Palestinian Women at the Crossroads of Mideast Peace

When peace broke out last September between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, both sides were unprepared for the dramatic course of events that many had viewed as improbable in this generation. Now, as the political debate moves from the realm of the theoretical to the practical, from the improbable to the possible, Israelis and Palestinians face the difficult task of reconciling national as well as personal dreams and aspirations, fears and apprehensions.

Israel civil-rights activist Leah Shakdiel once described her early encounters with Palestinian women as follows: “I found myself face to face with real, three-dimensional people who had complex identities as women, Palestinians, Moslems, wives, mothers, and who also had national aspirations, like myself. In my family, we were never taught to hate Arabs, but they remained an abstraction and something external to the internal Jewish dramas that were the focal point of my Zionist upbringing. When I see them as real human beings, I must try to reconcile their aspirations and identities with my own.”

Revolutionary changes have taken place in the lives of Palestinian women over the last two decades. These changes have dramatically altered female status and gender roles, giving rise to a women’s movement and a brand of feminism that is fundamentally different from Western feminism.

For Palestinian women, the struggle for liberation has been inextricably bound to the national struggle for self-determination. The inseparability of women’s issues and national concerns, which is so basic for Palestinian activists and problematic for Western feminists, was highlighted, as many will recall, at the 1985 Nairobi Conference of Women, where the United States delegation threatened to walk out in protest against the politicization of the event by the Palestinian delegation. Similar scenes have been repeated often at international women’s gatherings.

The equation between nationalism and feminism among Palestinian women is both ideological and pragmatic. On the ideological level, as Knesset Member Naomi Chazan once observed, “If equality is a principle, then it is universal and must be applied to self-determination for all.” On the practical side, nationalism has provided a legitimate haven for Palestinian women’s activities outside the home. Such activities run counter to the restricted view of female roles that continues to prevail in traditional Arab society. By aligning themselves with the national movement, women have been able to move into the public sphere with relative ease and begin breaking down the barriers that for centuries kept them isolated, dependent and powerless. In a similar way, the donning of the veil (that might appear to be a reversion to tradition and confinement of women) has become a political symbol of national unity that allows women the freedom to move and mingle in the male world while remaining segregated, thereby preserving the all-important family honor.

Palestinian women have been a significant force behind the Intifada (the popular Arab uprising), and there are some who have played a role in peace-oriented activities as well. But having consciously put national interests before any feminist agenda, the question now is, in light of the dramatic events of the past month: Can the gains of Palestinian women be translated into gender equality, female empowerment and productive social roles once the revolution ends? Or will women find themselves, as in other revolutionary movements in Algeria, Cuba and China, relegated to traditional and marginal positions in a post-independence society?

Palestinian educator Dr. Mariam Mar’i says, “Our women are conscious of what happened in other movements, and that awareness will help them avoid making the same mistakes.” She points to Hanan Ashrawi, a Palestinian negotiator at the formal Israeli-Arab peace talks, as a sign of progress and a role model for women. Others, however, like Professor Alice Shalvi, Chair of the Israel Women’s Network, interpret the sea of male faces at the signing ceremony on the White House lawn as a danger sign for Palestinian as well as Jewish women. Rabin’s references to “men of peace” in his speech, and the relative absence of prominent female figures among the various working groups established to pave the road for self-government and economic development in the West Bank and Gaza are only a few of the distressing signals. There are also no women on the executive committee of the Palestine National Council (PNC), which, since the 1988 Declaration of Independence, has acted as a Palestinian government in exile. Says Shalvi, “It is men who are shaping policies that will determine the status and condition of women.

THE PALESTINIAN WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

The beginning of the Palestinian Women’s Movement is traced by scholars and feminist writers to 1978, when a group of middle-class, university-trained activists established the Women’s Work Committee (WWC) in Ramallah. The aim was to create a political organization with a specific women’s agenda. Leaders of the WWC began by organizing women within existing and long-standing charitable societies.

