The Poetry of Birthing at Home

Arielle: I will just chime in here to say that Rachel and I have similar backgrounds in this regard, except that I grew up even more deeply in the fold and went further away from it: I, too, went to Hebrew day school from first to eighth grade, and am likewise well-versed in Jewish text and tradition. And, I, too, questioned how feminism and religious Judaism could work together: my mother, for whom this was a life-long struggle, raised me to think about these issues. But unlike Rachel, I was brought up in an observant, Modern Orthodox home, and much of my extended family is Orthodox. And also unlike Rachel, who married a Jewish guy and lives in, one could argue, the most Jewish diasporic neighborhood in the world, I married a non-Jew (a WASP, in fact) and now live in distinctly un-ethnic rural Maine. But—once again, like Rachel!—becoming a mother myself shifted my feelings around Judaism. I dare say that being in an interfaith marriage and living in a place with minimal Jewish community has been good for my sense of commitment to ritual and practice: in the life I’ve chosen, I’ve had to figure out my own way to have a Jewish household and life, and that has meant that I’ve had to be proactive and creative, thinking more about Judaism than I expected to at this point in my life.

Rachel: There are big and little things I have begun to rethink or appreciate about Judaism. I like how the response to hearing someone is pregnant is, “Be’Sha’ah Tova” or “in good time,” rather than “congratulations.” We talk so much in our book about giving up control while at the same time claiming your power (not to mention avoiding early induction!). “In good time” seems much realer and more thoughtful than “congratulations.” After all, not everyone is happy to be pregnant. More significantly, perhaps, I’ve become more and more appreciative of the importance of ritual. At times of transformation we have a great need for ritual. I’m still uncomfortable with many of the orthodox rituals like the mikveh or keeping kosher or covering your hair and yet I find some things—Friday night dinner, rules for mourning, a clear sense of how to provide for and support a new mother—more and more appealing, especially as compared to some of our secular American rituals and rites of passage like hospital gowns, leaving new mothers alone without support, or the customary separation of babies from parents in the hospital. Those seem like terrible rituals.

Specifically, though, you asked about Leah. Being named Rachel I had thought a lot about Rachel from the bible. It’s a very intense story—Jacob’s love for Rachel—and a rather sad story for Leah. After I had children I began to think about these women who had so many children and what that might have been like. I began to understand the burdens and pleasures in a new way. It says in the bible that Leah was given so many children as a comfort for the fact that she was so unloved by Jacob, the names of her first three sons are all about her unhappiness, her affliction of being unloved. Judah is Leah’s fourth son. I had a miscarriage between my second son and my third son. My older sons really chose the name “Judah” for their brother but once I thought about the name I came to love it on so many levels including the way in which it marked a space for the failed pregnancy that is almost entirely invisible and the way in which it made me investigate the parts of myself that are much more like Leah than like Rachel. I could go on and on about this but will leave it there.

Wendy: As a breastfeeding counselor who speaks to postpartum mothers on a daily basis, I was particularly struck by your description of the relationship between birth and the postpartum period:

The culture of fear that surrounds pregnancy and birth has led to a crisis in parenting. So many women believe that their babies almost died. So many women view their infants as fragile, view their bodies as inadequate.

Could you elaborate on the connection between birth and women’s experiences of the “after-birth” period?

Arielle: If a woman is given no agency during her pregnancy or birth process— if her weight and nutrition are taken and recorded without informing her about those things; if she is told her body is too small or her baby too big or her cervix too weak to deliver vaginally; if she is told what to eat, what position to lie in, when to push; if her baby is whisked away from her and given to “experts” immediately after birth so they can “take care of” the baby—well, I think it’s common sense to me to see that this woman’s power and intuition are at enormous risk, and that she might well feel ill-prepared or capable of taking care of her own baby. It seems to me that it’s no coincidence that the increase of intervention at birth has coincided with an increase in the parenting advice industry: there are now hundreds of experts to tell you how to put your baby to sleep, how to wrap it in a blanket, what to buy for it, how to discipline it. In losing our connection to our own abilities to birth, we are losing our connection to our own ability to parent our newborns.

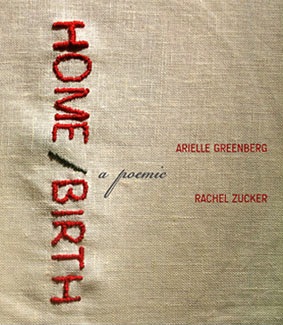

Wendy: One of the most amazing thing about this book is its inventive form. The book begins as a clear enough conversation between the two of you, but often the lines become blurred, and your voices mingle. You also include the voices of other women: women recalling their births, experts in the field, and references to historical birthing pioneers. The book feels like homebirth itself – women helping women, women “holding the space,” as you say, their voices blending and overlapping.

Rachel: Our book is about our friendship as much as it is about birth and feminism. We wanted to work in form that somehow mimicked the very fluid relationship of our friendship—the echoing, constantly interrupted, high satisfying and sometimes difficult conversations about art, family, birth, politics, food, paint colors: about everything.

We’d worked together as editors before but this was our first direct, creative collaboration. Arielle suggested we write about homebirth because she was pregnant and I had just given birth (my first homebirth) and Arielle had recently asked her students to write about a subculture. We began to write back and forth over email and the form grew organically in all directions. We were not interested in writing a kind of thesis/evidence book and wanted the form to feel authentic to our relationship and the way most women we know gather and share information. It’s a kind of storytelling.

Wendy: Many women today are unhappy with the way birth is handled in medical environments, but are scared of birthing outside of it. What would you say to a mother in this situation?

Arielle: First I’d say: educate yourself. Arm yourself with knowledge. Empower yourself. It’s tragic that the majority of parents are making fear-driven choices (and ill-informed ones) around birth. It’s like that slogan about democracy: vote your hopes, not your fears. I’d say plan the birth of your hopes, not your fears. Many studies have shown that out-of-hospital births, attended by skilled practitioners, are as safe if not safer than hospital births, and we quote some of those studies in our book. Our book lists a ton of resources in the back, and there are now so many great ways to find out more about birthing options: from films like The Business of Being Born to books like Jennifer Block’s Pushed to the thousands of amateur homebirth videos and blogs online. I most often recommend Business of Being Born and Pushed, though—and I just realized that both are also made by Jewish women!

3 comments on “The Poetry of Birthing at Home”

Comments are closed.

wonderful wonderful wonderful thank you.

Oh you silly misguided people, how you twist and turn words to fit your ideology. Lilith is the last word you want associated with Birth. Lilith is the one who will take your child from your womb or the crib, that is the essence of Lilith. I understand her place in the world of Feminism, as the first Womban who would not submit. Yet, she is a demon, and to even think of associating a thing like home birth while evoking the name of Lilith is a danger of the highest degree.

While I fully support this article, to be under the guise of a microcosmic aspect of a site called Lilith is ignorance of the highest degree. Shame on you and the harm this shall surely cause.