Seven-Day Spa

Ethiopian Menstrual Traditions in 21st Century Israel

I spent a year in Israel at an Orthodox women’s yeshiva in Jerusalem; Ethiopian Israeli women were studying there, too, in 2004-05, and one evening they gave a presentation about their heritage. They had painted a mural that depicted a typical Ethiopian village — the kind they’d spent their early childhoods in — and in one corner there was a lone woman sitting cross-legged at the entrance to a hut surrounded by a ring of pebbles. This, it turned out, was a “menstrual impurity hut,” but at the time I didn’t fully understand the implications of that.

Some months later, I sat at a lunch table with a group of Israeli students who happened to be discussing Leviticus 12:1–5 — a set of passages that describes postpartum impurity. The laws in the text had once been part and parcel of everyday Jewish life, but with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE most had lost their relevance. An Ethiopian Israeli friend of mine, Ahuva, sat uncharacteristically silent during the conversation, and after everyone left, she looked around nervously and whispered, “My mother has seven daughters.” At first I had no idea what this meant, but then I put together the mural — that lone, cross-legged Jewish Ethiopian woman — with the verses we’d just been discussing, and asked Ahuva in my halting Hebrew, “So, after giving birth to each daughter, your mother sat outside for 80 days in a… a… ?” I didn’t know the term in Amharic, the language of Ethiopia, but to my surprise Ahuva supplied the Hebrew one: beit niddah — a “house of menstrual ritual impurity.”

“Yes,” she said, and then added quietly, “Seven daughters! And for each she was alone for 80 days! Other women and children brought her food and water, and I guess she rested and spent lots of time with each new baby… but it must have been very lonely, no?” I quickly did the math: Ahuva’s mother had been in a beit niddah for 560 days, or approximately a year and a half. That didn’t include the periods of postpartum impurity following the births of Ahuva’s brothers, nor the seven days that she spent in the beit niddah every month — when she wasn’t pregnant or nursing — from the time she first got her period as a girl until the time she hit menopause.

I knew that Ahuva’s community had arrived in Israel in 1991 during Operation Solomon, and that it shocked them to discover that the Temple in Jerusalem no longer stood! Their practices were based solely on Torah. And while they were overjoyed to be in Israel — they are some of the most reverently patriotic Israelis I have ever met — much of their culture had vanished overnight. Ahuva’s anecdote gave me a glimpse of this.

I had many questions for Ahuva, but it was clear that she had shared a secret and wasn’t open to talking about any of this further. Her brief comments seemed to express both a sense of gratitude — that the beit niddah was not a part of her life — and a certain wistfulness. We cleared our trays and headed to class, but I couldn’t stop thinking about our revelatory conversation.

A year later I returned to Israel expressly to conduct 33 in-depth interviews with Ethiopian women (and male kessim — spiritual leaders — and rabbis) on the topic of Ethiopian Jewish purity laws: how they were practiced; how they had evolved over the last 15 to 20 years; and what, in particular, religious Ethiopian Israeli women in their twenties and thirties thought about them and which ones they actually observed. Women in this cohort had all spent their childhoods in Ethiopia, and then were abruptly separated and plunked down in a radically different world. What determined the lens of my inquiry was, of course, Ahuva — my curiosity about how she would go about reconciling her religious life in Israel with that which had come before.

To understand these young religious women, I first had to talk with their mothers and grandmothers, which I did between sips of coffee and lessons in how to make homemade injera (traditional Ethiopian bread). We spoke for hours, generally with a younger family member translating.

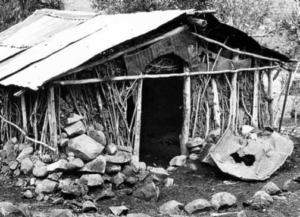

I learned that every Jewish Ethiopian village had at least one beit niddah in which girls and women lived for seven days during menstruation. When a pregnant woman went into labor, she’d go out into a field with midwives, and they’d build her a lean-to where she stayed for one week if she gave birth to a boy, or two weeks if the baby was female. The midwives then brought the woman and newborn to the beit niddah, where they’d stay an additional 33 days if the baby was male or 66 days if female.

In some villages the beit niddah was at the outskirts of town; in others, it was at the center. Travelers could always identify Jewish villages from a distance because they’d spot the beit niddah, which was identical to all the other huts in the village — round shanties of sticks, straw, and mud — except for its border of pebbles (or sometimes a very low wall of stones) that encircled it. Children could come up to the pebble border to sit near their mothers, but they could not come inside, and they were forbidden to touch their mothers. Even touching the stones transmitted impurity. An accidental touch needed to be followed by an immersion in the river, and then a wait until nightfall before returning home.

Some huts could hold up to 20 women; others could accommodate only one or two. If the village was very small, or if a family had its own private beit niddah, a woman could end up alone, but otherwise she’d have company. As one kes told me, “In a larger beit niddah all the women were together, talking with each other. They were alone… together.”

During their days in the beit niddah, women spent their time as they wished, sleeping and relaxing or taking walks in the fields or by the river. They were forbidden to mingle with others in the village and to enter anyone’s home. Food and water were brought to them by other women. In the larger huts, women of all ages chatted and embroidered festive clothing, sharing advice and telling stories. Frequently they left their embroidered pieces in the beit niddah, picking their work up when they next returned. When they were ready to go back into the community, they immersed themselves in the river and washed their garments. After nightfall, they went home.

