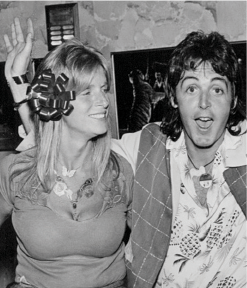

Linda McCartney, Another Tough Woman

Jewish, and just as cool as Yoko

Linda McCartney, unlike Yoko, was white and blonde. Like Yoko, she was hard to put in a box. She is closely identified with the 1960s, during which she took classic photos of rock stars like the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, Janis Joplin, and Bob Dylan, and her talent as a photographer was showcased in several books (the best known is perhaps 1992’s Linda McCartney’s Sixties: Portrait of an Era), as well as in countless galleries. McCartney didn’t court attention by flashing butterfly-wing eyelashes like Pattie Boyd or swizzle-stick dimensions like Twiggy. She didn’t wear a mini anything. She sailed into public consciousness as Paul McCartney’s girlfriend — they married in 1969 — during her Breck Girl phase; then enjoyed a long farm-girl-with-a-mullet phase, when Wings was soaring. She died at 56, in 1998, following her Florence Henderson phase, when she wore gender-negating vests and plain-talked to cameras about her decades-long commitment to animal rights and vegetarianism. At the time of her death, Linda was wealthy in her own right, through her best-selling cookbooks, starting with Linda McCartney’s Home Cooking, and her line of still-going-strong eponymous frozen vegetarian entrées, which, in 1997, had sales in England of more than $56 million.

She was also, though it is almost never mentioned, a Jew. In one of the more sustained looks at the iconic McCartney marriage, Tom Doyle’s book Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 1970s, there is no mention of Linda’s Judaism, though the Wings drummer Denny Seiwell does note that she “had a lot of chutzpah.” But the comment was likely made with no awareness of her background. It wouldn’t be fair to say that Linda hid her Jewishness, though she was generally leery of religion’s divisiveness, but it would be fair to say that her parents’ heavy-duty ambivalence about being Jews complicated her ownership of the badge.

Linda’s mother, Louise Sara Lindner, was from a prominent and moneyed Cleveland family of German Jews. In 1937, she married down when she wed lawyer Leopold Vail Epstein, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants who had raised him in the Bronx. According to Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney, by Howard Sounes, the gregarious Louise was a devoted synagogue-goer as a young woman, but Lee persuaded her that, for their future children’s sake, it would be better to present as less Jewish. Before Linda’s older brother, John, was born, in 1939, the Epsteins became the Eastmans, and the kids got appropriately pareve names. In addition to John and Linda, there were Laura and Louise, the latter named, in a consciously Christian gesture, after Linda’s living mother.

Lee’s stepson Philip Sprayregen told Sounes that one of Lee’s favorite expressions was “Think Yiddish, look British.” “If someone asked [Lee] flat out if he was Jewish, he would admit that he was,” said Sprayregen, “but he would never volunteer that information, and I would say that he was probably glad when people thought otherwise.”

Lee and Louise didn’t completely renounce their heritage. “I think [my parents] tried to have something for Passover once, and we all made fun of it,” Linda told her friend the music journalist Danny Fields in his book Linda McCartney: A Portrait. But the overarching message to the Eastman kids was clear: being Jewish was something that one might not want to advertise.

As a child, Linda was a loner whose favorite pastimes were riding horses and exploring a stream in a vacant lot in her hometown of well-to-do Scarsdale, New York; she was more interested in looking for creatures under rocks than she was in playing with the children of bankers and physicians in the neighborhood. Six months after Linda’s death, Paul told the musician Chrissie Hynde in an interview, “She came from a strata [sic] of society which was really probably American aristocracy and she never really valued it. She thought it had a lot of false values, that there was a lot of social climbing and she never wanted that.” It wouldn’t be a stretch to call Linda’s ebullient mother, Louise, with whom Linda wasn’t close, a socialite.

Lee Eastman specialized in entertainment law and did well (he was “one of the most avid and active art collectors in America,” Christie’s auction house wrote after his death), so renowned artists and musicians were an intrinsic part of Linda’s childhood. The abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning was Lee’s longtime client and friend, and the family occasionally had outings to visit the likes of the painter Franz Kline. Jack Lawrence, a popular songwriter (as well as Lee’s client), wrote the smash-hit single “Linda” for Lee’s eldest daughter in 1946, and it’s hard not to imagine that it gave the little girl a sense of her own importance. One account has it that Lee commissioned the song.

