Sometimes We Say Hello

Cross-posted with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

The diplomat uses as many words as possible and tries to say nothing; the picture book writer uses as few words as possible and tries to say everything, according to Uri Shulevitz, famed children’s author and illustrator.

The diplomat uses as many words as possible and tries to say nothing; the picture book writer uses as few words as possible and tries to say everything, according to Uri Shulevitz, famed children’s author and illustrator.

Perhaps Shulevitz was following in the footsteps of Rabbi Akiva, who famously said that the essence of the Torah is to love your neighbor like yourself. The rest is commentary. I, too, aspire to write in that tradition of few words.

Judye Groner, editor and co-founder of Karben Books, patiently and graciously corresponded with me about a manuscript I sent her in 2007, Don’t Eat Yet, Don’t Drink Yet. Part of an online writing challenge, the story was inspired by my own children’s experiences at the Forest Hills Jewish Center, in Forest Hills, New York, in the early 1980s, when they were very young.

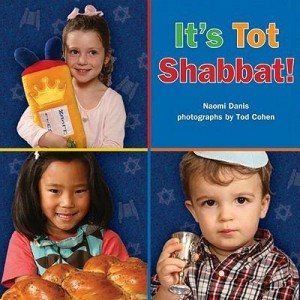

These excerpts from my emails to Judye are perhaps a commentary on (or a davening over) the 233 words that became It’s Tot Shabbat, my picture book, with photos by Tod Cohen, published by Karben in March 2011.

My notes reflect my concern not to make the introduction of religious experience merely the didactic conveying of rules. Like many Jews I am more interested in actions, in what we do or don’t do, and less interested in what people profess to believe. It is in this spirit that I do not mention God in the book. I don’t have a script for that conversation between parent and child, or child and parent, or child and child, certainly not one I comfortably can tell in the voice of a young child.

Every literary endeavor is an attempt to create some order and meaning out of the chaos of our experience, and perhaps the religious enterprise is acting on this same impulse. I wanted to make sure that the gentle but natural chaos of a child’s experience remains, that it isn’t erased by too much order.

Sometimes we say hello

Sometime we feel shy.

Sometimes we feel friendly.

I would like to keep the “Sometimes” in all these instances, so that it shows that sometimes a person feels shy and sometimes friendly, not that there are shy people and there are friendly people.

And although I write “Sometimes we say hello,” I think mostly kids come and don’t say anything at all. Here I am trying to be descriptive and not prescriptive. I imagine many a parent brings a kid into the room and says to the kid “Say hello,” and the kid does not say a word.

I do not want to tell the kids that they have to say hello. I am saying they don’t have to be in any special mood when they go to Shabbat club.

We can do puzzles.

“We can” sounds like the voice of a child, the way a child would have psyched out the situation and figured out the rules: We can do all these things here. (Isn’t that great?) And for me, there is also the association with The Little Engine That Could (“I think I can, I think I can”) and even with Barack Obama’s “Yes we can.”

There is also a subtle hint, for those traditionalists who understand, of activities that are permissible on Shabbat, without being didactic about it. (No drawing, for example.)

Another time

the builders of the tall tower of Babel

didn’t cooperate with each other.

Watch out! Boom!

We all helped put away

the blocks that fell down.

Can a picture show some sense of mischief, or mixed feelings of fear and glee as the tower tumbles? (I know that’s not exactly what happens in Genesis Chapter 11, but I have taken this poetic pedagogical license.)

Once we read how Noah built an ark. We pretended to be the animals who came aboard. I was a porcupine.

Lions or any other animals are fine but I feel strongly about the porcupine. It’s a small, economical, and efficient way to have a bit of emotional depth. The porcupine represents a kid who feels grouchy, prickly, antisocial, not in the mood, irritated, irritating. To add to the diversities that would enhance the book, let’s have at least one of the girls wear a kippah.

And could there be some spilled grape juice on the table or floor? Spilled juice shows in a young child’s terms that even if we are not all perfect there still is a place for us at the table. I think that’s a very important Jewish idea.

One of the joys of writing picture books is imagining – and later hearing from real parents – that my words are the spur or means to convene a quiet, thoughtful, playful, even mini-theatrical moment of interaction between a parent and child.

In It’s Tot Shabbat I wanted to share that it’s good to have Jewish experiences together with other people, to be part of a community. I don’t think anyone goes to shul if they don’t feel it’s a friendly experience. We can make it friendly. It’s good if that friendly feeling starts when we’re young.

I hope this book conveys that a synagogue setting can be a friendly and empowering place for a young child, and for the child’s parents.

Judye Groner likes to say that today’s Jewish grandmother is as likely to serve sushi as chicken soup. That’s why the lollypop lady of my children’s childhood experience who appeared in an earlier draft of this story disappeared by the final version. I had to get rid of the words “My Shabbat has a sweet ending.” But I hope the sweetness comes through in the many other words and in Tod Cohen’s lovely photographs.

© CJ: Voices of Conservative/Masorti Judaism, Summer 2011/5772