Growing Up Cooking—in My Mother’s (and Father’s) Kitchen

For my seventh birthday, I got the best gift I could imagine: my first very own cookbook, Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls. I remember quickly starting to cook my way through the spiral-bound book, although “cooking through” wasn’t a term anyone used in 1959—at least not in Denver.

For my seventh birthday, I got the best gift I could imagine: my first very own cookbook, Betty Crocker’s Cookbook for Boys and Girls. I remember quickly starting to cook my way through the spiral-bound book, although “cooking through” wasn’t a term anyone used in 1959—at least not in Denver.

From Bunny Salad (lettuce leaves on a plate, chilled pear half upside down, two blanched almond ears, raisins for eyes, cinnamon candy nose and a cottage-cheese-ball tail) to Eggs in a Frame (toast cooked in a pan, with the center cut out for a sunny-side up egg), I learned that good food could also look fun to eat. I’m still grateful for the pages of information that taught me how to set the table properly, how to make celery curls and how “A Good Cook Measures Exactly.”

Of course, there were recipes for cakes using Betty Crocker mixes. I mostly ignored these, and produced favorites like gingerbread and molasses crinkle cookies. My sister and two brothers were willing consumers, and my parents more than happy to have me provide treats for the family.

I found I didn’t really need the recipes for dishes like Italian spaghetti, meatloaf or coleslaw. By the time I turned seven, I had been cooking in some form for as long as I could remember. I already had the basics down on those dishes and more. As a young child, I never really thought about cooking; it just seemed natural. Whatever my mother cooked, I watched. Then I helped. By seven, I was proudly making a few things on my own. The memory of me at that age occasionally using our electric stove with the aid of a stepstool, but without any close adult supervision, still surprises me today.

Our family food wasn’t fancy, just tasty and healthy by mid-20th century standards. Sure, we had our share of Jell-O, and we ate beef nearly every night because that’s what my father liked, but other than Friday nights, my mother did not live by a repetitive weekly cycle of dishes like some of my friends’ moms did. Her unwritten formula for our meals was a protein, vegetable, starch and, every night, a fresh salad of iceberg lettuce (all there was in the stores at the time), tomatoes and cucumbers with homemade dressing, soon one of my specialties.

In our house, homemade was best… and also what we could afford. There was no falling back on take-out, or even tv dinners after a long day of work and school. Of course, in keeping with the way things were at the time, it was my mother’s job to make sure there was always enough food in the house for six, including two growing boys. To keep up our supplies meant at least one big trip to the grocery stores every week, usually on Saturday and always with as many coupons as we could clip. I say “stores” in the plural because my mother shopped grocery sales religiously, sometimes stopping at three or four different stores in a weekend to get the best deals.

My mother used the sales to shop in bulk before warehouse shopping was a thing. She was aided in her efforts by cupboards devoted to canned and packaged goods, a full-size refrigerator in the kitchen, full-size freezer in the basement and, eventually, a large chest- style freezer as well. When I think back, I realize there was quite a bit of space dedicated to food in our rather small house! In the refrigerator, lots of fresh fruit, cheeses, deli meats, at least a gallon of milk, fruit juices and always lots of leftovers for a snack or lunch the next day. A freezer full of rock-hard meat, chicken, fish and vegetables, which my parents realized were healthier than canned when fresh wasn’t available. No wonder that today, even with my son at college leaving me as a household of one most of the year, my refrigerator, freezer and food cupboards are nearly always full. It’s just the way it’s supposed to be.

In between major shopping trips, and while various children waited in the car, my mother often needed to stop on the way home for “just a loaf of bread” or “some milk,” which always turned into two or three large brown bags stuffed full of groceries I didn’t realize were missing from our house. Astounding and frustrating at the time, but an admirable accomplishment from my perspective, now.

Jewish food was always a part of our regular family repertoire, and even more important for holidays. At Passover we cleaned the kitchen of hametz, the forbidden leavened foods, putting all the non-perishables in many grocery bags we stored in the basement for those eight days. Then we washed the refrigerator and all the cupboards of any remnants. The day before the first seder, while my brothers grated horseradish by hand—outside, thank you very much—I was the master haroset maker, chopping large quantities of apples and nuts in a large wooden bowl with a big red-handled chopping blade held tightly in my fist until the pieces met my exacting standards for “perfect size.” Most holidays included my mom’s brisket, my father’s turkey with matzah farfel stuffing and my own citrusy sponge cake.