One of the first priorities of the group was to address the condition of young female workers, who represented some 95 percent of the workforce in the West Bank garment workshops, the equivalent of the American sweatshop. These women from refugee camps and villages, prevented from working in factories or at other outside jobs by traditional family values or obligations, were exploited as cheap, readily-available labor for the Palestinian subcontractors who operated the workshops for Israeli companies. According to Phillipa Strum, an American civil liberties activist, who in her 1992 book The Women Are Marching documented the Palestinian feminist movement, many would “work for ten to twelve hours a day…so desperately in need and so unaware of their rights, or afraid to assert them, that they frequently I worked I without knowing how much they [would] be paid.”

When the WWC attempted to persuade women workers to enroll in trade unions, according to Strum, traditionalism again intervened. Husbands and families objected to women’s involvement in gender-integrated groups— even when the men themselves were union members. To circumvent such objections, the WWC leaders set up union centers in their own homes where only women unionists met. Strum estimates that by 1984 some five percent of the over 30,000 female workers had become unionized, compared to about 17 percent of the men.

The next goal of the Committee was to mobilize the masses of women outside the urban areas of the Ramallah- Bethlehem stretch where the majority are educated, upper-middle-class Christians. A leading force in this effort, and the woman most closely associated with the evolution of the Women’s Committees, is Zahira Kamal. Like her Israeli-Palestinian counterpart Mariam Mar’i, Kamal is a teacher of education who emerged as the head of the first committee established in Ramallah. Concerned about the overwhelming majority of wealthy women in the older charitable societies, she persuaded the WWC members to go out to the periphery, to the camps and villages, and learn about the problems of the masses.

The type of grassroots activity initiated by Zahira Kamal has been a critical factor in the emergence of both feminist and national consciousness. Rita Giacaman, Professor of Community Health at Birzeit University, which has produced no small number of Palestinian female activists, says that this kind of activity raised the consciousness not only of the villagers but also of “nice middle-class academics like myself.” Giacaman says it was through her health-related activity in the refugee camps and rural areas that she came to recognize the significance of gender and other feminist issues. This new awareness on the part of the elite led Kamal and others to begin work on a women’s agenda, calling for an improvement in the social and economic status of women as part of the process of liberation from all forms of exploitation.

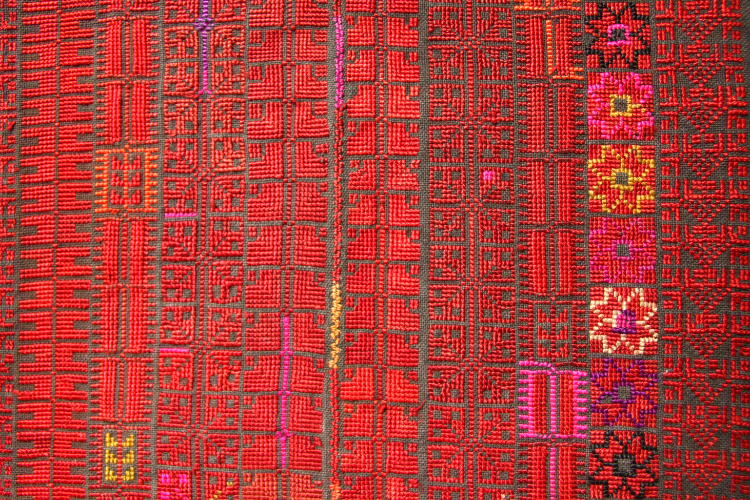

Most of the work of the committees, however, centered around traditionally female functions provided by women for other women. These included childcare and kindergarten programs, community health projects and clinics, literacy campaigns, food production, embroidery and sewing. According to Birzeit University professor Sumaya Farhat- Naser, “Such activities were socially acceptable; they raised women’s consciousness and helped them break the social barriers without provoking men or families.” Her colleague, Islah lad, founder of Women’s Institute at Birzeit, agrees: “The committees represented a school for women. Although they never really developed a social platform, it was a means to achieve political mobilization of the masses. Women became politicized, as they gained self-confidence, speaking ability and a feeling of control over their own lives.”