My informants told me many stories. One recalled an urgent woman once bringing her daughter’s wedding dress to the stone periphery of the beit niddah. “She’s getting married tomorrow and this needs to get embroidered!” she said. There were six women in the beit niddah and they spent the entire day working frantically on the dress — quilting-bee style — in order to meet the deadline.

A kes described for me the celebration of a girl’s first menses. “There was great joy for the family when a girl went to the beit niddah for the first time,” he said. “When she realized that she had gotten her period, she went straight there, and when she returned seven days later, her family made a party with festive food, attended by her relatives and friends.” A woman in her twenties told me, “When a girl got her period for the first time, it was like when a woman gave birth for the first time. Everybody celebrated.”

I began to get a picture of a separate female society. In the beit niddah one got to know other women in the village, as well as reconnect with close friends. Teenage girls sought counsel from older women — either inside the beit niddah or during a walk in the fields. The experience sounded like a week-long Shabbat “with the girls — no boys allowed!” One informant conveyed the atmosphere and bonds among women in the beit niddah through the use of the Hebrew terms “chevrah” and “bayit” — meaning “friendship group” and “home.”

Women’s menstrual rhythms regulated village life in ways profoundly unfamiliar to Westerners, and both the beit niddah and the moving body of water running next to every Ethiopian Jewish village spoke to their centrality. The very public nature of the beit niddah — the shared communal knowledge of every woman’s bodily status — created a comfort with, and even awe towards, women’s bodies. Religious Ethiopian Israeli men, as well as women, talked to me with remarkable ease about menstruation, marital intimacy, and female bodies — precisely because these subjects were such essential features of Ethiopian life. In Western public discourse, by contrast, these same topics arouse considerable discomfort and taboo.

The beit niddah in Israel, needless to say, has undergone transformation. In refugee absorption centers, women awkwardly “translated” the beit niddah into the ends of hallways, and as they moved up into caravans and apartments, they turned closets and balconies into makeshift huts. It is still relatively common for religious Ethiopian Israeli women in their late thirties (and older) to refrain from cooking or entering a kitchen during menstruation. Ironically, the 14-week paid maternity leave in Israel has allowed many women in their twenties (and older) to observe some semblance of the postpartum laws — they remain in their bedrooms for 40 or 80 days. It’s also common for women to refrain from going to synagogue for the requisite seven days, and even my youngest informants — females in their late teens and early twenties — described their discomfort if they prayed at a synagogue (or the Western Wall) while menstruating.

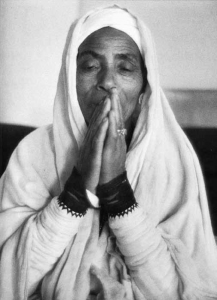

One woman I interviewed, the wife of a kes, has, since the time she arrived in Israel, refused to enter her home while menstruating. Initially, Leah sat outside, even in extreme weather. At some point, government officials spoke with her husband, explaining that he was now in Israel where he could no longer force his wife to do this. The kes pointed out that he had told his wife to come inside, but she refused! Having interviewed Leah, I can attest to her stubbornness — as well as her piety. For her, Judaism is purity and impurity rituals. To compromise or give them up is to become a goy — end of discussion. For Leah, these laws are stated explicitly in the Torah, so follow them she must.

Eventually, the government paid for and built a beit niddah for Leah, and as far as I know it’s the only full-fledged beit niddah in Israel. It’s a building the size of a large shed. It sits adjacent to Leah’s home in Hadera, just north of Tel Aviv.

Leah’s dedication to Ethiopian tradition has rubbed off on her daughters — but they have become religious Israelis who follow rabbinic law. Leah’s married daughter, that is, goes to the mikveh once a month, twelve to fourteen days after the onset of her menses. During this fortnightly period, she and her husband sleep in separate beds and do not touch. After she immerses in the mikveh, they resume intimacy. These rabbinic laws, though, puzzle Leah. How can her daughter cook, let alone be in her house, while menstruating? How can immersion in a mikveh be considered proper? It looks like a bathtub, Leah says, a far cry from a river! She herself will immerse only in the Mediterranean.

The vast majority of young, religious Ethiopian Israelis accept rabbinic law, though one woman I interviewed, Tamar, had a singular understanding of this. She sees her adoption of rabbinic purity laws as additive, rather than as a rupture. For her, rabbinic law is “a continuation of what was in Ethiopia. Everything is one, but in Ethiopia it was stricter. I saw beit niddah customs in Ethiopia,” she says, “but I was too young to experience them.”

Ethiopian Israeli women now in their twenties and thirties stand between two worlds. They are in the process of sifting through their childhood memories, deciding which rituals to keep and which to leave behind. Some abandon their heritage wholesale; others speak Amharic to their children and bake injera regularly. They understand well what it means to be, as the kes put it to me, “alone… together.” Alone in their experience of living between two worlds; together with their parents and grandparents on the one hand and with their Israeli friends and neighbors on the other.

0Tamar is trying to integrate her Ethiopian past with her Israeli present and future. When she gets married, she plans to “walk from both” traditions. She studies the rabbinic laws of menstrual purity at a women’s yeshiva, but when she meets her future husband, she’ll “ask [her] mom and [her] aunt” how to truly observe them.

Sarah Greenberg did her senior thesis at Yale on the changing niddah practices in the Ethiopian Israeli community. She is currently a graduate student in Stern College.