The Poetry of Birthing at Home

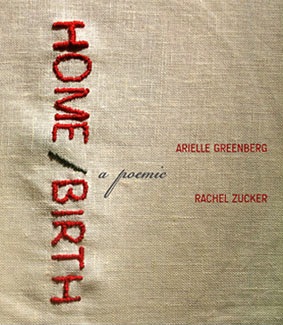

In light of recent news about the high cost of giving birth in the United States, let’s hear from the authors of Home/Birth: A Poemic, which was reviewed in Lilith’s Fall 2011 issue.

Wendy Wisner asks co-authors Rachel Zucker and Arielle Greenberg about the book and their experiences.

Wendy Wisner: Home/Birth: A Poemic was published in 2011, and you both have been reading from it at venues throughout the country. The idea of birthing at home is troublesome and frightening to many people. How have readers/audiences reacted to the book? Has anything surprised you?

Arielle Greenberg: My sense is that most of the people who’ve come so far are already interested in the subject of homebirth, if not rabid about it. So at these readings, there’s a palpable sense of relief, that the unpopular opinion we hold and put forth in this book—that the current birthing system is disempowering and potentially harmful to women and babies, and that women deserve to experience their births in a very different way—has been spoken aloud, and that this community of mothers and midwives and other birth workers who feel this way exist, are visible.

But of course not everyone who has come to our readings has been of this mind, and we’ve been grateful that at each Q&A we’ve held, there have been folks who have questioned and challenged our statements, people who had very different experiences or feelings about their own births or choices. Those disagreements and the discussions that have followed have been some of the most meaningful moments for us.

Another gratifying response has been from people we didn’t expect would read the book: younger women who have not yet decided if or how they want to give birth, poetry readers who would not normally read a book about birth. We’ve heard from people who have changed their minds because of reading our book: changed their minds about how they want to plan their next birth, changed their minds about whether they even want to give birth at all. And this is extremely surprising and extremely gratifying.

Wendy: In the book, Rachel mentions her connection to Leah and Rachel from the Bible, and the special significance of her third child’s name, Judah. How have your Jewish identities influenced your perceptions of birthing, and of women’s relationships to their reproductive cycles?

Rachel Zucker: I grew up in a non-observant home but went to yeshiva from first through eighth grade. I was always interested in the bible stories and midrash and in the study of Talmud, but most of my youth was spent rejecting observant Judaism because I felt it was sexist and patriarchal. I resented the fact that there were different expectations and requirements for men and women and that women were treated as lesser than men. I am still not an observant Jew by any means but my feelings about Judaism have shifted. This shift began, really, during my first pregnancy. I remember being flummoxed as a pregnant feminist about how to make sense of how different I felt, how separate, how vulnerable and strong at once. After years of either being pregnant or nursing I began to feel that it did make sense that I should have different responsibilities and expectations than men had. I had to figure out how to accept this while still maintaining an egalitarian relationship with my husband.

3 comments on “The Poetry of Birthing at Home”

Comments are closed.

wonderful wonderful wonderful thank you.

Oh you silly misguided people, how you twist and turn words to fit your ideology. Lilith is the last word you want associated with Birth. Lilith is the one who will take your child from your womb or the crib, that is the essence of Lilith. I understand her place in the world of Feminism, as the first Womban who would not submit. Yet, she is a demon, and to even think of associating a thing like home birth while evoking the name of Lilith is a danger of the highest degree.

While I fully support this article, to be under the guise of a microcosmic aspect of a site called Lilith is ignorance of the highest degree. Shame on you and the harm this shall surely cause.