While some like Kamal and Giacaman saw dangers inherent in a strategy that sidestepped gender issues, most were satisfied with the enormous cultural gains and freedom that allowed women to organize themselves and engage in activities outside their homes. After all, as Phillipa Strum writes, “These were the daughters and granddaughters of Palestinian women who had left their homes only in the company of female relatives, who were in a different room when men came to the house to talk politics or socialize, whom no one saw any point in educating.”

Much like the traditional Israeli women’s organizations, which have been formally connected to Israeli political parties (for example, Na’amat, associated with Labor, and Amit, aligned with the National Religious Party) the Women’s Work Committees were not immune to the political factionalism. Ultimately, members broke away to establish separate committees aligned with specific parties. The first to do so was a group now referred to as the Union of Palestinian Working Women’s Committees (UPWWC) that has been sympathetic to the Palestinian Communist party. This group was followed by the Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees (UPWC) which aligned itself with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. A third group, the Union of Women’s Committees for Social Work (UWCSW), is associated with the PLO.

The original committee, which is now called the Palestine Federation of Women’s Action Committees (PFWAC), has adopted the ideology of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a socialist line compatible with the Committees democratic and grassroots structure. In contrast, the Fatah-aligned UWCSW leans towards capitalism. Although it’s the smallest of the committees, it represents the largest and mainstream sector of society because of its ties to the largest political party. The UWCSW has been slow in responding to gender Issues, reflecting the lack of response on the part of its political leadership as well.

A small group of intellectuals and professional women [see box], including Rita Giacaman, Islah lad and Sumaya Farhat-Naser, has remained politically independent but works closely with all of the committees. “Although I consider myself very political,” says Farhat-Naser, “I feel a duty to remain independent to maintain the trust of everyone.”

THE INTIFADA

The outbreak of the Intifada in December 1987 gave a new impetus to Palestinian women’s activities in the West Bank and to the movement begun in 1978. Women gained high visibility as they joined spontaneous demonstrations, followed mass funerals of those killed in the eruption of violence, and threw themselves at IDF soldiers when they tried to make arrests. Many were themselves imprisoned and interrogated. But rather than bringing dishonor on the women’s families, activities that would previously have been regarded as shameful were treated as heroic, because they were linked to nationalistic ideals and goals.

The process of politicization and socialization of women, begun by the committees in the late ’70s and ’80s, no doubt contributed to the extraordinary female power demonstrated during the Intifada. It also provided a basis and model for a new type of popular committee that emerged during the uprising. These committees provided emergency medical treatment, food and other necessities during prolonged and frequent curfews; they formed education committees to replace schools that were closed by Israeli authorities; established agricultural cooperatives managed by women; and served as welfare societies for families whose wage earners were imprisoned, deported or injured. “Women in the Intifada,” as Mariam Mar’i observed, “filled the vacuum left by the absence of men, as producers, marketers, managers, and so on.”

As the Intifada dragged on, however, with no significant advances toward peace or statehood, the committees appeared to lose momentum and members, while fundamentalism gained ground and families tried to rein in their daughters. Mar’i explains the rise in fundamentalism as a “dramatic answer to a dramatic situation” which she expects is a short-lived response to frustration and despair that will change with new hopes for a solution.

Having developed what many considered a strong social infrastructure, female activists were surprised and disappointed when the bilateral and multilateral peace talks began and it was primarily men who went off to discuss plans and proposals for statehood. Dr. Sumaya Farhat-Naser, as a rare exception, was offered a role in the multilateral talks on environmental issues, but turned down the opportunity in order to stay close to her imprisoned son. “During the Intifada,” she says, “Palestinian women like myself worked hard to build peaceful relations with Israeli women through the Reshet (or “Net”—short for Israel Women’s Peace Net, the Israeli-based organization that has formed a broad coalition with the Women’s Committees). “Since Madrid, we see men going off in their suits with briefcases to talk peace. Where are we?”

