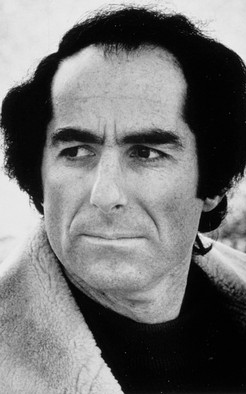

Why I Did Not “Like” Philip Roth’s New York Times Interview

But the plight that Roth has invented for his protagonists, over and over again, is the plight of “masculine power impaired” (as Roth himself explains it). “As I see it,” he explains in this interview, “my focus has never been on masculine power rampant and triumphant but rather on the antithesis: masculine power impaired.”

The concept of “masculine power impaired” is faulted from the beginning—from a feminist perspective, masculine power should be impaired. In his novels, Roth often writes about masculinity impaired by female sexuality; and this reveals something big and troubling about Roth’s attitudes towards women.

Impaired masculinity is a recurring theme in modern Jewish literature—the subject of college seminars and term papers. Scholars such as the historian, Daniel Boyarin have argued that historically, Jewish men have been the emotional victims of the collision of Western conceptions of masculinity with the prototype of the Jewish male scholar. What Roth makes clear in his creation of menacing seductresses, is that women have been as much to blame for Jewish emasculation as tall, athletic, gentile men. Often times in Roth’s novels, the protagonists’ unraveling is the result of an interaction with women such as the brainless model, Mary Jane Reed (“the Monkey”) in Portnoy’s Complaint or the curvaceous, reformed anti-Semitic Pole, Wanda Jane Posseski of Operation Shylock. These women lure the male protagonist, defenseless against his own lust, into further self-destruction and self-loathing.

Some readers of Roth argue that he is of another generation, that he is an 81-year-old man with antiquated views of gender relations, and the public discussion of his misogyny is at this point just as antiquated. But his novels, like any great works of art, have lasting popular appeal. Roth’s fiction portrays humanity (not only manhood) as impaired by ego and passion. And even today, young people continue to read and discuss his novels on social media. While Roth’s views might be antiquated, his books have not lost their resonance with contemporary audiences.

But even while we can appreciate Roth’s writing, we should not dismiss his sexism as harmless and antiquated. We should not make light of Roth’s evasion of Sandstrom’s question about misogyny and the ludicrousness of comparing feminist criticism with McCarthyism. These comments do not diminish the value of his work; but they do help us to contextualize his art within a specific cultural time and place in which sexism was met with greater tolerance.

Feminism does not seek to silence those who struggle with traditional gender roles and feelings of male inadequacy. These issues should be explored in Jewish literature in a way that does not blame and alienate women. Roth belongs to a generation of post-war writers known for their preoccupation with the male ego. This generation defined what we think of as American Jewish literature—but it should not be its lasting legacy.

5 comments on “Why I Did Not “Like” Philip Roth’s New York Times Interview”

Comments are closed.

Excellent and well-balanced response to Roth interview. I, too, am a feminist who appreciates Roth as a writer but who also am continuously disappointed in his inability to portray female characters in all their many dimensions. Thanks for writing this.

I, also a feminist, believe that this article is unfair criticism of a man who is only a product of his time. The women’s movement has slowly progressed, and it is clear that the views of women in literature, films and music have a long way to go, but they are only representative of the time they originated from. This can go the same for racism, communism, socialism, nazism, etc.

As any humanities major will learn, there is no such thing as history, because it will continue to be evaluated, and re-evaluated and re-evaluated as times change. You can only try to understand the point of view in the moment, and note the progressions or failures of these movements. If Philip Roth was publishing such anti-female novels at this time, this would be a cause of concern. Since he is not, it does not take away from the fact that he was and will continue to be a legendary author of his time.

I share many of Shayna’s views and in fact wrote about Roth’s misogyny a long time ago in my book THE JEWISH WOMAN IN AMERICA (Dial Press, 1975; New American Library/Plume, 1976), co-aiuthored with Charlotte Baum and the late, much-missed Paula Hyman. You can still find second-hand copies on Amazon, or check out your library. Or maybe you got a copy for your Bat Mitzvah (lucky girl!).

Sonya Michel

I always thought Roth was making fun of his male characters’ inability to rise up to female power without guilt.

Too much blind association of “Roth” with “Mysogyny” without any quality argumentation to prove such a point. I’ve read every prose word published by Philip Roth and my take is that he is much harder on his male characters than on his female characters. Interviewers continue to ask the author to defend himself against “charges of mysogyny” but never ask those who make those charges to explain themselves. It’s then made worse by claiming that Roth is evasive or lame in his response to said claims. Circular logic. And in any case, art is, it doesn’t mean (especially almost never “means” what critics believe it to mean).