Dear Editor

No one sees him come in.

Shabbat candles flicker on the table. The braid of challah is almost eaten. Remnants of fruit salad lie in plates, and glasses are empty. Conversation also flickers, sporadic, yet comfortable. It is late.

Newly divorced, I am wondering whether I can remake myself as an observant Jew.

Most of these people are strangers to me. Mark, whom I’d briefly dated after my divorce, is visiting after a year in Israel. If I hosted a Shabbat meal for him, he would invite friends who’d each bring a dish, and we would celebrate.

So, I wear a kerchief around my head as I had seen my grandmother do, and light candles. But I need help with the prayer. The heavy brooding eye of the man seated opposite catches my attention. Asher Kidushanu, he prompts, and I go on, haltingly, L’hadlik neyr shel Shabbat. Smiling my gratitude to him over the lit candles, I feel myself almost become “the woman of the house.” Rolling his head back, stroking his ample beard with clean, thin fingers, he says Kiddush.

My daughters seem mesmerized by the ritual. I’m glad they’re seeing it. I never do it, the center of the tradition, and I remember the small candlelit Brooklyn apartment, my grandfather tall and dignified as he davens from the Siddur. Borey Pri ha-gafen. Everyone drinks wine. One of Mark’s friends says the Motzi over the challah. Everyone eats.

I had phoned nick that morning to confirm our date for Saturday night. He’s working at the Farmworker’s Association, and I haven’t seen him for 10 days. That’s long — longer than we’ve ever missed since I met him at that art class he taught last fall. We’d cuddled near cozy wood fires all winter, had taken long walks in spring. Late in June, he’d helped me dig up compost and plant the tomato seedlings I’d grown indoors.

It had been magical: the sun warm, the earth rich, the infant plants sturdy as a chorus line kicking in the breeze. Then suddenly, eight weeks ago, he’d brought a stack of his paintings to store in my basement. Giving up job, apartment, and the artwork I so loved, he’d decided to commit to labor organizing. Migrant workers. 80 hours a week, sleeping in the back room of headquarters’ cadre. Our time together narrowed to a trickle.

“I’ve thought about it,” he’d explained. “You think I can draw elegant ads to make businessmen rich while migrants starve 10 miles away?” His blue eyes were clear as he shrugged his shoulders. “I have to do this.”

My father had been an organizer back in the 1930s, a worker for peace in Vietnam, so in a way I’m primed for Nick’s purity, his commitment. But why the fanaticism? Why 16 hours a day? Why not four hours a day and part-time art jobs? To give up all comfort, to stop painting, to jeopardize our relationship?

Sure enough, he has forgotten Saturday. He has to work. The movement just started to organize nursery workers in the west end of Suffolk County. He can’t get away at all.

“OK, see you, Nick,” I said, and I can hear something clipped and harsh in my voice.

“Wait, wait. What about tonight? After 11. Can I come over?”

“I have six people coming for dinner.”

“When will they leave?”

“About 11. But it’ll be too much. I don’t want so much at once.”

“Let me come and just be with you. It’s been so long. I miss you. Listen, I was made head of the Benefits Committee. That’s why things are so screwed up.”

I am weary of it. Two months of hunger. Still, his voice is low and calm, and there are spaces between the words that mean that he is capable of listening. I know that about him. He can hear, understand. “OK, Nick,” I say. “Come over when you can.”

But I pray that they’ll be gone before he comes. He might be barefoot, ragged, sick. He might be wearing a wool sweater and pants three sizes too big, or a shirt missing half its buttons, and pants not beginning to cover his ankles. It depends on what came into the office donation box when he decides on a change of clothes. And there’s his dog. Brown-spotted white with too small a head and a chunky body, Nick takes him everywhere.

Looking around the table, I wonder what Nick would think of these people. Their projects are confined to Jewish old age homes or the Jewish poor. To Nick, their ideas would probably seem racist, narrow.

But the values chaining us to the flame-centered table have wrought a kind of magic. The Sabbath has been welcomed with joy, its presence palpable.

