What’s a Friend to Do?

Viewers get to test Arendt’s view of Eichmann, because selections of the trial’s black-and-white footage, including shots of him standing in the glass booth plus wrenching survivor testimony, are incorporated, in living color, into the otherwise fictional frames. Arendt insisted to her death that she was only reporting the facts, not offering interpretations or ideas in Eichmann. Most of her male Jewish friends, previously smitten by this magnetic German-Jewish intellect, thought otherwise.

Filmgoers will see the anger of Hans Jonas, her New School colleague, hear references to damning reviews in Partisan Review, and watch as her beloved friend Kurt Blumenfeld turns away from her on his deathbed in Jerusalem. The film collapses Blumenfeld with Gershom Scholem, who famously posed the question that dumbfounded Arendt’s Jewish friends: had she no love for her people in their darkest hour? To which Arendt replied that she loved no nation. She loved only individuals.

Mary McCarthy’s stalwart loyalty to Arendt drives the film. The men, her husband Heinrich Bluecher excepting, have mostly abandoned her, and there’s a pseudo-inquisitorial scene in which a male administration tries to dismiss Arendt from teaching. Sisters in mind, spirit, and body, the McCarthy-Arendt friendship is recreated by director von Trotta as a kind of feminine (not feminist) cocoon.

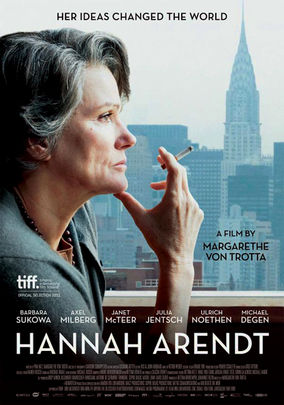

The filmmakers want us to root for Arendt, who – like McCarthy – is portrayed as a deep thinker with a healthy, captivating sensuality. But could Arendt really teach to a mostly male student body, sitting on a table with her attractive legs crossed, a smoke in hand? This scene, as well as the one in which her adoring spouse pats her behind, assumes that Arendt’s sexual agency vindicates the more troubling aspects of her life.

But sex is partly what makes history’s assessment of Arendt’s life so complicated. Her love affair with the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who became a Nazi when he was rector of Freiburg University, plays an important role in the film, even if the script assures us that Bluecher was the man of her life. Yet Arendt’s final speech in the film invokes Heidegger’s view that thinking is life’s highest calling. She insisted that Eichmann’s crime was his “thoughtlessness,” by which she meant his “unthinking.” It’s hard to square that with his integral role in the murder of European Jewry.

The issues raised by Eichmann are still with us today. Although “Hannah Arendt” aspires to be a thinking person’s film, it ultimately opts for hagiography cloaked in a fabulous female friendship. What Jewish feminist worthy of the name cannot support the besieged Arendt?

I, for one.

Nancy Sinkoff is associate professor of Jewish Studies and History at Rutgers University.

Next: A final look at the film festival from Amy Stone.

[The 22nd annual NY Jewish Film Festival ran through Jan. 24 – two weeks of 45 films on the Jewish experience presented by The Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Many will appear on the festival circuits – Jewish and non-Jewish. Check out the films at http://www.thejewishmuseum.org/exhibitions/nyjff2013.]