My Father’s Reckless Abandonment

My father died somewhere in Israel on October 18, 2008; I did not learn of his demise until the following February. His widow did not call or e-mail to tell me. Instead, I found out via the death registry webpage posted by the Social Security Administration, sitting in front of my computer in Brooklyn.

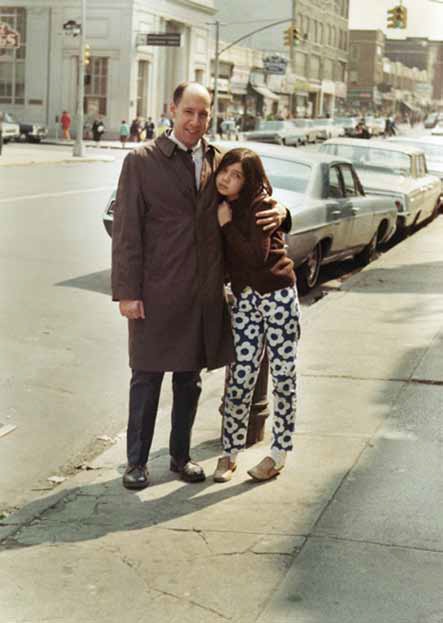

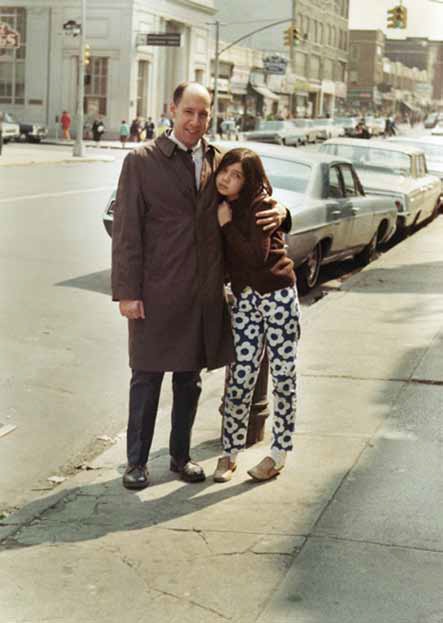

My mother, from whom he was long divorced, had received a terse, cryptic letter from the SSA regarding survivor benefits, so I went online to find out more. A brief search yielded the information I sought — or dreaded — or at least the stark outline of it: name, date of birth, social security number, date of death. I stared at the screen thinking that there had been a mistake, a clerical error of some kind. True, all the variables were in place. My father adopted an unusual spelling of his name, Chayym, the double “y” at its core as distinct and defining as a birthmark. Still I could not absorb the information. How could it be that my father had been dead since the previous fall while I had been utterly unaware, oblivious to his passing? Wouldn’t I have sensed something? Seen or felt a sign? This obliviousness of mine was especially galling. I had been deprived of so many years of my father’s life; now I was deprived of his death as well. I knew that my father and his second wife lived in an apartment in Ra’anana, near Tel Aviv. Had he died there or in a hospital? Suddenly, or after a long illness? What sort of day had it been? What birds chattered in the trees outside his window? Had the air seemed different somehow? The light? I tried to conjure the images and create the context, but both eluded me. I could not understand my father’s death any more than I could understand the apparent ease with which he assumed a new life, shucking off the old one — the one that included my brother and me — so effortlessly, like an unwanted sweater on the first warm day of spring. He was born Hiram Zeldis in Buffalo, New York in 1927. His parents, Simon and Lillian, were divorced and remarried — to each other — several times. Sy owned a liquor store; his wife — inexplicably called Pip — was a large, loud woman who favored fuchsia lipstick and gardenia-laced perfume with a heavy, crushing scent. The family moved to Detroit, where my teenaged father joined Habonim, a Zionist youth group; he met my mother there. After graduation, he spent two years at the University of Michigan — he won the Avery Hopwood award for poetry, a prize once given to W.H. Auden — but in 1948 dropped out of school to go to Israel. Pip could not fathom what urgency propelled her son toward a place filled only with, as she put it, “sand, shit and flies,” but my mother understood, and she followed him halfway around the world. They devoted mind, body and soul to the fledgling nation, living first on a kibbutz in the Negev, where my brother was born in 1952, and then on a moshav, a collective farm, where I was born five years later. My bookish father reinvented himself, tweaking his Hebrew name into a singular moniker with its own unique spelling; the intellectual, aspiring writer became a chalutz, a worker, who spent his days milking cows and his nights toting a gun during shmeerat laylah — night patrol.

But he grew restless, and in 1958, after nine years in Israel, he brought our family to back to America — to Brooklyn. He planned to take a novel-writing seminar at the New School, and so we would remain in the States for a year, two at the most. A year became three, five, ten. Israel, the place that had both called to and shaped him, was left behind. My brother, who was six when we returned, remembered the rough, punishing beauty of the desert, the air, the sky. I recalled nothing; Israel was instead a dream conjured by my father, a myth and fable, a place that was both central to my existence and yet had no concrete reality at all.