One guest, a Hillel director, talks about communities that were formed in the ’60s. Work, learn, pray, even live together. People listen, waves of talk washing gently over plates of food. As hostess, I get up many times to bring ice cubes, orange juice, mint tea, slices of lemon. And the heavy-lidded eyes and the gruff beard of the pale man who gave me the Hebrew prayer, Moshe, a calligrapher, follow me, making me feel demure and quiet, until the kerchief on my head seems a symbol of religious married life. I feel like part of a ballet. It’s as if I am dancing my Orthodox grandmother’s role and for the moment don’t ask more than to serve. I would pour water over my husband’s hands before eating, and hold the towel he would use to dry. All such rituals had been decided centuries ago, and were written in the Law. It was just a matter of deciding to follow it. Was that what I needed now? With two daughters to raise, where should I look? Was it possible that with an observant husband I could be happy?

“Some of those communities survive, and are thriving,” says the Hillel director. “Moshe, you belong to one, don’t you?”

I turn to look at him. “You belong to one?”

“We don’t live together as a group. But we’re close.”

“Where do you meet?” I ask.

“Remind me before I leave. I’ll give you the name,” he says. “It’s a good way to find people with similar values.”

And now Mark is talking about the Bintel Brief, the bundle of letters. The early Jewish immigrants to America, often with family still in Eastern Europe, had been transplanted to a civilization with different laws and customs. In the same way that troubled people would write to “Dear Abby,” so did the confused immigrants appeal to the editor of the Jewish Daily Forward. Someone had compiled both letters and the editor’s answers. “Dear Editor,” they all began. “Tell me, help me, what should I do?”

“They published unedited letters,” says Mark. “The conflicts are interesting.”

“Give me an example.”

“They’re so varied, you really have to get the book,” he says. “For example, “Dear Editor, in Russia I was engaged to a man whom I loved. He emigrated to America three years ago, and told me he would send me money for passage. I didn’t hear from him, but my family gave me money for the trip. Now I find that he is married, and had a child. What can I do?”

The woman on my right had read them too. “Here’s another typical letter,” she offers. “Dear Editor, My parents are Orthodox, from Poland. We came to this country eight years ago. I recently met a Jewish man whom I have fallen in love with. But he is a non-religious Communist. My parents have forbidden me to see him. What should I do?”

“My God,” I cry, my fist forming involuntarily and banging the table so that the few remaining berries on my fruit plate jump into new patterns. “That sounds like my mother! From an Orthodox home, and my father was a red-haired Communist who had no use for tradition. She’s still guilty for having married him. Isn’t that incredible?”

“There were many like her,” Mark says. The bearded man opposite nods slowly, his cheeks sallow, morose. I lower my eyes. Why had I yelled? Would an observant wife have yelled? The kerchief feels heavy on my head. I raise my arms to fix it, pushing the straying hairs back underneath.

And then the meal ends. My guests seem tired. Mark had a tough week, and was ready for the Shabbat break. They sit a while longer, absently talking about leaving, about the left-over wine (“You take it. Believe me, I won’t use it.”), about how delicious my casserole had been, and the fruit salad, half the bowl is left. Good, I think, reaching for a bit more wine. They’ll be gone before Nick comes. Thank God. My younger daughter has fallen asleep. I feel dignified and maternal as I kiss my older girl good night.

And suddenly, there is a dog in the living room. People rise from the table, confused.

“How did it get in here?” a woman asks.

“Your cats!” a man says. “What will happen when they see a dog?”

“That’s Spot,” Lisa says, sleepily. “He was in fights.”

“You know the dog?” Mark asks me. “Whose dog is it?”

Spot patters over to the cat’s food and with great equanimity begins to tongue up and crunch the brown stars he finds there.

As I put the wine bottle back in the center of the table, the candle flame flickers painfully near my arm. And then, there is Nick, younger than any adult in the room, wearing jeans and a crazy magenta shirt too small for his broad, beautiful body. The open, disarmed faces round the table look at him in disbelief, shuffling chairs to get away from the confined dining area.