Unlike her three siblings, Linda did wretchedly at school, and Lee scolded her for it. She was the kid who looked out the classroom window instead of paying attention, and since this was in the 1940s and ’50s, there was presumably no consideration that she might have had a learning disability. Because it was inconceivable that someone from a family like hers would not go to college, Linda attended the University of Arizona, in Tucson, figuring that the opportunities for horseback riding would offset the necessity to occasionally hit the books. She was in Arizona on March 1, 1962, when Louise Eastman (who never took the same flights as her husband) went down with American Airlines Flight 1, which crashed in New York’s Jamaica Bay.

Twenty-year-old Linda came home and stayed long enough to attend her mother’s funeral, then escaped back to Arizona and Mel See, her geology-student boyfriend. She became pregnant almost instantly — Heather Louise See was born on December 31, 1962, when Linda was 21. Before Heather’s birth was a marriage, a couple of years later a divorce. Linda and Heather moved to the East Coast in 1965, temporarily parking themselves with Lee, remarried now (and a stepfather) but still living in Scarsdale. He wanted Linda to own the decisions she had made — to drop out of college, to drop out of a marriage — which meant getting a job to support herself and her toddler daughter. Linda rented an apartment on the Upper East Side, which was full of people like the Eastmans: white, wealthy, style-conscious, and Jewish. “Maybe if I’d known the city better when I first started looking,” she told Danny Fields, “I’d have gone downtown.”

Fortunately, Linda had discovered her talent for photography in Arizona, and that paid the bills in New York. It also became her chief artistic outlet for the rest of her life.

Lee didn’t approve of Linda’s lifestyle, which included keeping company with the scrappy-looking rock musicians of the day. “He’s always telling me it’s going to get me in trouble, it’s going to be gone overnight, and I’ll be back being an office intern,” Linda told Fields at the time. (She was briefly a receptionist at Town & Country magazine.) “I was miserable staying where I was, and that state of mind was worse to me than the possibility that this would all be over tomorrow, which of course I never believed. I love what I’m doing, but my family sure isn’t making it easy for me to be who I want to be.”

Lee might not have wanted bohemia to get its psychedelic, smoky clutches on his daughter, but, professionally speaking, artists had been good to him, too.

Linda met Paul at a club while she was on a photography assignment in London, and she did not go on to become the typical rock-and-roll wife. She wasn’t a classic beauty (maybe that was her ancestry manifesting in her longish nose), and she was the rare person whose appearance actually suffered when she wore cosmetics. But her self-assurance was radiant, and Paul defended his decision to include his musically dubious wife in his band Wings by explaining that he needed her there “for my confidence.” He meant for her confidence — she had “bucket-loads of American confidence,” Sounes writes, explaining that that was an important aspect of Paul’s attraction to her.

Linda did, indeed, seem to have a lot of chutzpah. She was the cook who didn’t measure her ingredients, the photographer who knew she had snapped a winning picture before she developed her film. And about Linda’s decision to start a vegetarian-foods company, Paul told Chrissie Hynde that his wife was “the least likely person to ever get into business.” Some of her acquaintances have said that Linda Eastman let it be known that it was her intent to one day marry a rock star. Assuming that’s true, it’s impossible not to be impressed that she made it to the top of the heap.

If there was one facet of her life about which Linda had no business feeling confident, it was when she was performing as part of Wings. She knew she wasn’t much of a keyboard player — fraught rehearsals occasionally brought her to tears — but, again, she was armed with good defenses. Doyle writes this of Linda’s anticipation of bad reviews in the States while touring with Wings: “Initially fearing that she would be eviscerated by the American press, when asked by a Rolling Stone reporter if she had a message for her critics, she replied, ‘My answer is always ‘Fuck off’.”

One of the last songs Linda wrote, when she was undergoing cancer treatments and probably knew that her days were numbered, was “The Light Comes from Within,” in which she goes for broke, singing broadly, “You say I’m simple/You say I’m a hick/You’re fucking no one/You stupid dick.”

While Linda, unlike Lee, might not have been diplomatic, she was, like her father, shrewd. “It wasn’t until [Linda] came along that I realized what was happening to me,” Tom Doyle quotes Paul as saying. “She made me see I was surrounded by con men and leeches.” She had assumed the role in her marriage that her father had in his clients’ lives, but, in a move that would have been uncharacteristic of Lee, she scuppered at least one business opportunity because of her values, putting the kibosh on an almost-signed deal with Volkswagen to sponsor one of Paul’s tours. She felt that the car industry was un-ecological, and she didn’t want the McCartney name linked with it.

Many of the choices that Linda made after she married Paul can be seen as a referendum on her upbringing. Her parents had a big house; she lived happily in a small one on a working farm in Sussex, England, with her husband and four children. (At one point the four kids shared one bedroom.) Linda’s mother had a cook in the household; Linda was the cook in her household, and wrote the daffy song “Cook of the House” about it.