Although we belonged to a large Reform temple, with its looser sense of traditional Judaism, my parents were strict about Friday night dinner—a family night with the blessings over candles, wine and challah (store-bought). My father was not fond of chicken unless barbequed, so our standard Shabbat dinner was roast beef. Around age 9 or 10, I became responsible for going down to the freezer every Friday morning before school to retrieve a roast in white butcher paper. Back upstairs, I put the frozen chunk on a rack in the roasting pan and seasoned it heavily on every side with garlic powder, paprika, salt and pepper. I never measured, because none of my family ever did except when baking. I added about a cup of water to the bottom of the pan before sliding it into the oven, where it would spend the day defrosting. Then, through the magic of time bake, the oven would cook the roast to medium-rare perfection just as it was time for dinner…providing I had set it correctly, which I am relieved to say was nearly always the case.

For Jewish holidays, my mother made an admirable brisket, usually with a packet of onion soup, tomato paste, garlic and pepper, with lots of sliced onions and carrots added. There was chicken soup with abundant vegetables and matzah balls, schmaltz (rendered chicken fat), chopped liver, potato kugel and a delicious yet impressively easy noodle kugel that is still a favorite today. When my little Russian grandmother, Gussie Fleishman (of blessed memory), came to live with us for my junior high years, a lot of boiled beef tongue and broiled sweetbread (always just brains to me) started appearing. No way I wanted to learn to cook those, much less eat them! I am convinced that some of that food is part of the reason I stopped eating meat over four decades ago.

At this point, I need to admit that I am the product of a mixed marriage, the union of an Ashkenazi woman and a Sephardi man. My grandparents were from Russia’s Pale of Settlement or the Ottoman Empire. They spoke Yiddish or Ladino. So some of our Jewish food was a bit different from that of every other Jew I knew in Denver, and it went well beyond my parents’ annual argument over whether or not we could eat rice on Passover.

Unlike my friends’ fathers, whose sole contribution to family food was the occasional barbeque, my father cooked, and cooked well. Some Sundays, Poppi would labor lovingly over big pots of lentil soup that started with browning a substantial beef bone and lots of onions, or fasülya, another beef-broth soup with chickpeas, sometimes with green beans added. From him came my love of baklava (which I learned to make for him), feta, Kalamata olives and yaprakas, as we called the stuffed grape leaves based on his mother’s roots in what is now Macedonia. We always made yaprakas from scratch, of course, with par-cooked rice, ground beef and spices rolled into grape leaves and cooked in a very lemony sauce. I learned to make the baklava from scratch on my own, in part because it made my father so happy and me very proud of myself. I also made Passover sponge cakes all year round—Poppi’s absolute favorite, especially when accompanied with a cup of strong coffee. Decades later I discovered that sponge cake, known as pan de Espagna, was a favorite of the medieval Jews of Spain or, as we referred to them, our ancestors.

Even though my father had some strong opinions about male vs. female work roles around the house, in the kitchen he was far more egalitarian. As a result, both my brothers became good cooks and my son, too—a heritage important for me to pass on.

While my mother worried more about food as part of our health and survival, Poppi savored food, enjoying the cooking process as he fantasized about opening a restaurant “some day.” He never did open his restaurant, but the truth is that my father was a better cook than my mother, more adept at using ingredients with an innate sense of seasoning and taste. I never said this to either of them, but I think my mom knew it was true even though the kitchen remained primarily her domain until, over time, it became mine.

By the time I was 10, I was in charge of making the brown-bag school lunches for my brothers and me, which meant less pimento loaf and bologna, more tuna fish and PBJ. Each evening I made the salad and dressing and often other parts of the meal. I did the Friday night roast ritual and baked when I wanted to, usually from my Betty Crocker cookbook. I enjoyed cooking, and in those years did it mostly on my terms.

Then, in 1963, my mother went to work full-time.

The only other moms I’d known who worked did it mostly part-time in a family business. Looking back, I wish I could say this was an act of early-onset feminism, but it was really desperation. My family needed the money after my father was swindled in a business deal. The guy he trusted went to jail, and we went broke. Worse yet, my father couldn’t find another job because, approaching his mid-40s, he was “too old” for most companies to invest in him.

