Barbie’s Mom Speaks—An Interview with Ruth Handler

Teen Talk Barbie was the victim of grassroots political action in toy stores on both coasts this past holiday season, reports the New York Times. Performance artists bought Teen Talk Barbie and a boy doll of equally classic lineage, G.I. Joe, swapped their innards and replaced the dolls on the shelves. The result: the altered Barbie now barks, “Eat lead, Cobra!” while Joe chirps, “Let’s go shopping!” And last year’s talking Barbie, whose complaint that “math class is hard” caused a very negative response from parents and educators, had to be recalled for an attitude adjustment.

Talking dolls themselves aren’t all that’s been making Barbie news. The book Mondo Barbie (St. Martin’s Press), an anthology of short stories and poems printed on bright pink pages, arrived at the LILITH office some months ago, with a memo from its publicist confessing that “My name is Lynn, and I owned a Barbie.” A leitmotif of the book is biting Barbie’s pointy, chewy little plastic feet.

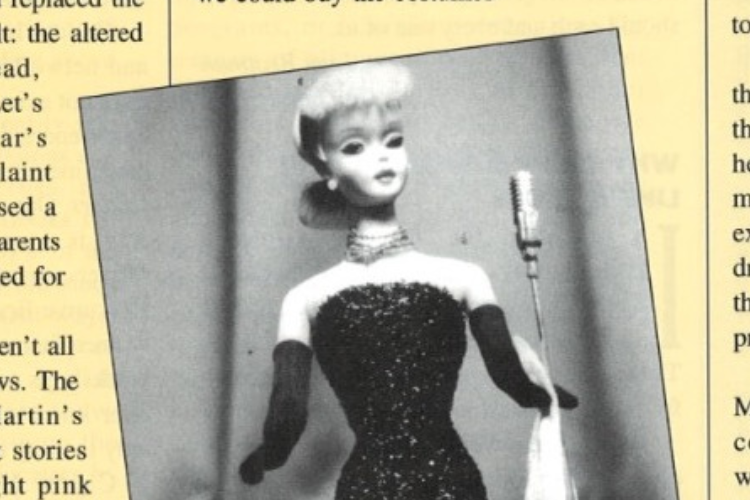

LILITH decided, in the wake of all this Barbie news, to explore Barbie’s origins with her mom—Ruth Handler of Los Angeles, a founder of Mattel toys in 1944, and the creator of the Barbie and Ken dolls in the late 1950’s.

“The dolls are named for my own children. Barbie and Ken,” Hendler said in a telephone interview.

“Barbie used to love to play with paper dolls. We went to the dime store together each Saturday, and I noticed that she always chose teenage dolls, never baby dolls or children dolls, and she and her friends used to play for hours with the teenage dolls. I listened to how they would project their future with their dolls.”

The idea of a doll with breasts was not received well. Most of the buyers [for stores] were men, and some didn’t think women would want their daughters to have a doll with breasts!

“Finally, when Barbara was too old to play with dolls—12 or 13—we took the children to Europe. We were walking down a street in Lucerne and in the window of a toy store was a display of grown-up dolls with women’s bodies. They were called ‘Lilly’ from a European cartoon, and were wearing ski outfits. There were 4 or 5 different styles of ski outfits. I asked Barbara, ‘Would you like one for your room—decoratively?’ She had a hard time choosing which one she wanted. I asked if we could buy the costumes separately and I got a ‘crazy American’ reaction.

“In Vienna it was the same story with the Lilly doll—with a new ski outfit we hadn’t seen in Switzerland. So I bought it for myself.

“Barbara never did get the dolls! I took them to use as models for our people, to show what I meant by an adult teenage doll. The idea of a doll with breasts was not received well. Most of the buyers [for stores] were men, and some didn’t think women would want their daughters to have a doll with breasts! And they themselves didn’t want their daughters to have such a doll! But when we first shipped the doll it just walked off the shelves.”

And what were parents’ initial reactions to a doll with breasts?

“Parental politics never got in the way of their choices,” says Hendler. “A mother saw the play pattern the doll could provide for her daughter. It provides for millions and millions of little girls an important play experience; it gives a little girl the ability to dream about her future. A girl can interpret the adult world around her with this doll as a prop.”

Hendler and her husband ultimately sold Mattel, and in 1976 she started Nearly Me, a company making artificial breasts for women with breast cancer. (“My life seems to be a series of going from breast to breast,” she observes wryly.) “As soon as the women buyers for Nearly Me found out that I had created Barbie they raved. It surprised me. Barbie had a very very strong place in their growing up years.

What about the objections of many feminists that Barbie presents too idealized and unrealistic an image of women’s bodies—long, long legs, a shortened torso, feet forever pointed for high heeled shoes?

“When we first brought out Barbie I was very much against her being too pretty or having a distinctive personality. I understood the need of little girls to project themselves into their dreams. About feminist criticism: I don’t even respond to that. The fact that Barbie is so loved speaks for itself.”