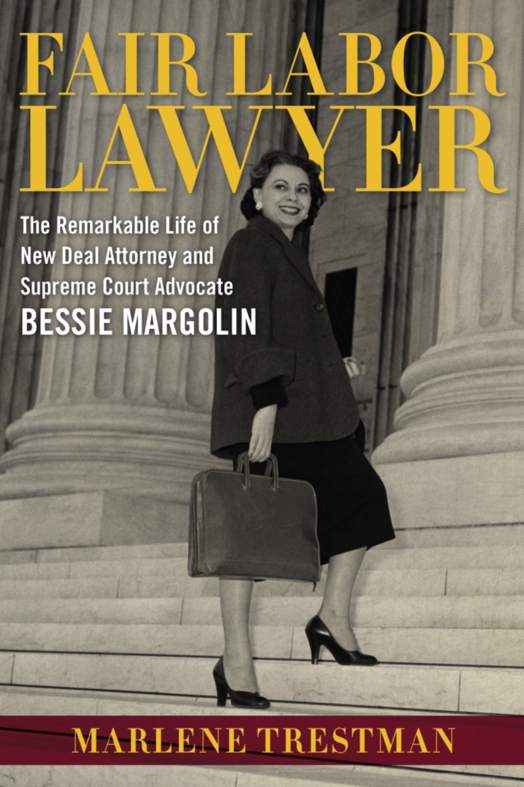

Fair Labor Lawyer: Bessie Margolin’s Journey from New Orleans Orphanage to Supreme Court Advocate

HRN: Do you think Margolin’s non-traditional family background gave her a unique outlook on life?

MT: Margolin’s childhood in the Home, which emphasized citizenship, discipline, education, and social justice, shaped her life, for sure, but perhaps not in the ways most people would think. The Home, particularly during Bessie’s time there, sought to produce self-sufficient and patriotic American Jews who would bring honor to their community, and the community generously invested its finances and passion in caring for these children. In many ways, the Home children fared better—in terms of food, clothing, medical care, and education—than many of their peers in the community. Moreover, Margolin lived in the Home with her siblings. As an adult, she didn’t speak often about her childhood, but when she did she expressed gratitude for the excellent education and the sense of family the Home gave her and, perhaps surprisingly, for allowing her to always feel loved. All of these experiences gave Margolin the confidence and ambition to blaze her own trail, independently.

HRN: You write that Margolin did not realize the severity of gender inequality until later in life. Did her refusal to marry shield her from the expectations that were put on wives and mothers of the time?

MT: Margolin understood as early as law school that she wanted more out of life than an “Mrs.” degree, as evidenced by the way she copied extensive passages from Virginia Woolf’s newly published A Room Of One’s Own in the book she was given by her law school sweetheart before she broke off the relationship. A decade later, she wrote an article in her college sorority alumnae magazine on the need for societal change to prevent women lawyers from being forced to give up their careers to tend to the duties of marriage and motherhood. But perhaps the clearest evidence that Margolin’s refusal to marry was so that she could to retain her career and independence is the way she got her first job with the federal government: her mentor pledged that, if given the job, Margolin would not be “deflected from her career by considerations of marriage.”

HRN: Margolin was raised in a Jewish orphanage, yet you write that she wasn’t religiously observant in her adult life. In what way did Judaism inform her life? Was it merely another hurdle to overcome?

MT: It is true that I could find no indication that Margolin attended synagogue or otherwise adhered to traditional Jewish observances as an adult. As a rare, single woman pursuing a career in the male-dominated world of law, indeed in the most elite circles of legal practice. including at the Supreme Court, further differentiating herself as an observant Jew certainly would have added more obstacles to her career. However, she was drawn to a career marked by the pursuit of social justice, a very powerful tenet of Reform Judaism that was preached in public speeches in the Home by rabbis and other progressive Jewish thought leaders. Moreover, the orphanage itself was born from the biblical mandate to care for widows and orphans—those least able to care for themselves. It is also noteworthy that, as the first-American born daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants, she was drawn to to Nuremberg, where she drafted the rules that established the American Military Tribunals that meted out justice to accused Nazi war criminals. I think these are the examples of how Judaism—especially the principles of tzedek and tikkun olam—profoundly informed her life.

HRN: Margolin campaigned unsuccessfully for a position as a federal judge. What do you think she would have to say about the vacancy left open by the passing of Justice Scalia?

MT: I think there are two ways Margolin would approach the topic. First, as a staunch New Dealer who had received her legal training at Yale during the height of legal realism, and who spent her career skillfully using legislative history to persuade courts how to interpret statutes, I don’t think Margolin would have agreed with many of the late Justice Scalia’s decisions in which he espoused literal readings of statutes (while eschewing legislative history as a guide) and an unchanging view of the Constitution. At the same time, on the issue of choosing his successor, she would be thrilled to know that four accomplished women have now taken their places on the Supreme Court bench, and that gender is no longer an insurmountable obstacle to becoming a judge or a Supreme Court Justice—or a serious candidate for President!

HRN: I noticed you’re working on a second book—one on the New Orleans Jewish Orphans’ Home where Margolin was raised. Why do you feel yourself pulled back to this topic?

MT: While researching Margolin’s childhood in the Home, I was fascinated with what I uncovered about the orphanage’s rich history, from 1885 to its closure in 1946, spanning the Civil War to World War II, during which it nurtured more than 1700 children. Moreover, I was very much aware that, if I had come along two decades earlier, or if the Home had not closed in 1946, I would have been raised there. Since I couldn’t put all of the great things I learned about the Home in Margolin’s biography, I decided to write a second book, the first modern history of the Home. I plan to write the book as a collective biography so that I can share the personal stories and journeys of the people who lived in and ran the Home, and explore the Home’s impact on their lives and their communities.

2 comments on “Fair Labor Lawyer: Bessie Margolin’s Journey from New Orleans Orphanage to Supreme Court Advocate”

Comments are closed.

The U. S. Civil War took place between 1861-1865. As the Civil War ended twenty years before the date given for (presumably) the opening of the “New Orleans’ Jewish Orphans’ Home” (1885), the Orphanage’s history could not be said to span the time from Civil War to World War II.

However, the “Jewish Children’s Home” was in fact founded in 1855 as the “Jewish Orphans’ Home”, and has since undergone several name changes: 1880-1905, “The Association for the Relief of Jewish Widows & Orphans”; 1905-1924, “The Association for the Relief of Jewish Widows & Orphans of New Orleans”; after 1924, “Jewish Children’s Home”; and since 1958 it has operated as the ” Jewish Children’s Home Service”, while retaining the legal name of “Jewish Children’s Home”.

Thanks, Piffle, for your close reading and for catching a typo in the last paragraph. It should have read “orphanage’s rich history from 1855 [not 1885] to its closure in 1946.” The Home, known by various names, was founded in 1855 and thus its operation spanned (i.e., included but was not limited to) the Civil War through World War II. Today, the agency that succeeded the orphanage is known as the Jewish Children’s Regional Service. http://www.jcrs.org