Mariam Mar’i echoed a similar feeling: “When we women talked about peace, we were called dangerous, extremists, crazy and God -knows what. When men begin using the same vocabulary and the same logic about the same issue, it is suddenly legitimate. Usually, women do the work and men get the credit. We need to make sure this doesn’t happen in the peace process.”

FIVE PALESTINIAN WOMEN TO KNOW

ZAHIRA KAMAL

Zahira Kamal was born in Jerusalem where her family has lived since the 12 century. She has a degree in physics and, in addition to founding the largest and oldest Women’s Work Committee in Ramallah, has been a supervisor of teachers in training at the UNRWA Women’s Training Center in Ramallah. Kamal has been a key figure in the grassroots activities on the West Bank, often traveling by herself to the back streets of refugee camps and villages to listen to rural, poor and illiterate people concerning their immediate needs. Associated with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, she is one of few women, along with Hanan Ashrawi, to be occasionally visible in the public arena.

SUMAYA FARHAT-NASHER

Educated in Germany, Farhat-Naser began her feminist activity some twenty years ago, through the Birzeit Charitable Society. When the Society held its first election in 1986, she became Vice President. Today, she is involved in Birzeit University’s Community Health Project, administered by women for women in 23 villages.

Farhat-Naser was one of the few women invited to participate in the multilateral peace talks on environmental issues.

MARIAM MAR’I

Born in Acre and educated in the Nazareth Convent, Mariam Mar’i was the first Israeli Arab woman to earn a Ph.D. degree (in 1983 from the University of Michigan).

Recognizing the importance of education for advancing the status of Israeli Arabs, Mar’i founded the Pedagogical Center for Early Childhood and Development of the Arab Child, which she has directed since 1984. She also was the founder, in 1975, of the Acre Arab Women’s Association.

Mar’i has been a leading force in the women’s peace movement, and , in 1988 was a delegate to the New Israel Fund’s USA Coast to Coast Tour for “Women and Co-existence.”

RITA GIACAMAN

Educated in the American University in Beirut, Rita Giacaman is an M.D. and Professor of Community Health at Birzeit University. With fifteen years of involvement in the health movement, she has been a leading force in various women’s research and training centers, combining grassroots activity with research on issues ranging from contraception to domestic violence. Giacaman, in her 40s, and her husband, a physician who heads the Union of Palestinian Medical Relief Committees, recently had their first child.

ISLAH JAD

Educated in Egypt and France, Islah lad is a lecturer in the Cultural Studies Department at Birzeit University. She was one of the founders of the Women’s Affairs and Research Center in Nablus and recently helped establish a Women’s Studies Institute at Birzeit University.

lad is a member of the Technical Committee for Women’s Affairs established by the PLO along with other technical committees after the Madrid Peace Talks.

PALESTINIAN WOMEN TURN TO WOMEN’S ISSUES

Soon after Madrid, Palestinian women began actively preparing themselves for leadership and decision-making roles and the building of an infrastructure for Palestinian statehood. While valuable experience was accrued during the Intifada, it was generally recognized that new kinds of skills would be required for the future. “We need to learn about the law and how to change it, about how to get ourselves elected, about economics,” says Mar’i. “Nobody will give us our rights on a silver platter. Rights are to be taken, not given.”

About a year and half ago, an ad hoc umbrella group of women’s committees, charitable societies, and training and research centers was formed. The move was in response to a number of converging factors, not the least of which, according to Rita Giacaman, were despair, growing impoverishment in the West Bank and Gaza, and concern over the encroachment of fundamentalism. Many had come to acknowledge what a minority of feminists had realized for some time—that without a clear, agreed upon agenda on women’s issues, there could be no real progress towards equal rights and self-determination for women.

