994 I got a job as an adjunct at the Los Angeles Trade Technical College a public program, teaching “Basic Sentence Writing and Paragraph Building.” It was a developmental class. I started the job the day after the 6.6 Northridge earthquake. I adjuncted there until 1999, when I returned to the east coast.

EJB: Did you like that job?

RJL: Oh my God, yes. I fell in love with the students. They became my friends. They were mostly in their twenties, Black and Latino, and they’d lived very sheltered lives. Most rarely traveled out of their neighborhoods but were excited to be attending school. This was before cellphones and home computers, and they were so eager to learn.

For some of them, I was the first Jew they’d ever met, and they asked lots of questions: Did the Holocaust really happen? Did I celebrate Christmas? Why didn’t I have a foreign accent?

They were curious and open, but they also lived crazy lives. Some were commuting from shelters. Some were single parents, working several jobs to support themselves and their kids. Some were recent immigrants. Some were mentally ill. Some had had friends or relatives who’d been killed by drive-by or random shootings. Some had AIDS. One had been a doctor in her home country.

It was fantastic.

EJB: So why did you leave?

RJL: One day when I was at work in the restaurant, actors John and Sean Astin came in. Somehow we got to talking, and I blurted out, “I’m a teacher.” All of a sudden I realized that I wanted to be back in New York, talking to Lee about student and classroom issues. On top of this, by this point my dad was seriously ill and I was exhausted from juggling so many jobs. I taught in the mornings, waitressed on weekends, and worked as an assistant at a production company every afternoon. I did some acting, too, and continued to audition. It just felt like the right time to return to New York.

EJB: Was that when you decided to become a full-time teacher?

RJL: When I got back to New York I sent my resume to every City University of New York [CUNY] campus. I got a one-year job at York College in Queens in a five-day-a-week basic skills program for women on welfare. I also began as an adjunct at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, teaching from 8:00 to 10:00 PM several nights a week. I eventually became full-time at Kingsborough. I’m there still.

EJB: How did you come to write “This Gonna Be On the Test, Miss?”

RJL: Starting on day one in LA, I’ve taken notes on the things my students say and do. I’d always wanted to write about them because they amaze me. They’re a combination of street-wise and naïve, and the things they come out with are incredible. My first thought was to write a comedy, but I didn’t want to seem like I was making fun of them. I also knew that I wasn’t interested in writing a scholarly essay. I had a lot of ideas and thoughts percolating in my head, so a few years ago, in 2012, I enrolled in “Go Solo,” a workshop led by Matt Hoverman. Matt won an Emmy in 2014 for his outstanding work, and I used the class to write a 20-minute monologue that I performed. The piece has developed a lot since then; after the class ended I worked with Matt privately to turn the sketch into an hour-long production. That’s what I’m presenting at the New York Fringe Festival. I’ve already taken the play to other venues including the D.C.; Portland, Maine; Providence, Rhode Island; and Charm City [Baltimore] Fringe Festivals.

EJB: What do you want audiences to take away from the play?

RJL: When I try to explain what I teach and whom I teach to people outside of New York City, they don’t get it. It’s frustrating. They typically have a negative view of community college students, and it really bothers me. They don’t understand that I can have a 61-year-old grandmother, a veteran, a single-mother of five, a woman with multiple sclerosis, and immigrants from Albania, Burma, China, Congo, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Israel, Mexico, Russia, Sri Lanka, Ukraine and Uzbekistan in one class. These are not pampered kids dancing on club tables or scary kids in gangs.

I feel so privileged to get to be with these students. I want audience members who might never interact with newcomers or low-income people to come away with an appreciation for them. This is a student population that is typically invisible and my goal is to change that, to give them a voice and a presence. I love teaching and I love my students, and I want to show that to as many people as I can. Sure, some students don’t want to be in school or do the work. There’s apathy, entitlement and a lack of preparation for college, but I still see a need to celebrate community colleges and community college students.

EJB: Do you still go on acting auditions?

RJL: No. I don’t have the hustle to secure acting jobs. It’s too unpredictable. I prefer to teach. I continue to write poetry, though, have had some work published and do readings in the City. Speaking of writing, “This Gonna Be On the Test, Miss?” is likely to be my only play. I’m not sure I have it in me to write another, but I’m thinking about ways to get my students to write fables about their lives.

EJB: Anything else you want audiences or readers to know?

RJL: I want people to see that self-transformation is possible. The play outlines how I started out wanting one thing, to be an actor, and got something very different. All told, I want people to know that I’m very happy with the twists and turns my career has taken.