The man with the heavy eyelids looks at me in a strange, sinister way, and smiles.

“This is Nick,” I stutter, “and this is Mark, and Moshe, and Rich, and Ruth, and, I’m sorry, I’ve forgotten your name.” Nick stands there, uncomfortable, as everyone says a polite hello, and no one knows what else to say or do. They get up and push chairs away and their feet move slowly and erratically toward the front steps like iron filings drawn towards a magnet.

“Moshe, bring the pot that the fruit salad was in,” calls Rich, and Moshe comes into the kitchen and look at me, his heavy eyes sardonic: the demure Jewish housewife.

“Take it with you,” I beg. “You can enjoy it tomorrow.”

“No,” he insists. “We made it for you. Your girls will eat it.” As he transfers it into a bowl on the sink, he looks at me again through those heavy, mocking lids, and he washes the pot.

“Goodbye,” they are calling, “Thank you, it was beautiful, thank you for having us.” My feet bare beneath the long blue dress that I wear on holidays, I kiss Mark on the cheek and wave to the others as they file through the door.

Nick has disappeared. I clean up hurriedly, gruffly. I pile plates into the sink and pick up glasses four at a time. What right had he? Why did I agree? 11:30? The whole mood is ruined. I feel like punching, like hitting. All week he doesn’t call, and then he comes at 11:30. Living a lie.

And where is he now?

Walking through the cool night, I realize that the kerchief has slipped and is hanging down at the back of my neck. I pull it off.

I find him and the dog at the far end of the garden. He is stretched out in the long grass just beyond the ripening tomatoes. As I pass, I inhale their pungent, acrid breath. They should be picked, I think. Some are already split, and ooze the serum of readiness.

And then I am beside him, looking down, waiting.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I stayed in my car for 20 minutes. I was afraid I would fall asleep and not get to see you after all. I figured that maybe if they were friends of yours, you wouldn’t mind me meeting them.”

“If you walk in after 11, you have to be either my husband or my lover, right?” I say, my voice still harsh from the clatter of the cups and the clank of silver against the porcelain sink.

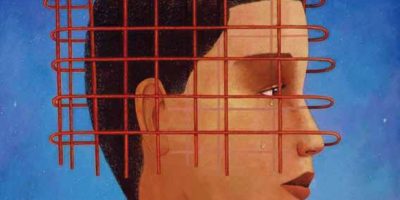

Suddenly the impossibility of a relationship with a man like Nick in the world I’d grown up in, the world I had known, washes over me as I sit down, clenching the long grass that is mostly weeds because I don’t care about such things. But I care about some things, I think. I want someone to pull with me. I don’t want to live in the hurricane of revolution. The words knock about in my chest, unsure of whether to come out.

“Why didn’t you stay in the house?” I ask.

“I could feel how angry you were,” he says quietly. “I thought maybe you were interested in one of those men.”

Intuition. Honesty. And I draw closer, looking at him, drinking in the blue sincerity that looks up at me like a stamp that you paste on letters to the future. He won’t change, I think. This is who he is. There is this wonderfully intense and quiet depth for the moments he is with me, this collapsing of space, this momentary feeling of union—and then, nothing. No building. No continuity. No “getting ahead” in any traditional sense. No guarantee of scheduled time in any regular way. And I remember the Bintel Brief. To which editor could I write? What expert would understand how still my heart is when near him, and how full?

“I wonder if anyone ever had this kind of problem before,” I say, although he can have no idea what I’m referring to. He wasn’t at the dinner and didn’t hear.

As if in answer, he carefully presents me with one of our ripe tomatoes. Round, red, it is the perfect size for my outstretched hand.

Marcia Slatkin, former teacher and farmer, now plays cello, takes photos, and writes poetry, fiction and plays. Her books include I Kidnap My Mother (Finishing Line Press, 2005) and A Woman Milking (Word Press, 2006). www.marciaslatkin.com