So my mother, still in her 30s and with great secretarial skills, started going to work downtown every day for the Courts of the City and County of Denver, even with four children ages 3 to 14. It seems this meant the biggest changes for my little sister, who had to start going to an all-day preschool at the local Jewish Community Center, and for me, the second oldest child and the first girl. I became the one responsible for getting the whole dinner on the table for the six of us every weeknight. Suddenly there was less pleasure and more pressure in cooking, even as I got better and better at it with so much experience. By seventh grade, the next year, I started to resent being stuck coming home quickly after school every day to clean up dishes left from breakfast, set the table and fix those healthy, tasty dinners. Lots of other kids would walk home with friends to hang out, or stop in the local drugstore for a soda, ice cream or candy.

At some time during my teen years, I had a decision to make, although it wasn’t conscious at the time. I could either resent having to cook so much, having to feed and care for my family in a sort of “mini-mom” role, or I could embrace it. While I struggled with other parts of this role, cooking had already become part of my life as a form of creative expression and source of satisfaction. So, I kept cooking and, mostly, kept finding pleasure in it. After a family trip to Los Angeles one summer, I added rice pilaf to our Shabbat dinners, which my Poppi loved. I dressed up frozen vegetables with mushrooms, one of my favorites, or sautéed onions, chopped nuts, dill, mint and other touches. When my father turned 60, I cooked most of the birthday dinner we had at our house for many of his friends. The menu included homemade yaprakas, baklava and a new recipe for a Turkish chicken dish that he actually enjoyed.

Susan Barocas at an Obama White House seder. She was guest chef for the seders from 2014-2016.

Just recently, I realized that there developed a kind of Torah around my family’s food—stories and lessons learned about how you care for people by how and what you feed them: Make real food from scratch. Value good ingredients. Take time to make it right. Spices and herbs, especially garlic, are good for our tastes and our spirits. Always have enough food in the house to feed the family three home-cooked meals a day, even if snowed in for a week. And, like Abraham, welcome everyone who stops by, no matter how unexpectedly, with a good, home-cooked meal and good, strong coffee.

I have kept cooking over the years for family and friends including fixing home-cooked dinners for my son nearly every night after a long day of work. Even now that he is at college, I cook for myself. As always, it nourishes body and spirit.

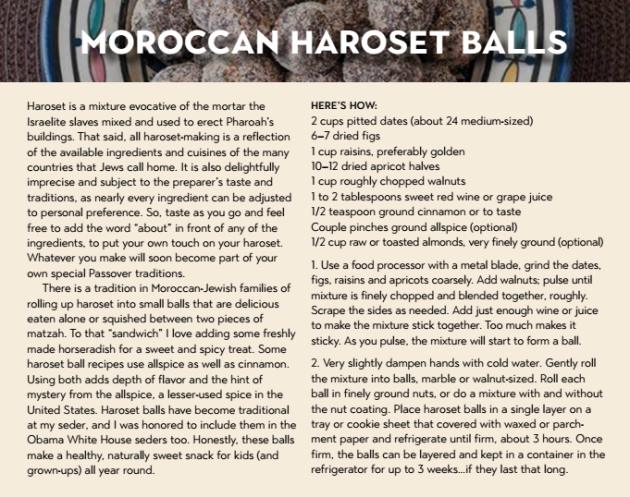

For the past several years, my work has centered more and more around food—as a teacher, writer, chef and caterer. Cooking—and feeding lots of people—brings me incredible and deep pleasure. It also resulted in one of the high points of my life: serving as the guest chef for the Obamas’ White House Seders from 2014–2016. Each of those years, standing in the surprisingly small, beautifully organized kitchen, whether making Moroccan haroset balls or herb-filled gefilte fish, I felt the presence of my parents and my ancestors. They were, and are, always in the kitchen with me.

Nearly 58 years and over 200 cookbooks later, I still have that first one. Pages have fallen out. Some are stapled together. Scraps of paper mark recipes I used while raising my now 20-year-old son. Gingerbread was one of his favorites, too. A few pages are missing, including, sadly, the one with the ingredients for the molasses crinkle cookies. Still, the book is a treasure to me. I look at the inside cover, where I wrote my name in my loopy cursive, and remember so much of my early life in the kitchen.

Susan Barocas is a writer, chef, teacher and documentary filmmaker who was the founding director of the Jewish Food Experience. This essay is dedicated to her parents, Shirley and David Barocas, both of blessed memory.