The Very Surprising History of Jewish Women in Comic Books

One essay, for instance, discusses Charlotte Salomon, a graphic artist who was killed in Auschwitz, and whose work was featured on a Lilith cover (Winter 1994-95). After multiple suicides in her family and the increasing threat of Nazism, Salomon had turned to painting her life and surroundings in a way that has shaped modern comics. Author Ariela Freedman describes Salomon’s Leben? oder Theater? Ein Spingespiel (Life, Or Theater?) as what “might be the most powerful Jewish women’s graphic narrative ever drawn and written. But it is almost entirely absent in critical discourse on comics and on graphic narrative. Salomon is frequently left out of genealogies of comics, and until recently, of Holocaust writers.”

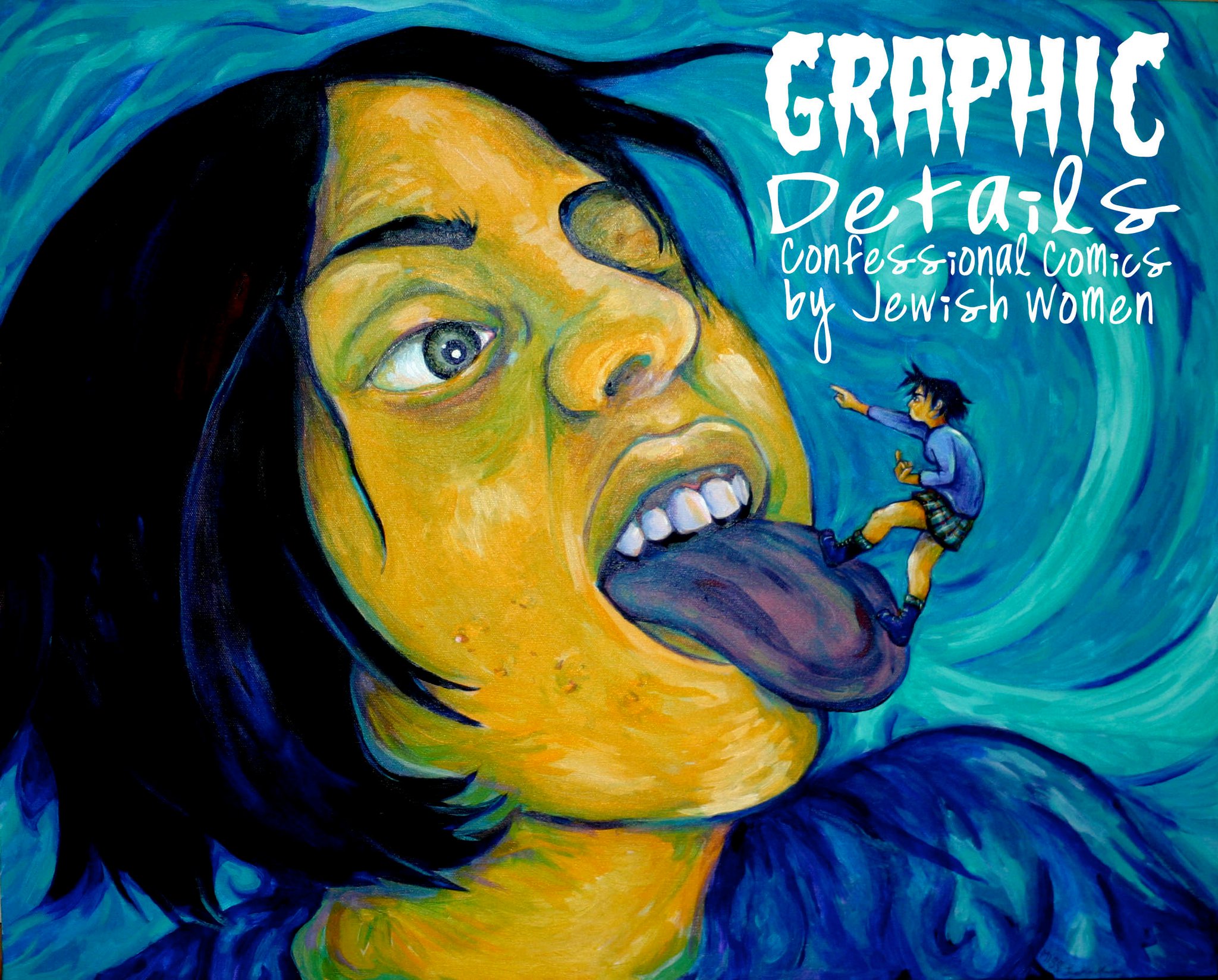

Not all of the creators discussed in this book take on such dramatic subjects. Corinne Pearlman, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Miss Lasko-Gross and Ariel Schrag are all discussed for their scatological and dark humor. Many of the women here want to use comics as a way to show the mostly unspoken parts of life, and by doing so they go against the grain of what people usually think of when they imagine comics. Instead of the typical superhero fighting crime, these comics deal with issues like miscarriages, dating, lesbian romance and self-esteem issues, and they’re always done from the insight of a Jewish woman.

Talking about the power and passion that go with confessional comics, journalist Sarah Jaffe writes in her essay “Telling Their Own Stories”: “Superheroes are impossibly pretty, perfect, every bit of their lives is heightened drama, and for Superman to be ugly he puts on glasses. Indie confessional comics are often purposefully ugly, showing life not only warts and all but with a few extra warts for good measure. Not only am I not a superhero, they say, I am going to lay out all the worst parts of me and dare you to like me anyway.”

The book shows how much female comics creators, turned away by male-dominated publishers, turned to self-publishing or got published by women at smaller ventures. This would allow other women and men to pick up the comics and inspire them to create their own, though these indie comics never got the same attention as mainstream pieces. Graphic Details is a much-needed book both because of its specific information and for the fact it touches on subjects long ignored. While supplying added depth for people who are already fans of the medium, it gives insights to non-fans about why comics are so popular.

In words and pictures, the women in Graphic Details use both drama and humor to show what it’s like to be a woman, what it’s like to be Jewish, and what it’s like to be human and find universal connections in the despair, triumph and love they experience in their lives.

One comment on “The Very Surprising History of Jewish Women in Comic Books”

Comments are closed.