Reporting back from the New York Jewish Film Festival: Recreating the Past – Incessant Visions: Letters From an Architect

How amazing that Israel television should fund a film in English and that Louise’s voice, a major presence in the film, is not German-accented English but the voice of an American. And it works. (Voice-overs of Eric Mendelsohn by Seann Shaffer and Louise Mendelsohn by Debbie Irwin.)

Weizmann Institute of Science

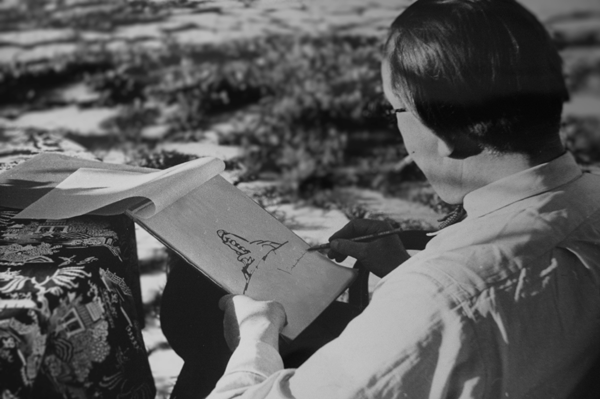

“Incessant Visions” builds on words dug out of the archives preserving Eric Mendelsohn’s 1,500 letters and Louise’s memoir, recreations of his sketching, archival film, interviews, and photographs from the glorious books Mendelsohn made sure immortalized his work, and a score rich with string music. The result is seductive.

It is also the tale of a brilliant architect’s demand for total control. When Louise became involved with another Prussian Jew, the romantic revolutionary poet and playwright Ernest Toller, she thought it was possible to love both men. The result was the extraordinary Modernist glass house Mendelsohn created for her, ironically known as “the open house.” Not exactly a prison, it was an all-consuming responsibility for his wife. He designed everything, right down to the dining room table and chairs, the glassware, the sumptuous floor-length gowns and jewelry she wore for entertaining. Her responsibilities were total – starting with warm potatoes at breakfast.

And she stayed – moving her creative circle of friends to the house, where Albert Einstein played chamber music with her. Louise’s connection to Einstein had already led to one of Mendelsohn’s breakthrough commissions – the Einstein Tower, still standing in Potsdam. It was built to house an observatory to test Einstein’s theory of relativity. Years later, its curved shape kept it standing when shock waves from Allied bombings leveled other buildings. Louise’s connections continued on to enable Erich Mendelsohn’s daring Modernist curved concrete and glass structures to dominate Berlin. She was devoted to this brilliant man.

When his circle, including Einstein and filmmaker Fritz Lang, fled the Nazis for America, Mendelsohn was drawn to Chaim Weizmann’s Zionist dream. His Modernist design for Hadassah Hospital on Mt Scopus was modified by a wealthy Mrs. Jacobs, who insisted on incorporating Eastern elements. Mendelsohn plopped three domes onto the building, which he derisively called “Mrs. Jacobs’ bosom [singular].” His Zionist dream ended when he wasn’t given the entire Mt Scopus project, and he, Louise and daughter immigrated to California. Better known to architecture students than the general public, Mendelsohn was wise to insist on publishing his work in elegant volumes of photographs.

Louise remained the collector of all mentions of his work. In the Mendelsohn granddaughter’s home in Marin County, across the bay from San Francisco, the great “open house” dining room table is compressed into a corner and boxes of clippings fill the shed-like garage.

In Poland, Mendelsohn’s earliest commission, a Jewish cemetery building for preparing the bodies of the dead, is being restored. (It’s amazing that the Jewish community agreed to the extraordinary pyramid-shaped interior covered with brightly painted exotic designs.) But no monument marks the remains of Erich and Louise Mendelsohn. Their ashes were scattered to the winds under the Golden Gate Bridge.

(A DVD of the film is available through www.architectmovie.com/)