The final impetus for explicitly addressing women’s issues came last September with the Palestinian-Israeli Declaration of Principles. Like their Israeli counterparts, Palestinians reacted with confusion and apprehension as well as hope and anticipation. “What one saw through the media,” says Rita Giacaman, “were young people, mostly men, who were either strongly supporting or protesting the events. But there is a silent majority made up of many women who found themselves at a loss. We had become accustomed to making history; now history is being made for us.””

Nonetheless, feminists are clear on one point: the structure of women’s activities and their struggle for equality need no longer be dictated by political interests. Now is the time to worry about democratization, about equal access to education, jobs and decent wages, adequate health care and protection from abusive family members. Although Palestinian women appear to agree that the women’s agenda must no longer be deferred to national concerns, the problems of reaching a consensus on that agenda, and on a strategy, are overwhelming.

North American feminists will recognize the struggle. Palestinian women are torn over the need to serve middle-class interests as well as those of poor, rural women; over the demands for civil marriage and divorce that would benefit the affluent and educated, versus the imperatives of making birth control available to the uneducated masses; over public power and representation in the political arena, versus private power and freedom of choice in the domestic sphere. Some women place emphasis on economic empowerment as the basis for self-determination; others begin with the division of labor in the home as the means for enabling women to be full participating members of society.

VALUING PALESTINIAN DAUGHTERS

The economic stability and political security that people hope will follow from autonomy on the West Bank is expected by some to bring about an inevitable improvement in both the condition of women and in perceptions of their position in society. To begin with, it is argued, birth rates will decrease as children cease to be seen as either political pawns in the battle for demographic superiority or financial assets required to support the family. With the political pressures removed, birth control can be discussed publicly and family planning addressed as a legitimate health issue. Furthermore, if education is compulsory and equal for girls and boys, and women have access to income-generating jobs, greater value will be assigned to bearing and caring for female children than is now the case. Studies have shown that today mothers breast-feed boys longer than girls; that parents are more likely to take sick boys than girls to the hospital; that malnutrition rates are significantly higher among girls; and, not surprisingly, that infant mortality is also higher for females.

Many Palestinian women activists are not willing to leave matters to an inevitable process. They see male superiority entrenched in Arab culture that nothing short of a full-scale battle on several fronts can alter perceptions and overcome centuries of repressive gender roles. Giacaman points out that in many areas Palestinian women are at the very beginning of the consciousness-raising process, when “One doesn’t even realize that private problems are in essence public problems.” Thus, for example, surveys have shown that Palestinian women tend to regard wife-battering as acceptable and within the normative rights of a husband.

Islah lad, currently a member of the Technical Committee for Women’s Affairs, sees three important fronts for action: First, at the grassroots level, raising female consciousness; second, recruiting cadres of professional women to tackle health, education, family law, and mass media—from a gender perspective; finally, preparing and mobilizing women to assume leadership and decision-making positions at all institutional levels.

LINKING ISRAELI AND PALESTINIAN FEMINISTS

In all of these areas, Palestinian women have begun looking toward their Israeli counterparts for guidance and advice as well as for concrete forms of assistance. Leading the way in this area is the Restet, for whom the peace agreement coincides with the inauguration of a no-less-complex joint Palestinian- Israeli venture, the “Link.” The newly formed “Link” will be made up of two centers—one in West Jerusalem, the other in East Jerusalem—each with its own staff and board. According to Reshet Coordinator, Renee-Anne Gutter, the centers will operate both separately and together, with joint activities coordinated by a committee of five Israeli and five Palestinian women, among them Zahira Kamal and Sumaya Farhat-Naser.

The Reshet (which will continue to operate as the political force behind the Link) has begun organizing a series of leadership seminars on topics identified by Palestinian women as high priorities, including political and election strategies. Meanwhile there have been meetings among women from Israeli kibbutzim and the Gaza Strip, and visits of the Reshet to Jericho and to Gaza.