Harvard Law School graduate Lee, in keeping with the Jewish stereotype, was an ardent believer in education, but Linda and Paul enjoyed a steady diet of marijuana that sometimes made them seem a little dull-witted. As for the McCartney kids, they went to local schools in rural England, their peers the children of farmers. And when their parents went on tour, so, too, did the young McCartneys. Doyle quotes Linda as saying that she and Paul had given Heather “the choice of school or coming with us, and she chose the latter. I mean, this is an education in itself, isn’t it? We’re just a gang of musicians touring around.”

But Linda didn’t trample all of Lee’s ideas. George Martin may have been the fifth Beatle, but Lee Eastman was the third McCartney. Lee, with son John’s help, represented Paul during his 1970 lawsuit to dissolve the Beatles, and then stayed on as his business manager. Music publishing was one of Lee’s professional specialties, and he was “thinking Yiddish” when he nudged Paul to invest in something that the musician actually cared about. “Guys and Dolls,” “A Chorus Line,” “Annie,” “Grease”— Lee fattened up the music publishing division at McCartney Productions Limited so significantly that, by the time he died, in 1991, MPL owned 25,000 original compositions. (This is what routinely lands Paul on all those “richest” lists — not just his tours and songwriting royalties.) There was perhaps a whiff of hypocrisy behind Linda and Paul’s periodic denigration of “the suits.”

The besuited Eastmans were instrumental in getting Paul out of the seven-year jail sentence he faced in 1980 after he was caught with marijuana at Narita International Airport in Tokyo, where Wings had flown to start a tour. Philip Sprayregen’s memory of his stepfather’s rage speaks directly to Lee’s injunction to “Think Yiddish, look British.” As Sprayregen told Sounes, elaborating on Lee’s emotional investment in Paul’s becoming knighted, “He went nuts. He was ballistic….He said, ‘My God, my daughter could have been a [lady], and he blew it!’”

Paul was finally awarded knighthood in 1997, a year before Linda died, so she got her British title. Still, she might have been England’s only lady with a bit of the Borscht Belt in her. She was “always one for the joke,” Paul told Chrissie Hynde. “She just had a line for everything.” Again, photography showed Linda at her best. There are some supremely funny pictures of her mugging for someone else’s camera. In the hospital, holding her newborn baby, she squalls in sympathy with little Mary. And in another photo, wearing sunglasses, a black T-shirt, and a bathing suit that introduces hips that have obviously seen childbirth, she holds a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and leans against a car — a perfect, knowing parody of unknowing buffoonery. What other rock wife would have done that?

Or this? After Linda was interviewed in the early 1990s about her vegetarianism, on the English television show This Morning, the hosts got her talking about the pros and cons of fame and its attendant responsibilities. To illustrate her point about the speed with which rabid fans can turn on you, Linda described the scene in Martin Scorsese’s film “The King of Comedy,” in which an elderly, caricatured Jewish woman flags down Jerry Lewis’s character, a beloved Johnny Carson-like talk show host, on a Manhattan street and demands that he speak with her nephew, with whom she’s chatting on a pay telephone. When she’s rebuffed, she says to Lewis’s character — and here Linda turns to the camera — “You should get cancer!” It’s a remarkable split-second embodiment of her birthright: New York Jew.

In his book, Danny Fields notes that in April 1999, a year after Linda died, Paul was known to say about the birth of his first grandchild, Arthur, “He’s a very clever little lad. His mother is Jewish and his father is Christian, so he chose to be born between Passover and Easter.” Writes Fields, “Now, this is astonishing and quite lovely. Mary, Paul and Linda’s daughter and the mother of little Arthur, is of course one-half [sic] Jewish. Yet Paul doesn’t say ‘half,’ he says, ‘His mother is Jewish.’ We now have Paul being more upfront about Linda’s religion than Linda ever was.” As is Stella McCartney, Linda and Paul’s famous fashion-designer daughter, who definitely self-identifies as a Jew.

After Linda died, Paul told various interviewers that he wept for a year and then made himself move on. In 2002, he wed charity campaigner Heather Mills, who shared his humble English origins. After that marriage failed, he turned to a familiar type: a moneyed, Jewish New Yorker. Unlike Linda, Nancy Shevell, whom Paul wed in 2011, isn’t an artist or an activist, and old photos suggest that, again unlike Linda, she had her nose bobbed. Still, Nancy comes across as more Jewish than WASPy-looking Linda ever did. Paul seems smitten.

Maybe he sees a light coming from within.

Nell Beram is a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor and co-author of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies (2013). Her writing has appeared at Salon and Slate and in The Threepenny Review, The Women’s Review of Books, and elsewhere.