It didn’t matter. My father was real enough to fill the gap. The bright sun around which our family revolved, he was witty, he was clever; he was smart, he was probing. He made us laugh and he made us think. He was a poet, a spinner of stories, an enchanter, a man of many quick and nimble words. No matter where he went, he carried in his breast pocket a sheet of 8 ½ by 11 typing paper, neatly folded into thirds. When — on one of our many walks through Prospect Park, the Botanic Gardens and the tree-lined streets of our sprawling, sleepy borough — I stopped to look in a store window or knelt to tie my shoe, I would turn back or look up to find him writing. One column at a time, he covered the sheet in his familiar, tidy print. Once a sheet was completed, he turned it over and repeated the process on the other side. Later, working at night or on weekends, he turned those sheets into typed pages. Nine to five was given over to the job that sustained us all: for 20 or so years, he was the publicity director of Women’s American ORT, a Jewish philanthropic organization that established trade schools in Israel and elsewhere.

I can still see his desk in our apartment on Ocean Parkway, the compact green Olivetti portable typewriter in the center and everything else — stapler, Scotch tape, boxes of paper clips, rubber bands, the cup containing pens and pencils — arrayed around that sleek, über-modernist machine in a constellation of sublime order. When he sat at that desk, I felt that all was right in his world — and in mine.

My father made me feel cherished in ways both great and small. Most memorable, I think, was the way he listened, so closely, so attentively. It was an extraordinary thing, to be listened to so closely by an adult: thrilling, intoxicating, even seductive. I believed the rapport between us was so deep and essential that my being his daughter was its secondary, not chief, feature. He would have chosen to know me — and to love me — no matter who I had been. I was aware of myself as lucky, as blessed. No one had a father like mine, and I never for a moment took him for granted.

And then, all at once, the privileged enchantment that was my girlhood ended.

There was a woman — isn’t there always a woman? — and in 1974 he left my mother for her. Later, we learned that there had been many women; she was only one of a bevy. But she was different in one essential way; she stayed and he followed her, out of his marriage, and into theirs. She did not like me, this woman; she never had. She had been our neighbor in Brooklyn, and I remembered how she had tried to coerce me into inviting her sullen, whiny daughter — my classmate and occasional playmate — to my seventh birthday party. I wouldn’t succumb, and I don’t believe she ever forgot — or forgave. Ten years later, shortly after the wedding, she sat me down on the sofa in their new apartment on East 79th Street and declared, “I didn’t marry your father for a good orgasm.” I still wish I’d had the presence of mind to reply, “Then why did you marry him?” But at 17 I lacked such self-possession, and instead responded by overturning a very large and very full ashtray — I had only recently taken up smoking — onto the floor. I spent the next shame-soaked minutes extracting cigarette butts from her hideous white shag rug. She spoke against me to my father, and accused me of trying to undermine their union. But as appalling as I found her behavior, I do not blame her for what my father did. She might have aided and abetted, but she did not initiate. My father — ever single minded, ever stubborn — had gone ahead and done what he wanted to do, as he always had.

For years, I vainly tried to make sense of what had happened to him, to us. There were two ways I could understand his sudden and radical defection: Either I had committed some heinous crime, for which he was justly punishing me by withdrawing his love. Or else — and this was far worse — I had been fooled into believing that he had ever loved me at all. To think that what I had treasured as true coin was only counterfeit threatened my very being; I felt the betrayal would unravel me, thread by excruciating thread. If I had sinned, there was at least the remote promise of expiation and forgiveness. But to accept that I had been, in effect, hoodwinked — extravagantly, royally, completely — into thinking he loved me made me doubt my ability to distinguish, ever again, love from a score of glib impostors.

In 1989, when my father and his wife moved back to Israel, he did not tell us; we found out only later, through old family friends. Without the Internet, finding him would have been difficult, though not impossible. Still, I didn’t look, because his abandonment was such a calculated and powerful blow, one that left me stunned and reeling. He didn’t wish to hear from me; that was clear. I would not go where I was so patently not wanted.

But although I never saw or spoke to him, I thought of him — with longing, with love, with rage, with sorrow — almost daily, for the next 20 years. When the Internet became as embedded in daily life as the telephone, I Googled him and found his website. There, for any and all to access, was a link that would have led me right to him. Sometimes, I clicked on the address and sat facing a blank page, the cursor pulsing like a small, frantic heart on the white screen. I moved to the subject line. Remember me? I typed in and then deleted it. Fuck you was another possible, though ultimately rejected, alternative.

In the end, I never contacted him, not when my children were born, not when my first novel was published, not the year I turned 50 and he turned 80. I was too proud, too angry, too hurt. But, mostly, I was too afraid: afraid that the father I still loved despite all would say something so lacerating that I would never be able to recover. He was capable of such cruelty; I knew that that now. Knew it and recoiled from it in some instinctual way, like an animal seeking to protect itself from a hurt that is no less lethal for its incomprehensibility.

Then he died, so many thousands of miles away, in a place I had never seen and was unable even to properly imagine. Even in my mind, I could not span the gap between Brooklyn, where I now live, and Israel, the place he had chosen to die. Too wide, too far, too vast for any deathbed reconciliation or reunion of any kind. Instead, there was silence. But that silence was an active one; it listened, it waited, and yes, it secretly hoped. And that silence never stifled the inner voice. The words I miss you and Why did you leave us? may not have been spoken or written, but they were always there, hot and harsh in my mouth, where they will remain now, burning slowly, forever.

Yona Zeldis McDonough is the Fiction Editor of Lilith; her third novel, Breaking the Bank, will be out in September, 2009.