Other Israeli women’s organizations, whose activities among Arab women were formerly restricted to within the so-called green line, have begun developing new strategies in keeping with the new political reality. Na’amat has held a series of consultations with representatives from the UPWWC and other groups. According to Nelly Karkaby, an Israeli Arab from the Galilee who has served as head of the organization’s Arab Women’s Department for many years, “There has been an expressed interest on the part of women from the West Bank and Gaza in learning from our experience in Israeli Arab villages. They want to know about building women’s organizations in general, about fundraising and about developing political leadership.

At its October meeting, the board of the Israel Women’s Network (IWN), chaired by Alice Shalvi, pledged to place joint activities with and for Palestinian women on upcoming agendas. Among the recommendations was the mobilization of Israeli Arab women who have participated in IWN’s political leadership course, as a potential bridge with women from the West Bank and Gaza,

In addition to political campaigning and strategies for getting women elected to governing bodies, the new Palestinian agenda items includes religious and personal status laws; legislation to protect the rights of women and guarantee equal access to opportunities; educational curricula sensitive to gender issues; health care and family planning services that give women control over their bodies and respect their rights to reproductive freedom and choice.

Israeli women continue to be engaged in uphill battles over many of these same issues; they, too, belong to a traditional, and In many respects. Middle Eastern society with a strict dichotomy of gender roles that has effectively blocked their equal participation in public life. Thus, Israeli women are likely to be willing partners In the exchange of Ideas. They stand to learn from the experience of Palestinians who succeeded in mobilizing poor and rural women through grassroots activities, empowering them rather than making them the objects of middle-class programs.

Experience shows that conflict resolution is best achieved through the search for solutions to common problems. Women have shared not only the effects of the prolonged conflict on their families and communities, but the experience of subordination and discrimination as well. As such, they may identify more easily than men with the oppression of others, moving beyond a passive acceptance of existing arrangements toward a vision of a new social order.

Finally, women, who remain the primary caretakers, socializers, and educators of the next generation, have a critical role to play in banishing fear, mistrust, and hatred. According to Mariam Mar’i, who was the first Israeli-Palestinian woman to earn a doctoral degree, “Education and reeducation are areas where we as women can make a unique contribution to the peace process. Rather than belittling our traditional functions, we must instill them with greater empowerment and legitimacy.”

Nonetheless, It remains to be seen whether women will play a role In peacemaking or be pushed aside by the men who faced each other on the battlefield. And perhaps no less significant than the question of women’s contribution to peace is how peace will benefit women. Will it be linked to social justice, equal status and an end to discrimination as universal principles? Or, will feminism and the rights of women remain as secondary and marginal to peace as they have been to war?

Dr. Amy Avgar is a sociologist and free-lance writer She lives in Jerusalem with her husband and three children, the oldest of whom, a son, is currently serving with the Israel Defense Forces.

POSTSCRIPT

On October 21-24, 1993 the Association for Women in Development held a forum in Washington, DC, entitled “Joining Forces to Further Shared Visions.” The conference was attended by over 1,200 women from around the world who shared experiences and strategies to advance and improve their women’s status. The author of this article and Professor Alice Shalvi of the Israel Women’s Network, led a workshop on “Leadership Training as a Strategy for Social Change.”

In contrast to similar gatherings of women from Third World countries, Palestinian and other women from neighboring Arab countries seemed to be magnetically drawn to our session and to the lunch that was organized by region (at which we proudly displayed a sign delegating our table as a Middle East meeting ground.). The kits that we had prepared for the workshop, bearing the logo of the Network, were quickly swept up; and women came primarily to listen rather than argue.

The discussion was not devoid of tension. One Palestinian woman, now living in the USA, told of her family’s wanderings as refugees since 1948. Without missing a beat, Shalvi recalled her own family’s trail from Russia to Germany, to England and finally, Israel. To this, the young woman replied, “We are not responsible for the plight of your family; but you are the cause of our uprooting.”

What distinguished this exchange from others, however, was the ability to move from past injustices to future possibilities; from talk of victimization to potential cooperation. The discussion ended with women excitedly exchanging calling cards, reflecting mutual hope that we might meet again in our home countries.